There aren't many people who've been making video games for as long as Jeff Minter. Writing his first games, like Deflex, in 1979, Minter's most recent release was this 2023's Akka Arrh, putting forty-four years of interactive media experience under his belt. If you ever feel as though video games are getting long in the tooth, consider that you can be an elder statesman in this discipline at the age of 61. While Minter spent his intern years in the industry riffing on Defender and Tempest, his modern output is just that. Its contemporary appeal is not down to him doing away with vector art and shoot-'em-up mechanics but rather internalising what a current audience expects in terms of usability and his games coming full circle to register as fashionable throwbacks.

When video games were still bouncing babies, they were chained to relatively abstract aesthetics (I'm including gameplay when I say "aesthetics") due to the restraints of primitive computers. As processors got faster and memory got chunkier, the games industry mostly saw the task of maturing the medium as one of baking more detail and narrative into games. But after every mainstream movement in an art form, there is always a rebellion: a revival of the aesthetics of old. In video games, the elastic snapped back during the mid-late 00s with the rise of neon-edged minimalism. See Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved (2005), Every Extend Extra (2006), Pac-Man Championship Edition (2007), and Galaga Legions (2008).

The emergence of these nostalgia projects was driven in part by the rise of digital distribution. At the time, broadband speeds weren't so speedy, and hard drives, especially on consoles, were snugger. The Xbox 360 "Elite" could only remember a maximum of 120 GB. So, the vanguard wave of downloadable games had to be compact, and companies were still figuring out how a slimline indie production should look. The natural points of reference were the pint-sized games of the past: the CRT hallucinations of the arcade epoch. Microsoft's downloadable games service was called Xbox LIVE Arcade. This arcade revival prefigured the resurgence of 80s culture in the early-mid 2010s and was prime real estate for Jeff Minter, who'd been developing software in this style for over 25 years. Minter made some of his most notable contributions during this period, co-creating the rail shooter Space Giraffe (2007) with Ivan Zorzin and providing art for Space Invaders Extreme (2009). Sorry, "SPACƎ INVADERS EXTRƎME".

From this point onwards, a bystander would probably assume that Minter's games were the etchings of someone who played the primaeval interactive software and wanted to imitate it. The reality is that he was one of the programmers making those games back in the day; he just kept going. Where other designers were tearing down video games' old scaffolding and rebuilding it, monk-like, Minter had spent decades refining the same form. And by 2017, he'd gotten pretty good at it, which brings us to our case study: Polybius.

Polybius was designed by Jeff Minter and programmed by Minter and Zorzin. Anyone can play it: your ship boosts forward continuously, and you use the left stick to move it along the X-axis and hold the A button to shoot. Levels often curve towards the left and right edges with your craft and camera always tilting to align with the ground under them. Hitting enemies reduces your lives and speed, while passing through gates and pulling off certain other stunts is an accelerator. Your score multiplier rises and falls with your velocity. Then there's the temporary deflector shield, which you can earn by, for example, sweeping through multiple gates in a row.

The system's single-page instruction book means that you don't have to hoof it through a tutorial before diving in at the deep end. Polybius opens by sliding you onto its checkerboard motorway and literally says, "Do what comes naturally", which happens to be strafe firing. Evolutionary psychology is quick to explain any instinct as being genetically ingrained. However, you can see gamers take to Polybius like ducks to water, and they can only have learned the demanded behaviour.

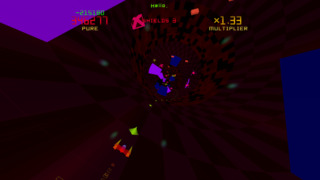

Polybius is one of the most intense experiences I've had with a computer, blending the whirlwind speed of Burnout with the fireworks of Geometry Wars. For Minter, the value of ferocious graphical processing power is not in ray tracing; it's in being able to speed up the tube shooter by having it run at 120 FPS. Expanding GPU memories are not for embiggening maps; they're for shoving a hundred exploding enemies onto screen at the same time. But Geometry Wars is one part aiming to one part dodging, and in Polybius, there's no independent aim vector. Shoot 'em ups have distinguished themselves from other gun-wielding games by locking your firing direction to the direction your avatar faces. Your avatar is often oriented towards the far end of the level, too.

Shmups may have fallen out of favour because they didn't have the freedom of aim and depth of control that other shooters did. However, by merging the aim vector and travel vector, games such as Galaga and DeathSmiles impose risk-reward dynamics. You must plant yourself in front of enemies to hit them, which puts you in their line of fire. Except in Polybius. In this world, you are moving too quickly, and the screen is too busy for it to task you with eradicating prey. Aiming a scope is right off the table. Because you don't have time to react to approaching heck and dart out of the way, Minter makes it so that your bullets pop enemy shots and can blaze a path through most obstacles. Due to this effective laser vision, as well as your need to enter gates, and the high cost of hitting traffic, your priority becomes flight rather than fight.

Polybius is a high-octane driving game and one that improves on some systems from one of my favourites: Burnout Paradise. You can't find yourself wrapped around a concrete barrier because you couldn't turn to enter a gap at 200 mph. Because, in Polybius, it never feels like you're pushing against an external force to change position; movement is very twitchy. Also because you travel in a straight line. Polybius can be one long highway as it eschews open-world geography, meaning the level design doesn't need endless turns and junctions to pipe you back to earlier areas. And crashing isn't an instant game-over either, nor does it zero out your velocity. It's actually a blessing in disguise as it slows your speed, making the stages temporarily easier.

Nonetheless, Polybius's biggest stumbling block is that it does not consistently give you the visual data to sidestep calamity. It would be reductionist to say that this is a consequence of your ship's acceleration and the volume of barriers. They don't help, but other culprits include the models in the foreground, a thick layer of camera effects, and too little colour contrast between textures. There is a string of dots you follow to find the next gate, and it drives me up the wall that that line is midnight blue, but the floor and background can often be dark colours or even another inky blue. Reaction times don't matter when you don't have the stimulus to react to.

The game does have a safety measure to offset the difficulty of reacting at speed: the deflector, but here, the UI does not come through for us. This shield is the thin line between confidence and caution, between ramming headlong into solids like a charging rhino and skirting around them like a frightened mouse. It then follows that the game should be transparent and prompt with us about when the deflector is going to run out. The greater the amount of danger an upcoming change in game state poses, the louder a game needs to flag that change. But in Polybius, our invincibility cage does not flash when it's about to break, and there's no warning sound. You can only take fleeting glances at the deflector timer at the top of the screen, which I'd advise against when you need your eyes on the road.

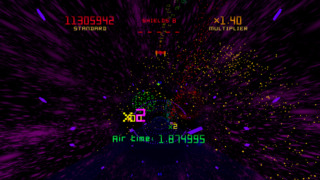

However, if you can get over that, Polybius is a game that is unreasonably good at inducing flow: the psychological state "in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter". The blurb at the beginning of the level Aorta calls this out, saying, "Seek the pure flow". As you can't look away from the game for even a second, it grabs your full attention. The air is thick with enemies, so rewards are constant, giving you an incentive to keep playing.

Polybius is as hypnotic as the fictional cabinet it takes its name from. In the tale, Polybius is a game invented by a vague yet menacing government agency, and it is intended to test mind control techniques. It's crack cocaine addictive, and many versions of the story have it subliminally messaging an unsuspecting public and causing seizures, among other malign effects. In a blog, Minter recounted playing Polybius in a warehouse in Basingstoke, hence the title of the 21st level and one of the most upsetting phrases in any game: "Holiday in Basingstoke". Like the rumoured machine, Minter's Polybius is an engine of compulsion whose strobing visuals could trigger seizures in photosensitive viewers. You'll also see odd words pop out of enemies and at level exits, spelling out messages like "Scorn lukewarm tea", Polybius's own subliminal ploy.

The shooter starred in another piece of media a couple of months after it debuted. When Nine Inch Nails published their synth metal track Less Than in July 2017, they did it with a music video that consisted of a woman playing Polybius on a CRT. The first verse of the song references "focus" and "hypnosis". In the video, the player maintains an unblinking stare with the game, and by the end, her eyes are a cloudy grey, as though it has taken over her mind.

A majority of art and entertainment juxtaposes the sensory with the narrative or didactic, and in those cases, it's pertinent to ask what that media is "about". When we do that, we unearth ideas that we can repeat even to someone who's not interfaced with that media. But in the face of abstract art, this question of subject matter breaks down as pure abstraction means no messaging and only experience. This is the nature of Polybius: it exists as a sensory overload which can only be experienced first-hand. I can tell you about my time with it, but I can't play it back to you.

Minter's work reminds me of the later Tetsuya Mizuguchi games: Rez, Lumines, Child of Eden, and Tetris Effect. They are uncut visual, aural, and tactile sensory stimuli, with special editions of Rez famously getting packaged with the Trance Vibrator to envelop the audience's whole body into the play. Like Rez, Polybius cribs from rave culture, mashing together laser-like wireframes, euphoric electronica, and a rush of neurotransmitters. One of Polybius's recurring collectables is oversized pills. So illicit! When I'm done with Polybius, I always feel like I've been somewhere other than my home for the last hour, like I'm walking out of a thumping club, ears ringing.

Before Polybius was a horror story, a prop in a NIN video, or a salute to raves, it was the name of an Ancient Greek historian. The use of the name "Polybius" in the urban legend may be a pun on the writer having been born in the Greek city of Arcadia. It also relates to Polybius's belief in the cruciality of eyewitness accounts in historical research.[1] The reference affirms Polybius, both the mythological and Minterlogical ones, as games centering direct psychoactive experience as opposed to interpretation, planning, or narrative. And there is one more meaning of that historian's name: the literal translation: "longlife".

The video game industry is a hotbed of brain drain, a professional revolving door. But imagine what could be produced if everyone got the chance to exist in this space as long as Minter has. If instead of alienating the people accumulating expertise, the business embraced them and let them apply that skillset to future projects for decades to come. Polybius is the result of someone establishing themselves in the field at a specific place and time, and leveraging the advancement of technology to grow the games of that period. Polybius is what happens when a format and a developer are given the time they need to bloom, and the result is hypnotising. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- Polybius by Frank W. Walbank (December 15, 2022), Britannica.

All other sources linked at relevant points in article.

Log in to comment