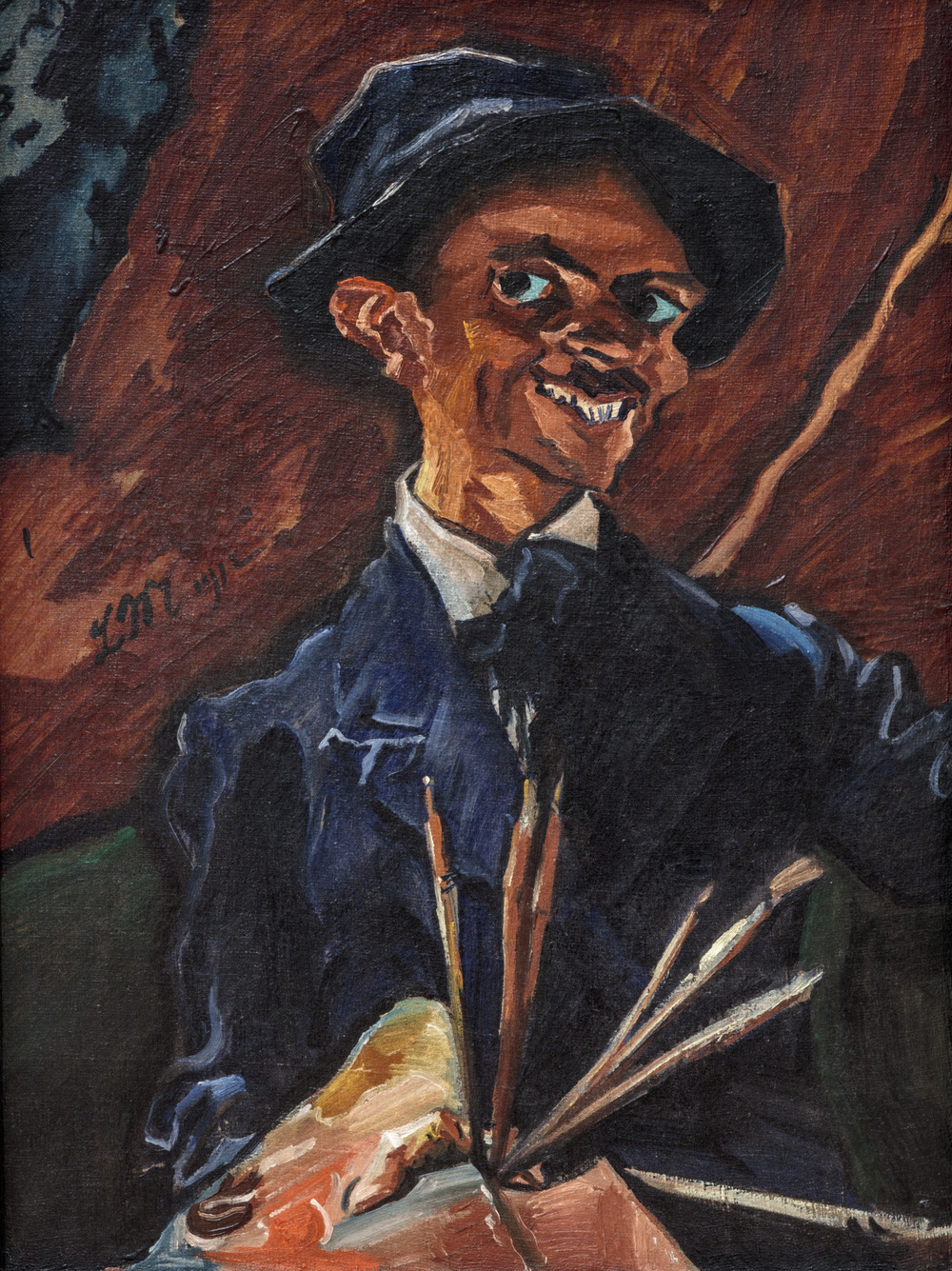

Ludwig Meidner, Selbstbildnis (Self-Portrait), 1912

Anne Popiel

Editor and translator, Potsdam Graduate School of the University of Potsdam, Germany

PhD in Germanic languages and literatures, Washington University in St. Louis

Painted in the same year that he cofounded the artists’ group Die Pathetiker,1 named for those of passionate temperament, Ludwig Meidner’s Selbstbildnis (Self-Portrait) reveals a complex dialogue between the painter’s individualism and the urban environment of Berlin at the height of German Expressionism. Beginning with a rejection of classical and realist doctrines, Expressionist painters like the Pathetiker artists “shared a common determination to subordinate form and nature to emotional and visionary experience.”2 Further, the manipulation of form to reflect emotional conditions, or the pathos of the individual, can be seen as the attempt of “the individual to preserve the autonomy and individuality of his existence in the face of overwhelming social forces,” which Georg Simmel, a prominent Berlin sociologist, examined in his 1903 study “The Metropolis and Mental Life.”3 Simmel reflected on the modern city’s impersonality, or “hypertrophy of objective culture,” which stifles the uniqueness of the individual. The desire to exaggerate the personal element, as he noted, often incorporated a larger utopian goal of improving the world in a time of growing discontent in the face of Germany’s burgeoning materialism, industrialization, and urbanization.4 In addition, revolutionary upheavals in religious, scientific, and moral thinking, such as Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–85), Freud’s dream theory (1900), and Einstein’s theory of relativity (1905), for example, challenged traditional cultural foundations and paradigms of thought, while a number of political crises leading up to World War I exacerbated the general sense of social anxiety.5

In the destabilized and tumultuous environment of prewar Berlin, Meidner, like his fellow Expressionists, both exalted in the city’s dynamism and was repulsed by its corruption. He chose to turn inward, giving primacy to emotional states over material depictions in an extensive series of self-portraits, to which this example belongs. Not simply a realistic representation of his physical appearance and surroundings, Meidner’s self-portrait synthesizes his emotions, body, and environment. His expressive strokes evoke an identity of a tormented and isolated artist while at the same time conveying a connection to, as well as a dependence on, the very culture that he mocks and rejects.

In his 1914 instructional essay published in the journal Kunst und Künstler, translated as “An Introduction to Painting Big Cities,” Meidner explained the close connection between the modern urban environment and his painting practice, expressing the need for “a deeper insight into reality” through a more intense seeing. According to Meidner, a painter should no longer attempt merely to represent exactly the sights, sounds, and movement of the metropolis but must organize the multitude of sensual impressions of the city into a new composition, one that expresses more than a simple mirroring of images. “A street isn’t made out of tonal values,” Meidner wrote, “but is a bombardment of whizzing rows of windows, of screeching lights between vehicles of all kinds and a thousand jumping spheres, scraps of human beings, advertising signs, and shapeless colors.” The painter must absorb the urban bustle, the escalating technologies, “the roaring colors of buses and express locomotives, the rushing telephone wires” and, Meidner instructed, must paint “brutal[ly] and unashamed[ly],” for “your subject is also brutal and without shame.” The dynamism of the city, both the “glorious” and the “grotesque,” the “elegance of iron suspension bridges” and the “confused jumble of buildings,” must penetrate the painter’s sensitivities and be integrated into the final depiction in a vibrant and forceful manner.6 As a prime example of this, one may see that the tension of conflicting negative and positive energies of the flurry of urban activity, as well as of the city’s cultural upheaval, are expressed with the required pathos in his Self-Portrait. By incorporating such conflicting impressions, Meidner’s painting may well be seen as an indirect portrait of the big city itself, filtered through his own subjective experiences and projected onto a physical rendering of his “self.”

A detailed exploration of the colors, forms, and structure of his self-portrait reveals many clues that help to visualize this interplay between the individual and the environment of the modern metropolis, between the painter and the painting. Meidner’s mocking, eerie grin and piercing, skewed stare accost the viewer first. The contours of his face are exaggerated, bold; jerky twists of the brush express something disquieting in the arch of his brow. The unsteady application of paint seems to embody an anxious state of mind. Indeed, the result is a rather negative alteration, and despite Meidner’s later denunciation of such self-projection as self-worship,7 the portrait does not seem to flatter him at all. The connection between self and surroundings is further extended to the browns and midnight blues of his body, which are repeated in the colors of the background, while the expressive, chaotic brushwork of his skin and clothing echoes almost exactly the unstable shapes and irregular color fields behind the figure. The jagged shapes might be seen as Meidner’s interpretation of the city’s right-angled architecture: “We see beauty in straight lines and geometric forms,” he wrote. “Don’t be fooled. A straight line is not cold and static! You need only draw it with real feeling. . . . It can be first thin and then thicker and filled with a gentle, nervous quivering.”8 In this repetition of background and foreground, Meidner’s receptive response to his surroundings is made visible: the colors and shapes of the background seem to have penetrated and altered the figure in the foreground.

Further signifying the importance of the individual artist’s sensory and emotional receptivity to the environment, the most intensely colored parts of Meidner’s body are also the most exposed: the neck, highlighted in the brightest yellow; his right ear, standing out in a streak of red; the eyes, which glow blue. These body parts, almost vibrating in flashes of color, appear the most receptive to the constant motion, noise, and vitality of Berlin’s metropolis, which is evoked in the painting’s background as an interior space distorted by a disorienting sweep of diagonals. Indeed the diagonal line in the background on the right-hand side heightens the tension in the work as it jabs into the painted figure’s shoulder, pulsing unsteadily with the diagonal lines of the thick colors of his neck and the brushes he holds in his hand. The nervous, shaky geometry conveys an anxious feeling, one that culminates in a sense of the threat of impending social or mental collapse.9

Dressed thus almost in camouflage and armed with palette and brushes, like a shield and so many spears, Meidner’s self-image is presented as if ready to fight in the urban cityscapes he called “battlefields.”10 In describing the urban battlefield, he frequently referenced dynamic lines that “rush past us on all sides,” as well as “many-pointed shapes” that “stab at us.”8 His use of violent and inflammatory imagery, in both textual and painterly contexts, complemented the sentiment at a time when many Expressionist artists and thinkers looked forward to the upcoming war as an opportunity for revolution and a new beginning, a throwing-off of the old authoritarian Wilhelmine Empire.12 The old regime was associated with the dominant culture of the bourgeoisie, a social class to which Meidner makes indirect and sardonic references in several of his writings, implying an embrace of his own working-class culture and a condemnation of the higher class. Indeed, in the painting he wears the suit and hat most typical of the bourgeoisie, yet his vicious grin suggests a mockery and rejection of that very same society.13

In this complex relationship to his environment, Meidner seems both to defend his subjective autonomy and to glorify the power of the very culture that threatens him as an individual. In the end, by distorting the forms of objective reality to reflect an emotional state, he can be seen as reacting to the complex social forces of the metropolis that Simmel described. This results in a painting that exudes a palpable sense of anxiety, eliciting from the viewer the state of emotional and sensory perceptivity that the painting embodies. Just as Meidner’s self-portrait presents a mirror image, however much distorted, of the painter looking at himself, saturated by the vibrancy and chaos of the modern times around him, so too may it bring us as viewers around to ourselves, drawing our attention to the (discomfiting) moment of our own time and place and transforming us, in a way, into the portrait’s mirror image.

- 1 Along with Meidner, the group consisted of Richard Janthur and Jakob Steinhardt. See Rose-Carol Washton Long, German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism (New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1993), 101.

- 2 Victor H. Miesel, Voices of German Expressionism (London: Tate Publishing, 2003), 1.

- 3 Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), excerpted in Art in Theory, 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992), 130.

- 4 Ibid., esp. 130, 135.

- 5 See Miesel, Voices of German Expressionism, 6.

- 6 Ludwig Meidner, “Das neue Programm: Einleitung zum Malen von Großstadtbildern,” originally published in Kunst und Künstler 12 (1914): 312–14; reprinted in Miesel, Voices of German Expressionism, 110–15.

- 7 See “Heiteres Zwiegespräch über Porträtmalerei, hauptsächlich das Selbstporträt, zwischen Ludwig Meidner und Rudolf Grossmann,” in Verteidigung des Rollmopses: Gesammelte Feuilletons 1927–1932, ed. Michael Assmann (Frankfurt am Main: Schöffling, 2003), 206–7.

- 8 Meidner, “An Introduction to Painting Big Cities,” in Miesel, Voices of German Expressionism, 113.

- 9 See Peter Vergo, Twentieth-Century German Painting (London: Sotheby’s Publications, 1992), 270.

- 10 “Are not our big-city landscapes all battlefields filled with geometric shapes?” Meidner, cited ibid.

- 11 Meidner, “An Introduction to Painting Big Cities,” in Miesel, Voices of German Expressionism, 113.

- 12 See Long, German Expressionism, 77.

- 13 This notion was suggested by Claudia Marquart in “Die früherenSelbstbildnissen 1905–1925,” in Ludwig Meidner: Zeichner, Maler, Literat 1884–1966, ed. Gerda Breuer and Ines Wagemann (Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje, 1991), vol. 1, 31. For a darkly humorous example of Meidner’s references to the bourgeoisie, see his “Verteidigung des Rollmopses,” in Assmann, Verteidigung des Rollmopses, 150–58.