William Robinson

William Robinson

Recent Paintings

Savode Gallery

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 1997

Review by Grafico Topico's SUE SMITH

An edited version of this review was published in TheCourier-Mail 1997

William Robinson, back in Brisbane with a marvellous exhibition after an absence of nine years, considers himself a lucky man

William Robinson, back in Brisbane with a marvellous exhibition after an absence of nine years, considers himself a lucky man

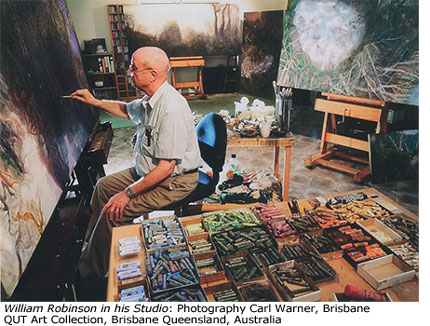

For most of his career he has worked productively in quiet obscurity, safely quarantined from the distractions of media hype and art world razzamattaz. He had moderately successful exhibitions in Brisbane in the 1960s and '70s, taught for a living at the Brisbane CAE (now QUT) until 1989, and lived quietly -- making witty, original paintings of life on the farm with his wife Shirley and family at rural hamlets at Birkdale, then at Beechmont, near south-east Queensland's Lamington National Park.

Then suddenly in the late 1980s, when Robinson was in his 50s, bald and plump, and but for a mischievous twinkle in his intelligent eye, easily mistaken by a drongo southern press as a kind of hayseed naif, Pa Kettle with a paintbrush, he emerged as a very considerable painter and an overnight media sensation.

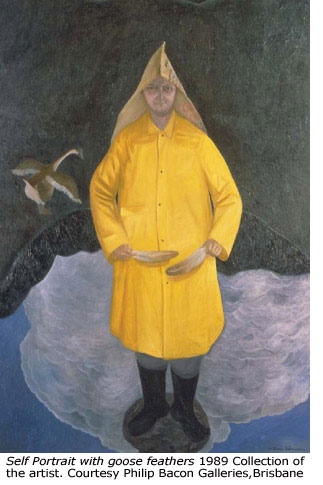

It was firstly Robinson's Archibald Prize winning self-portraits (two have won, and another came close to taking the coveted award) that set an astonished art world a-flutter. In these, he gently, but oh so acutely, pricked the inflated balloon of pomposity, flash Sydney social climbing and shrill self-congratulation that makes this paltry-paid prize for a dinosaur art genre such a silly, but unmissable, annual event. In images which challenged portrait tradition and sometimes upset critical sensibilities, he painted himself once as an unlikely farmer-warrior trotting on a fat horse, another time in his pyjamas, and like Hogarth's shrimp girl - or rather, more like John Cleese in the fish-slapping dance - holding stunned mullet in both hands.

These were all great fun, and, in terms of painting quality, very good pictures, but for Robinson amounted to no more than a bit of light relief, a yearly diversion from more serious artistic matters.

These were all great fun, and, in terms of painting quality, very good pictures, but for Robinson amounted to no more than a bit of light relief, a yearly diversion from more serious artistic matters.

It is for his landscapes that Robinson ultimately will be remembered: as an artist who has had a significant statement to make and a significant self and interior vision to express. Whereas many Australian painters have nothing much to say, and too often are cruelly feted and ruined by a fickle art world while young and immature, becoming bright flames that soon sputter out, Robinson fortunately has been left alone, and now at 61 is painting the best pictures of his life. He divides his time these days between his studios at Kingscliff near the Tweed River, and at Springbrook on the edge of the Springbrook National Park.

Many viewers will recognise - but will wonder anew at - the Springbrook rainforest scenes which are depicted in his latest show at Brisbane's Savode Gallery - a dozen large canvases and a huge three-part work, `Creation landscape: Land and Sea' which won the Wynne Prize for landscape. In these rainforest paintings, Robinson is governed by so intense and visionary an imagination that his admirers see him as a romantic painter on a par with John Constable and Caspar David Friedrich.

What is different for Robinson, however, is that he is inventing a new painting language for a lost, primeval landscape that the rest of the world hardly knows. The questions he has asked himself are how to do justice, in a fresh and inventive way, to this 20-million-year-old vista of mist-covered volcanic ranges, where a hundred waterfalls plunge down gorges to pristine valleys densely filled with 2000-year-old Antarctic beeches, eucalypts, ferns and mosses? -- and how to capture the feelings of the human spirit, awed and uplifted by the scene? Robinson manages to do this by unshackling us from ordinary perceptions of space and time.

He encloses the viewer in an immense, revolving, vertigo-inducing space: locating us as if we were flying or free-falling from the loftiest heights of a mountain rim, but as if we were also looking up from the bottom of the valley below at the same time. Freed from the tethers of land and gravity, in these pictures we may also disregard the dictates of time, as we watch the movement of night and day, sun and moon, storm and rainbow across the scene.

There is darkness in the pictures, too, natural cataclysms analogous to human strife and suffering, but always the viewer eventually moves into light. As Robinson himself says, these are pictures of hope, of the healing balm of nature to a troubled humanity. In the art scene today, so often dominated by musings on urban blight, hopelessness and despair, Robinson offers an uplifting alternative.

Copyright © 1997 Sue Smith. Not to be used without the permission of the author

Suggested Reading: