What do you think?

Rate this book

391 pages, Hardcover

First published September 23, 2005

He had no interest in anarchist politics or, indeed, politics of any sort; he was unlikely to be persuaded into a genuine anarchist act of random and meaningless violence. Munch was fond of debating many existential questions, but he could see little point in the central question posed by the doctrine of nihilism; ‘What should we be doing if the whole of existence is absurd?’ For Munch the answer was obvious, ‘Painting, of course.’ To the artist fell the duty of tearing off the mask of modern man to show his true face. The question remained as always – how? It was this ‘how’ that fuelled the fires of discussion. (p. 112).

Munch read a great deal. Although close to some leading minds of the time in the fields of literature, philosophy, music, medicine and that emerging art, psychiatry, he never accepted verbal exchanges as unconditionally as he accepted the written word. As a result, books played a large part in influencing his thought and his pictures. An important part of writing this book has been that if I knew what Munch was reading at a given time in his life, I would read the same book while writing about that period. (p. 6).

Through his experience of looking at second-rate paintings Edvard had discovered how much he hated the carefully detailed picture, in which every [centimeter] is brought up to the same standard of finish and then covered by the golden glow of Academy varnish smeared over it like melted butter. He hated the painted passage reduced to uniformity of texture, the brushstrokes smoothed into pretending they were made by a machine, and he hated the slick finish that stopped the eye at the surface, holding the spectator at arm's length. It was now that he made an observation that would be a driving principle of his art: ‘There must be no more pictures covered in brown sauce’, he wrote, resolving to take a new and truthful road. (p. 64).

Throughout Edvard's life, Dostoevsky was the writer of greatest importance to him; indeed, his last action on his last day on earth was to lay aside the Dostoevsky novel he was reading before composing himself for death. But while father and son each found deep and personal meanings in the same texts, they read them through different prisms. Christian read them as faith-affirming Christian texts; Edvard as psychological dramas, as the novels of a modern writer who, as the narrative unfolded, succeeded in conveying in parallel the outer and the inner life. This was exactly what Edvard wanted to achieve with paint. ‘Just as Leonardo da Vinci studied human anatomy and dissected corpses, so I was trying to dissect souls.’... ‘No one in art,’ he told a friend, ‘has yet penetrated as far [as Dostoevsky] into the mystical realms of the soul, towards the metaphysical, the subconscious, viewing the external reality of the world as merely a sign, a symbol of the spiritual and metaphysical.’ (p. 74).

Then ‘all sensations are perceived by all senses at once. My own impression is that I am breathing sounds and hearing [colors], that scents produce a sensation of lightness or of weight, roughness or smoothness, as if I were touching them with my fingers.’ The symptoms of absinthe poisoning are heavy sweating, hallucinations, sleeplessness and a sense of hideous oppression. (p. 158).

The period is full of artists like Proust driven by revelations. Proust's four critical memories in A la Recherche du temps perdu were stirred by small physical events such as the feel of a napkin on his lips at a party that recalled the roughness of a towel after a swim at Balbec and, of course, the famous Madeleine moment. (p. 159).

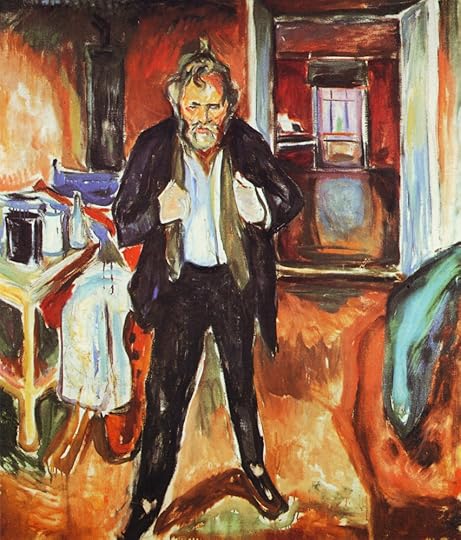

…he was finding himself pathologically unable to part with his paintings, his ‘children’. When he sold them, he found himself missing them dreadfully and would often try to ‘borrow them back,’ a request that did not always meet with enthusiasm. He did not regain possession to hang them up ostentatiously, or even to spend time looking at them. He just liked to know they were there, though he abused them terribly, stacking them up against the walls of the chaotic studios and walking into them or spilling drinks on them. He might fly at them in a rage, kick them, tear them apart. One friend describes how Munch asked him to take a picture up to the attic. ‘That damn picture gets on my nerves … it keeps getting worse and worse. Do me the [favor] of taking it up to the attic. Just toss it in there – as far as possible.’ The friend came downstairs to report failure; the attic door was jammed. Munch dashed upstairs to open the door and flung the picture into the darkness. ‘It's an evil child – I've tried everything but it resists my efforts. Believe me, that picture, if I hadn't locked it in there – would have been capable of jumping down from the hallway and hitting me in the head. Really, I've got to get it out of the house – it's a terrible picture.’ (p. 231).

It was said that in no instance did Munch lack nobility or generosity, nor was he guilty of the least baseness, but he could be irascible and irritated at having to admit to the power of money, which he scorned but the lack of which so hampered his life. (p. 239).

Observations on Munch's life by contemporaries are sprinkled with anecdotes concerning the great power he exercised over women; of how invariably he fled if they came too close, when he would feel in danger of being swallowed up, but if they did not, then he felt alone and abandoned. (p. 249).

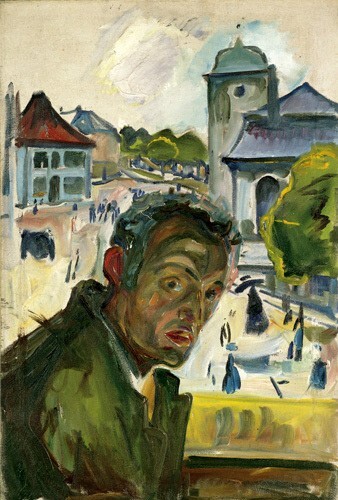

Munch's fear of open spaces and his vertigo had a great deal to do with this subjective approach. His mental terrors were the reason he would walk though landscapes with unseeing eyes, opening the camera-shutter eyelids only occasionally. Mountains made him frightened; he dared not look up in case there was a mountain looming above him and threatening to fall on him. That was why, in one of the most mountainous countries in the world, he painted the coast, whose flatness did not threaten him. (p. 262).

This was the first exhibition of The Frieze in its ‘completed’ state but it would be a mistake to imagine that this sequence of paintings comprises an immutable entity called The Frieze of Life. To imagine The Frieze as an unchanging sequence of paintings is as great a mistake as to imagine that this biography can possibly hold more than a fraction of the complex truths of Munch's life. (p. 274).

By presenting it as he did in Berlin, it made a comprehensive narrative to a receptive public. Munch's name was connected with Nietzsche, whose recent death was inspiring waves of respect, adulation and intellectual interest that would have astonished him in his lifetime. Equally, Germany had become well versed in the concept of the epic circular narrative capable of interpretation on several levels. Wagner's Ring Cycle, first performed in 1876, was now an item of intellectual furniture. (p. 277).

Some accounts say that she sat up in bed and laughed at him. We do not know which of them originally took hold of the gun in the struggle that ensued, or whose finger pulled the trigger releasing the bullet that shattered the middle finger on [Munch’s] left hand, which must have been covering the barrel of the gun. Smoke filled the room, blood poured down his hand and she did nothing to help him. (p. 287).

Once more, he found himself in the stifling claustrophobic atmosphere of a hospital where his hand was X-rayed. The recently discovered mystical rays (that had so fascinated Strindberg that he jealously claimed to have invented them himself) saw through his flesh to the truth of his body, just as his eyes saw through the layers of clothes and flesh and masks and deceptions to the inferno of emotions seething inside the skull beneath the skin. In occult terms, this X-ray photograph had the quality of the prophecy fulfilled. He had already symbolically scraped away the flesh from this very hand in the corrosive unveiling of Self-portrait with Skeleton Arm. The damage inflicted on him, however, was more than symbolic. The tension between the temporal and the timeless, the factual and the symbolic, expressed itself in his wound.

He refused [anesthetic]. (p. 288).

I saw my fingers and hand bloody and swollen like a glove. The pain caused sweat to form on my brow, I wanted to scream but the many eyes upon me forced me to clench my jaws together instead.

The flesh was cut, trimmed, pierced, sewn and the hand resembled a piece of chopped meat. After an hour and a half the doctor announced, ‘Well, I hope that will do. The hand will not stand any more.’

I was wheeled back. My working hand would heal, I hoped. The days passed. I had a fever. The pain in the mangled hand was unbearable. When the doctor made his rounds I asked,

‘Will my hand heal? Will I be able to use it again?’

‘Yes, we hope so,’ replied the doctor. (p. 289).

There were great similarities between the spiritual journeys of Munch and Nietzsche with their curiosity about the unconscious layers of perception and illusion. Both of them treated the problems of morality after the death of God as central to life, and Munch named his Mad Poet's Diary in homage to Nietzsche's associated parable of the madman: ‘God is dead, why then do people still behave as though He were alive?’ (p. 297).

Woman as temptress was another common theme. Women were something strange for Nietzsche, mystifying and, above all, tempting; if there is one persistent refrain running through his writings about them, it is that they lure men from the path of greatness and spoil and corrupt them, a sentiment Munch often expressed in his [behavior] to the women who wanted get close to him and in his own writings: ‘I have always put my art before everything else. Often I felt that Woman would stand in the way of my art. I decided at an early age never to marry.’ He would allow them to get within a certain distance, but then he would find an excuse to retire lest the price of intimacy be paid at the expense of his mistress, art. (p. 299).

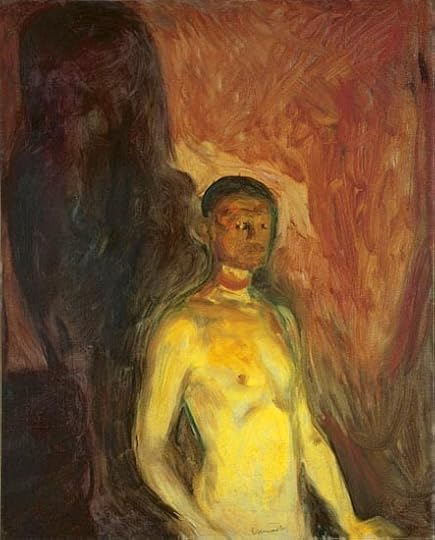

… [Munch] knew that the battle to regain sanity must include the retention of a degree of mental disturbance: I must retain my physical weaknesses; they are an integral part of me. I don't want to get rid of illness, however unsympathetically I may depict it in my art … My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My art is grounded in reflections over being different to others. My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings. (p. 323).

The writing of The Mad Poet's Diary was one bottle of pills that he took to alter the perception of his mind. Another was an exploration of the borders of visual perception and truth; not by words this time, but by means of his little Kodak camera. It was not much of an instrument: there was no [color]; every photograph was taken at the same aperture setting; every exposure probably lasted a minute; a minute to compose a statement of significance. He had long been [skeptical] of the accepted faith in the authenticity of the photograph, of the idea that it delivered ‘truth’. He saw it as an interesting instrument to be pressed into service to reveal a different way of seeing him ‘walking next to himself’ as he pressed the shutter button on the image of himself – a further exploration of how the outer related to the inner, and the contradiction between the seen and the unseen. (p. 327).

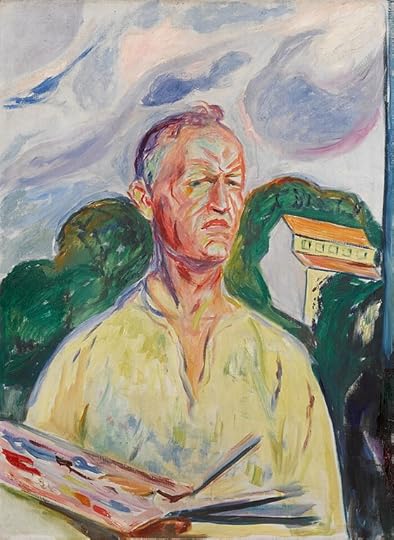

In his overcoat with his palette in one hand and the selection of his children lined up round the enclosure, he darted about putting touches to first this canvas, then that, painting them simultaneously, as a group, as he had always liked to do; the thoughts of one could flow freely through to the other in this wave-like process of creation. The outdoor studio was an enlarged version of the way he had always [disorganized] his work. There are the numerous descriptions of studios in Paris and Germany where ‘his pictures were always strewn all over the room, on the sofa, on top of the clothes-cupboard, on the chairs, on the washstand, on the stove … He often painted at night after returning home late … when one visited him in the morning, one tripped over a palette or trampled over a newly painted picture placed in such a way that it had to fall down. (p. 346).

…the director complained of some details which Munch surprisingly agreed to come and correct. The director noticed that Munch had arrived in a taxi and kept it waiting. He offered to place one of the factory cars at his disposal instead, at which Munch tossed his brush down onto the skinflint's desk, saying, ‘There, now you can ruin the rest of it yourself!’ (p. 385).