Haze over the Valley, by Robert Bevan, c. 1913. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

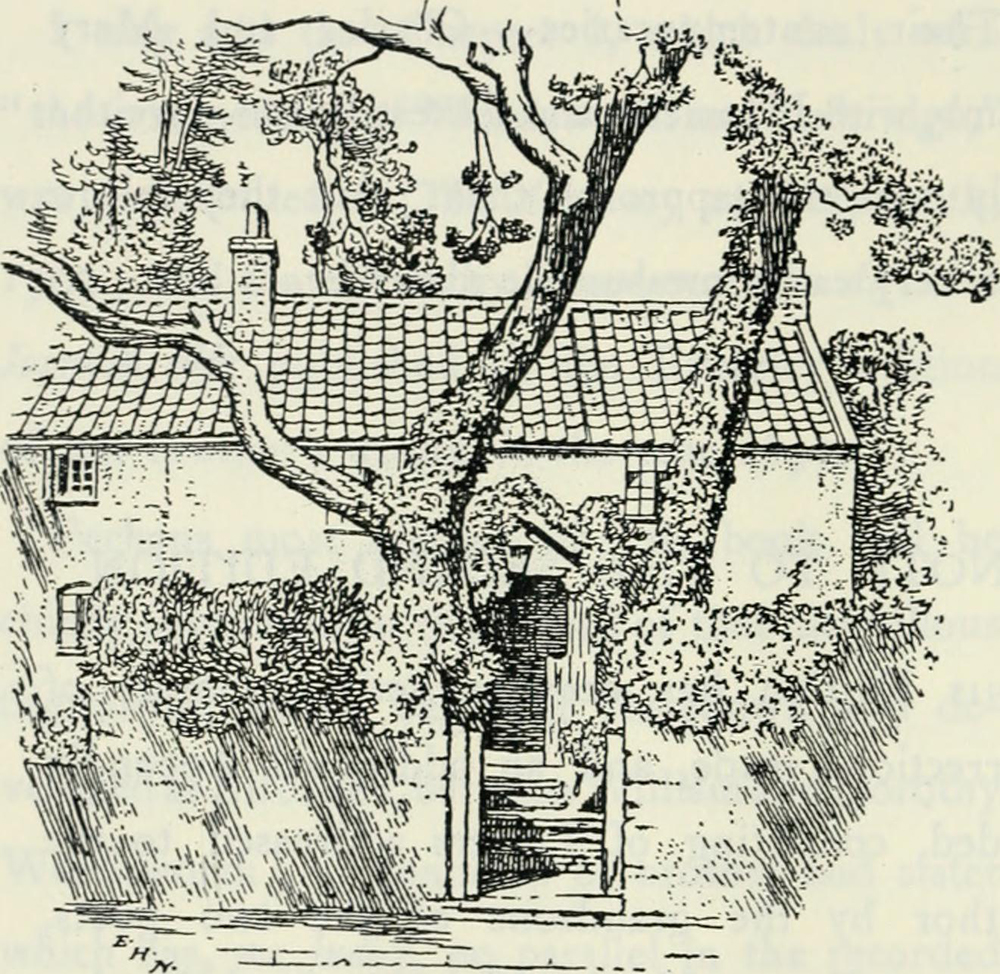

On an early June afternoon in 1797 Samuel Taylor Coleridge came down the road to Racedown Lodge from Crewkerne, crossing the county line from Somerset into Dorset. He cut a corner by leaping over a gate and bounding across a field. The gateway is still there, though the gate is now of metal. The field slopes down into the wooded valley. Looking to the right as you make for the handsome, tall square-fronted house of red brick, you see the hill on the far side of the valley and imagine the prospect of walks in the lush pastures and fresh air.

William Wordsworth would never forget this moment. The collaboration was about to begin. He immediately read “The Ruined Cottage” to his new friend. After tea, Coleridge read out two and a half acts of a play he was working on called Osorio. Wordsworth responded the next morning with a reading of The Borderers. Coleridge would stay until the end of the month. Half a century later, his children Sara and Derwent would call this year of shared creativity the annus mirabilis.

Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy was delighted with their house guest. She described him in a letter to her future sister-in-law Mary Hutchinson:

You had a great loss in not seeing Coleridge. He is a wonderful man. His conversation teems with soul, mind, and spirit. Then he is so benevolent, so good-tempered and cheerful, and like William interests himself so much about every little trifle. At first I thought him very plain, that is for about three minutes. He is pale and thin, has a wide mouth, thick lips, and not very good teeth, longish loose-growing half-curling rough black hair. But if you hear him speak for five minutes, you think no more of them. His eye is large and full, not dark but gray…it speaks every emotion of his animated mind. It has more of “the poet’s eye in a fine frenzy rolling” than I ever witnessed. He has fine dark eyebrows, and an overhanging forehead.

They decided that they had to live closer together. In order to make arrangements, Coleridge returned to the little cottage in the Somerset village of Nether Stowey that he rented from Tom Poole, a wealthy tanner by trade, a political radical by inclination, and a lover of poetry. A few days later, Coleridge was back at Racedown, ready to bring William and Dorothy to his home.

Coleridge loved company. “I shall have six companions,” he had written upon making the move to Nether Stowey at the beginning of the year. He identified the six as Sara, his wife; Hartley, his baby; his “own shaping and disquisitive mind”; his books; his “beloved friend Thomas Poole”; and “lastly, Nature looking at me with a thousand looks of beauty, and speaking to me in a thousand melodies of Love.”

They loved the area: “There is everything here,” wrote Dorothy to Mary Hutchinson, “sea, woods wild as fancy ever painted, brooks clear and pebbly as in Cumberland, villages so romantic.” Brother and sister wandered out and found “a sequestered waterfall in a dell formed by steep hills covered with full-grown timber trees.” The whole place had “the character of the less grand parts of the neighborhood of the Lakes.” Walking in the rolling Quantock hills above the village, they spotted a fine house called Alfoxden in the nearby village of Holford. They discovered that it was available to let. Within a week, Wordsworth had signed a one-year lease, and a week after that they moved.

Coleridge’s cottage was proving far too small to house them all, especially as Charles Lamb had now come to stay. He was wonderful company: tiny in stature, bowlegged, stammering, warm, witty, and able to laugh even at his own history of mental illness. The year before, he had written to Coleridge:

I know not what suffering scenes you have gone through at Bristol—my life has been somewhat diversified of late. The six weeks that finished last year and began this your very humble servant spent very agreeably in a madhouse at Hoxton. I am got somewhat rational now, and don’t bite any one. But mad I was—and many a vagary my imagination played with me, enough to make a volume if all told.

His visit to Nether Stowey was respite from the trauma of the previous autumn, when, in a fit of madness, his sister Mary had stabbed their mother to death with a kitchen knife during a row about the treatment of a serving girl. Mary was being held in a lunatic asylum, from which she would subsequently be released on condition that Charles watched over her. They became the closest of companions, writing stories together, including their Tales from Shakespeare, novelistic retellings of the comedies and tragedies that introduced generations of children to the plays.

It was perhaps due to the sheer number of bodies in the tiny cottage, which can still be visited today, that Sara Coleridge accidentally spilt a skillet of boiling milk on her husband’s foot. This confined him to the cottage and its garden, depriving him of walks across the hills in the company of William, Dorothy, and Charles. Instead, sitting in a lime-tree bower, he followed them in imagination, flexing his poetic muscles in the easeful conversational style of blank verse that he and Wordsworth would perfect over the ensuing months:

Well, they are gone, and here must I remain,

This lime-tree bower my prison! I have lost

Such beauties and such feelings, as had been

Most sweet to have remember’d, even when age

Had dimm’d my eyes to blindness! They, meanwhile,

My friends, whom I may never meet again,

On springy heath along the hilltop edge

Wander in gladness, and wind down, perchance,

To that still roaring dell, of which I told…

…Now my friends emerge

Beneath the wide wide Heaven, and view again

The many-steepled track magnificent

Of hilly fields and meadows, and the sea

With some fair bark perhaps which lightly touches

The slip of smooth clear blue betwixt two isles

Of purple shadow! Yes! They wander on

In gladness all.

The gentle Quantock landscape was evoked by Dorothy in vivid prose in another of her letters to Mary Hutchinson, in which she also described Alfoxden House. It was a large mansion with enough furniture for a dozen families. The parlor that would soon become their favorite room faced a garden that was well stocked with vegetables and fruit. There was a courtyard in front, with a grass plot, gravel walks, shrubs, and moss roses in full bloom. The house looked out on a hill covered with trees and ferns, deer and sheep moving among them. They could glimpse the sea—the Bristol Channel—across the countryside of woodland and meadow. They strolled in the nearby woods, listening to the waterfall in the glen, and then they would take off, walking for miles across the smooth-topped hills.

Dorothy had a remarkable sense of color. January 21: “Walked on the hilltops—a warm day. Sat under the firs in the park. The tips of the beeches of a brown-red, or crimson. Those oaks, fanned by the sea breeze, thick with feathery sea-green moss, as a grove not stripped of its leaves. Moss cups more proper than acorns for fairy goblets.” She also had a constantly inquiring mind. January 22: “The day cold—a warm shelter in the hollies, capriciously bearing berries. Query: Are the male and female flowers on separate trees?”

Each day’s entry is a thing of wonder, a window onto a life of unity between the little group of companions and their natural environment:

February 3rd. A mild morning, the windows open at breakfast, the redbreasts singing in the garden. Walked with Coleridge over the hills. The sea at first obscured by vapor; that vapor afterward slid in one mighty mass along the seashore; the islands and one point of land clear beyond it. The distant country (which was purple in the clear dull air), overhung by straggling clouds that sailed over it, appeared like the darker clouds, which are often seen at a great distance apparently, motionless, while the nearer ones pass quickly over them, driven by the lower winds. I never saw such a union of earth, sky, and sea. The clouds beneath our feet spread themselves to the water, and the clouds of the sky almost joined them. Gathered sticks in the wood; a perfect stillness.

Dorothy sees the union of earth, sky, and sea, noting in prose. Wordsworth reflects upon it, philosophizing in verse.

Walking over to Tom Poole’s house after tea one day, they noticed, in Dorothy’s words,

The sky spread over with one continuous cloud, whitened by the light of the moon, which, though her dim shape was seen, did not throw forth so strong a light as to checker the earth with shadows. At once the clouds seemed to cleave asunder, and left her in the center of a black-blue vault. She sailed along, followed by multitudes of stars, small, and bright, and sharp.

William turned this observation into verse, first copying and expanding the language:

The sky is overcast

With a continuous cloud of texture close,

Heavy and wan, all whitened by the Moon,

Which through that veil is indistinctly seen,

A dull, contracted circle, yielding light

So feebly spread, that not a shadow falls,

Checkering the ground…

He then introduces a human figure: a lonesome traveler who sees above his head "The clear Moon, and the glory of the heavens.” With this, he reverts to Dorothy’s words:

There, in a black-blue vault she sails along,

Followed by multitudes of stars…small

And sharp, and bright.

Coleridge perceived that Dorothy’s eye and William’s mind worked in perfect harmony. He was deeply impressed by her ardent and impressive manners, “Her information various. Her eye watchful in minutest observation of nature; and her taste a perfect electrometer. It bends, protrudes, and draws in, at subtlest beauties and most recondite faults.” Some time later, writing of himself and her and William, he said, “Though we were three persons, it was but one God.” Coming from Coleridge the religious Unitarian, this trinitarian image could be read two ways: Did he mean that they were a creative Trinity, three-in-one and one-in-three, or, more negatively, that their creativity was triune but the credit was taken entirely by the godlike William?

It is impossible—and perhaps undesirable—to disentangle the shared creativity. From a modern feminist point of view, Dorothy looks like the silenced partner. Yet she shied away from the possibility of becoming a published author, and she never complained about William using her journals as raw materials for his poems. It is possible indeed that some of the images she wrote down after their daily walks were originally William’s, spoken as they looked and listened and shared their impressions. Intriguingly, those exquisite four first sentences in the diary entry for January 20, 1798, appear not only in the posthumously published text of Dorothy’s now lost journal, but also in William’s hand in his Alfoxden notebook, where they are scribbled fluently in a way that suggests a first draft rather than a painstaking secondary copy.

In The Prelude, Wordsworth acknowledges the twin inspiration of Coleridge and Dorothy. Indeed, in recalling the passage of his life when disillusionment with the French Revolution set in and the idea of a poetic revolution took its place, he gave many more lines of credit to his sister than to his friend. Coleridge lends a hand in regulating his soul, but Dorothy does far more:

Ah! then it was

That Thou, most precious Friend! about this time

First known to me, didst lend a living help

To regulate my soul, and then it was,

That the beloved Woman, in whose sight

Those days were pass’d, now speaking in a voice

Of sudden admonition like a brook

That does but cross a lonely road, and now

Seen, heard, and felt, and caught at every turn,

Companion never lost through many a league,

Maintain’d for me a saving intercourse

With my true self: for, though impair’d and changed,

Much, as it seem’d, I was no further changed

Than as a clouded, not a waning moon.

She in the midst of all preserv’d me still

A Poet, made me seek beneath that name

My office upon earth, and nowhere else,

And lastly, Nature’s self, by human love

Assisted, through the weary labyrinth

Conducted me again to open day,

Revived the feelings of my earlier life,

Gave me that strength, and knowledge full of peace,

Enlarged, and never more to be disturb’d,

Which through the steps of our degeneracy,

All degradation of this age, hath still

Upheld me, and upholds me at this day.

As they walked the deserted tracks along the top of the Quantocks, Coleridge may have been the one to come up with the idea of writing a long poem that twisted and flowed like a brook, but it was Dorothy who offered “sudden admonition like a brook / That does but cross a lonely road” and in so doing returned her brother to his “true self,” guiding him on his path to his true vocation as a poet responsive to “Nature’s self.” It was his sister who spurred him to revive “the feelings” of his “earlier life.”

Excerpted from Radical Wordsworth: The Poet Who Changed the World by Jonathan Bate, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 Jonathan Bate. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.