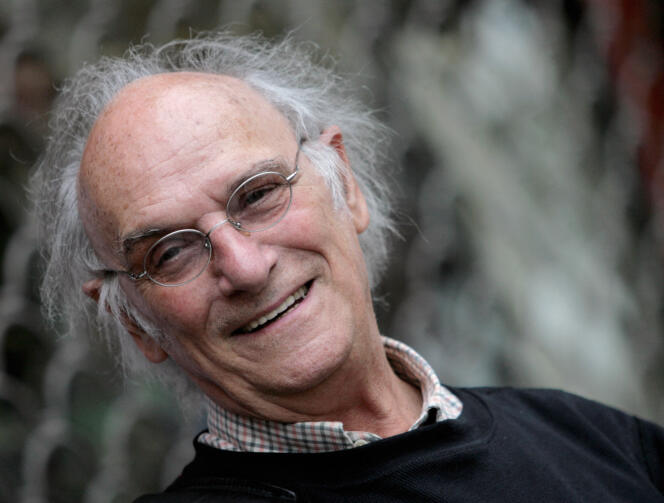

Acclaimed Spanish director Carlos Saura, who died on Friday, February 10, hit the global spotlight in the 1960s with critiques of Franco's dictatorship, later focusing on films about music and dance, notably flamenco.

Often referred to as a giant of Spanish cinema alongside Luis Bunuel and Pedro Almodovar, Saura made about 50 films over a career spanning five decades. And he earned a host of awards.

"His political commitment, his sense of aesthetics and his artistic culture make Carlos Saura a major figure of European cinema," French daily Le Figaro wrote in a biography on its website.

Fooling Franco's censors

Saura was born on January 4, 1932, in the northeastern town of Huesca to a family of artists: His mother was a pianist and his brother, Antonio, would become a well-known painter. In his youth, he developed a love of photography before following cinema studies.

He first won international recognition with The Hunt (1966), his critique of the regime of dictator Francisco Franco which won the Silver Bear, the second-highest award at the Berlin Film Festival.

He then went on to direct Peppermint Frappe (1967), a study of Spain's middle-class being caught between the past and present, which earned him the same award in Berlin the following year.

To get round the regime's censorship, Saura used metaphors and symbolism, attacking pillars of the dictatorship such as the church, the army and family in films such as The Garden of Delights (1970) and Ana and the Wolves (1972).

His 1975 film Cria Cuervos (Raise Ravens) – about a little girl who survives stifling circumstances, similar to a dictatorship, by inventing a fantasy world – won the Cannes Film Festival's Jury Prize in 1976, which he had previously won with his 1974 drama Cousin Angelica.

His films often touch on themes of memory and death, including Mama Turns 100 (1979), a hard-hitting tale about the neuroses of the post-Franco society, nominated for best foreign film at the 1980 Oscars.

He won the Berlin Film Festival's top prize, the Golden Bear, for Deprisa, deprisa (Faster, Faster), a 1981 film about juvenile delinquents.

"In many of his films... he creates sophisticated expressions of time and space by fusing reality with fantasy, past with present, and memory with hallucination," according to a 2003 synopsis of interviews by Linda M. Willem.

Flamenco trilogy

After Franco's death in 1975 and Spain's transition towards democracy, Saura shifted focus to his love of music and dance with productions focused on tango, Argentinian folklore, opera and above all flamenco.

He is best known for his 1980s trilogy of flamenco films Blood Wedding, Carmen and A Love Bewitched. He followed in the 1990s with Sevillana, Flamenco and Tango, the latter nominated for the best foreign language Oscar in 1999.

In 2002 he cast celebrated Spanish dancer Aida Gomez in the ballet Salome and in 2009 made a historic adaptation of I, Don Giovanni.

Saura also worked as a photographer throughout his life, collaborating with specialist magazines and participating in numerous exhibitions.

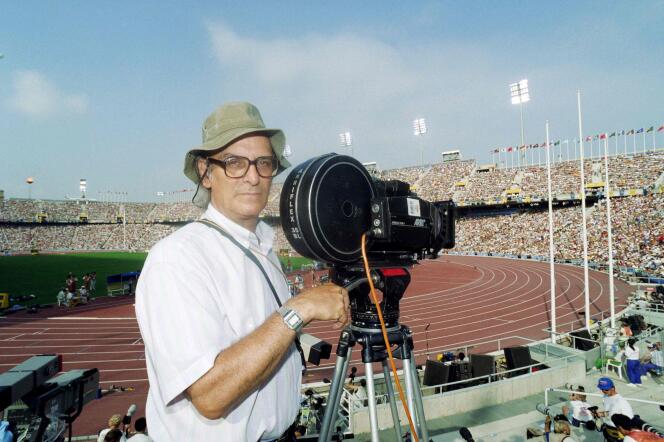

He had a long-running relationship with actress Geraldine Chaplin, Charlie Chaplin's daughter, with whom he made nine films and had one child. He also married several other women. Saura also directed the official film for the Barcelona Olympics in 1992 Marathon.