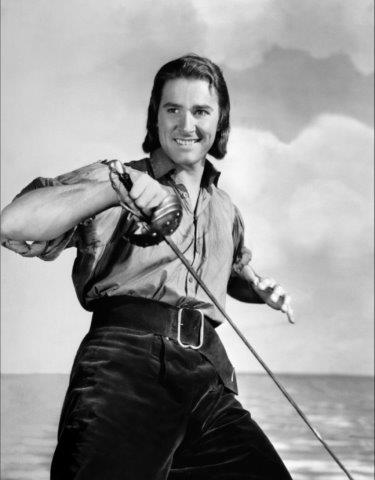

Captain Blood

Swashbuckler films had been popular in the 1920s (Douglas Fairbanks, etc), but fallen out of fashion with the Depression and the coming of sound. The success of The Count of Monte Cristo (1934) and Treasure Island (1934) prompted a revival in the genre, so Warner Bros looked at their back catalogue to see what pre-existing IP they might be able to reboot (plus ça change…): they decided on Rafael Sabatini’s novel Captain Blood. Previously filmed in 1924, it follows the career of physician Peter Blood, who is sentenced to death for treason during Monmouth’s Rebellion, sold into slavery in the West Indies, and escapes to become a notorious-but-actually-nice pirate.

But who to star? The big male actors at Warners tended to be suited more for gangster stories (Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Paul Muni) or musicals (Dick Powell). They tried to borrow Robert Donat, who had been in Monte Cristo, but he declined. Leslie Howard was considered.

They looked at their own contract players, including Flynn. He was tested. Then tested again. And again, and again. Because the tests were promising. Head of production Hal B. Wallis must have been excited – here was a potential action star under their very noses, one they could use for cheap rates, and people remember you more if you discover stars, etc, etc – but also nervous: Flynn was so green, this was going to be a $1.3 million movie, remember John Wayne in The Big Trail (1930) etc, etc. But who else could have played it? Ian Hunter? Brian Aherne? Both were tested. No one came close to the Tasmanian. He got the gig.

So again, Flynn was lucky – not just in being at the right place at the right time with the right lack of competition, but with his collaborators on Captain Blood.

For starters there was Sabatini’s superb source novel, whose quality was matched by Casey Robinson’s adaptation. So many later day pirate films floundered when it came to story (eg. Swashbuckler, Cutthroat Island, Pirates), it’s confusing why they didn’t just remake Captain Blood or at least rip it off because it’s marvelously written; within the first 20 minutes Errol has been caught up in Monmouth’s rebellion (the film is very pro-Protestant without saying so – but Spaniards and James II = bad, while the Duke of Monmouth and William of Orange = good), hauled in front of Judge Jeffries, shipped off to the West Indies, turned into a slave, become a doctor.

It was all brilliantly realised by director Michael Curtiz, his talented crew and magnificent cast. Basil Rathbone is sleek and sexy as a rival pirate, kind of the dark side of Flynn (Rathbone’s character is similar to what I imagine the real Flynn to have been like); Olivia de Havilland is a picture of innocence mixed with a dash of sauce; Guy Kibee and the assorted crew are great fun (including Ross Alexander who plays the significant Jeremy Pitt role – he looks a bit withered and tragic here and in real life he killed himself soon after the movie). Eric Wolfgang Korngold’s music score set new standards for this sort of thing, as did the battle sequences – actually you could say it for the whole movie. It’s a delight.

Curtiz re-shot Errol Flynn’s first two weeks of scenes and even then, the actor’s inexperience comes through at times, but he is perfect as Captain Blood: handsome, charismatic, idealistic, funny, charming. It would have helped that he was given so much action to do – Flynn was a natural athlete – and his romantic scenes were performed against the delectable Olivia de Havilland; the two had marvelous, natural chemistry – I especially love the bit at the end where she pretends to plead for her uncle’s life; it’s like two kids mucking around which is what filming probably felt like to them.

The gamble of casting him paid off in spades – the movie was a huge success and Flynn became one of that small group of actors who didn’t just become a star via one film, but a star around whom movies would be subsequently constructed; others in this club include Alan Ladd with This Gun for Hire (1944), Burt Lancaster in The Killers (1946) and Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl (1968).

The duel between Flynn and Rathbone below.

The Charge of the Light Brigade

Flynn had been set to follow Blood with Anthony Adverse (1936), playing the father of Frederic March, but public response to his pirate movie was so enthusiastic that Warners decided to instead put Flynn in his own vehicle – another period adventure tale, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) (his role in Adverse was taken by Louis Hayward who had an entirely decent career as a second tier Errol Flynn type, including two Captain Blood movies).

Charge was set partly in the Crimean War but mostly in British India, because Paramount’s Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) had been a hit (incidentally, Flynn later starred in a radio adaptation of Lancer – he was a decent radio actor, with an excellent speaking voice, and is much better in the radio version than Gary Cooper is in the movie). The guts of the plot involves a nasty rajah who wipes out a British garrison in India (based on the Cawnpore massacre of 1857), then flees to Crimea, chased by Errol and his fellow soldiers, who kill him in the Charge of the Light Brigade.

If you think that story sounds silly, you’d be right and it doesn’t come across any less so on screen: the climax involves Flynn forging an order so the charge can go ahead enabling him to kill the rajah, which, when you think about it, is really quite fanatical (oh, they throw in some reason that the charge is needed to save Sebastopol, but basically the whole thing is to take out one person). Mind you, the real-life Charge of the Light Brigade was caused by an officer making a mistake, so maybe it’s not too much of a historical distortion.

The other major flaw of the movie is the romance sub-plot, which consists of Olivia de Havilland being engaged to Flynn but secretly loving his brother, played by Patric Knowles (another discovery of Asher’s) – and she doesn’t change her mind. This is irritating because Knowles is such a wet actor, and his character is a loser (he never does anything brave, he thinks Errol won’t mind the fact de Havilland falls for him, then goes into a sulk when Errol gets pissed off).

I guess they did it this way because they knew Flynn was going to die in the final charge and wanted to have him do some noble gesture – but couldn’t they have made Knowles a bit more admirable? Or maybe have Errol only love Olivia secretly? When de Havilland kisses Knowles you feel that she’s cheating. It’s made even worse by the fact Flynn has no rapport with Knowles on screen – he’s got far more chemistry with David Niven (in real life, briefly a housemate of Flynn), who plays one of his solider mates.

On the positive side, Charge has three top-notch action sequences: an ambush where Errol saves the day, the siege and massacre (very effective), and the final charge (Tennyson’s poem is superimposed over the top, which is a bit distracting but you get used to it). Flynn has a great death scene, getting mortally wounded as he throws a lance into the rajah but lingering long enough to see the baddy get totally skewered. The production values are tremendous, as is the black and white photography – Michael Curtiz shoves the frame full of shots of shadows and marching troops. The film has too many flaws for me to class this as top-notch Flynn, but it was another box office hit, Warners’ most successful release of the year and the new star’s status was confirmed.

Green Light

Warners wondered if audiences would buy Flynn in other, cheaper genres, so they tried him in Green Light (1937), a medical melodrama where he plays a role meant for Leslie Howard: an idealistic doctor searching for a cure for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. It’s based on a novel by Lloyd C Douglas who also wrote Magnificent Obsession, and if you’ve seen the movies made from that book, you’ll have some idea of what this is like.

Flynn drives around in a sports car, smokes cigarettes and has women fall in love with him left, right and centre – his nurse with unrequited love, his patient who subsequently dies, the said patient’s daughter. Even the men seem to have crushes on him – the devoted research doctor who wants Errol to come with him to the mountains and find a cure for spotted fever, the dean who offers advice to all and sundry, the doctor whose negligence causes Errol’s disgrace. At the end of the movie, most of them are gathered round Errol’s bedside through ten minutes or so of “almost deathbed acting”, as Flynn fights spotted fever in order to test a serum.

There’s a lot of non-ironic talk about God and love, plus some comic stuff with a dog called Sylvia (to whom Errol asks, “what’s it all about?”). Actually, come to think of it, it’s more accurate to say there’s a comic moment – the rest of the film is deadly earnest, with violins constantly playing in the background.

Flynn’s performance is fine – there’s not really much for him to do, his character doesn’t really go on any sort of journey: he’s a nice guy to start off with, he only gets in trouble because he does something noble; he hits the bottle one time and doesn’t believe in religion, but that’s about it, and those things are quickly sorted.

Still, the film made money, and Flynn would go on to appear in several more melodramas in his career. (He’d also perform them on radio – he was in an adaptation of These Three, which is worth listening to.)

Flynn did a radio version of the movie, you can listen to it below.

The Prince and the Pauper

His next movie was more typical – an adaptation of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper (1937). This was really a vehicle for Billy and Bobby Mauch, twins who had starred in some shorts and were under contract to Warners (this is their only real film of note), but there was a decent support part for a soldier of fortune who befriends the prince. It was originally going to be played by Patrick Knowles (Ian Hunter and George Brent were also in the running) but as the film’s budget grew, Warners became nervous and gave the role to Flynn at the last minute for extra box office insurance. Artistically, it probably wouldn’t have made that much difference. Commercially, it was a wise decision – it was the studio’s most popular film of the year, with Green Light coming in second.

By 1937, audiences had seen the swashbuckling Errol, noble Errol, rebel Errol, romantic Errol and noble Errol – The Prince and the Pauper gave them Cool Big Brother Errol. The movie is a kids’ fantasy: you either find out you’re identical to the king and get to rule a country (everyone does what you want), or if you become a pauper, a sword fighter will come along and look after you like a big brother.

The plot is kind of simple, but Warners gave the film the A treatment: Eric Wolfgang Korngold did the score, Claude Rains is the villain, the cast also includes Henry Stephenson, Alan Hale (as a guard Rains sends to kill Edward VI – he has a so-so duel with Errol, it’s their first movie together) and Montague Love (playing an unsympathetic Henry VIII – the film sticks to how he treated Catholics – was this due to the influence of the Legion of Decency?). The film drags in places, like the ending running-around-at-the-coronation sequence, and feels as though it could have done with a bit more fun, but it is a solid swashbuckler, ideal for kids especially, and served as a useful trial run for many of the cast and crew for Adventures of Robin Hood.

Here’s a clip of a sword fight in the film.

Another Dawn

There was more melodrama with Another Dawn (1937), starring Kay Francis as a woman who marries a British officer (Ian Hunter), goes to live with him at a fictitious colonial outpost somewhere in the Middle East, where she falls for her husband’s best friend (Flynn), who reminds her of the dead pilot she “loved” for “three ecstatic years” (outside of wedlock, I presume, which is a bit naughty).

This is a Kay Francis movie rather than an Errol one, and she’s quite good – pretty, with a distinct throaty voice, even if she spends most of the movie delivering dialogue while looking off into the distance. She plays an interesting character – an American independent woman of means, sexually active, a bit of a necrophiliac: she mainly falls for Errol because she reminds him of her ex, not because of anything special about him. They make eyes at each other but fight the attraction out of devotion to Hunter – fortunately some pesky rebellious Arabs come along, enabling Hunter to sacrifice his life while killing them, so the others can be happy.

There’s a fascinating scene where Errol’s sister (played by Frieda Inescort) admits she’s carried a torch for Ian Hunter for seven years – seven! – and tells Errol about the benefits of such a one-sided relationship: you can look on wistfully enjoying their achievements, etc. Talk about promoting self-flagellating relationships! Actually, there’s a lot of philosophical chat in this movie, some of it is surprisingly interesting; the late Bill Collins (who introduced me to so many Errol Flynn movies) always wrote well of Another Dawn.

Errol is romantic and dashing, though there’s only one action sequence (an Arab ambush – we never see the climactic bombing raid). Ian Hunter acquits himself quite well, with the professional aplomb of an actor who’s resigned to accepting that Errol will out-charisma him (he doesn’t even get a death scene).

The movie was not a massive hit at the box office, but was profitable. Flynn whinged a lot during filming – he disliked his role and director William Dieterle. This may explain why Warners then decided to put him in a comedy.

A clip from Another Dawn below.

The Perfect Specimen

Most movie stars of the thirties tried a screwball comedy at some stage and Flynn got his chance with The Perfect Specimen (1937), playing a man who has grown up isolated from society and is taken out on a lark by a wisecracking dame (Joan Blondell, in a role Miriam Hopkins turned down). It’s based on a story by the guy who wrote the story for It Happened One Night (1935) and feels like that movie; the basic idea has some similarities with the Ivan Reitman comedy Twins (1988).

Errol is very handsome and charming in the title role; his inexperience in comedy actually suits the part as he plays a person not used to the outside world. Not that he has much of a character to depict – there’s tremendous potential in the concept, about a perfect person who has been protected and then proceeds to have fish out of water adventures – but it isn’t really used.

The story isn’t strong – Errol and Blondell head out for a day, he winds up doing a bit of boxing (Flynn excelled at this sport in real life), then he hooks up with a poet who I think is meant to be colourful, and Flynn and Blondell have a quite romantic and sexy scene drying themselves off after the rain… All while the nation thinks Errol has been kidnapped – which actually isn’t very funny, because cops are wasting time chasing after someone who isn’t in danger.

There needed to be a stronger reason why Blondell takes Errol out for the day – why didn’t they just make her a reporter like Gable in It Happened One Night (that means she would deceive Errol, creating extra drama)? And the finale is far too easily resolved, with Blondell’s brother easily tracking them down and conveniently wanting to marry Errol’s fiancée.

The film badly needs an antagonist, someone who is on Errol’s trail, and some decent adventures on the road – there are not really any decent jokes, just high spirits; Curtiz was a great director when it came to pace and action, but he didn’t have Frank Capra’s skill at filming warm encounters with eccentrics.

Still, it’s easy to watch. Flynn has a fine old time and Blondell is charming as his feisty love interest; she was often stuck playing comic relief best friends, but here, she’s given a bit of glamour treatment and nice photography. It skips along at a bright pace, has charm, and would turn out to be the most financially successful of all Flynn’s comedies.

Errol Flynn the Writer

Flynn had long been interested in writing, and during his New Guinea days, occasionally submitted articles for the Australian magazine The Bulletin. He continued to write even after becoming a movie star; despite all the distractions that must have come with instant wealth and fame (which included a yacht he was fond of taking out on long voyages), he was disciplined enough to pen a novel which was published in 1937 – a fictionalised account of his experiences sailing around Australia, Beam Ends.

He also tried his hand at a film script, a biopic of Sir James Brooke called The White Rajah, which Warners announced for production several times in the late 1930s but kept being postponed and was eventually cancelled, mostly due to opposition from Brooke’s family (a shame because Flynn would have made the perfect Brooke).

In 1937 he travelled with Erben to Spain to be a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War (it was remarkable that a movie star would head off to a war zone for the sheer fun of it, and indeed he was almost killed by shrapnel, but that was Flynn for you).

Writing clearly bought great joy and satisfaction to him – although like all writers he would have experienced frustration and dissatisfaction as well. As years went on, Flynn’s alcoholism hampered his ability to write effectively, but he never lost his love for it.

The Adventures of Robin Hood

Warners were now so secure in Flynn’s appeal they assigned the biggest budget in the studio’s history to The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), starring Flynn as the title role (though James Cagney had at one stage been considered and you know something, he would’ve been a lot of fun. Ex dancers usually make good swashbucklers – look at Gene Kelly in The Three Musketeers (1948).)

The resulting movie is a delight, still the best version of this story ever put on screen. There never was a more perfect fairytale Robin Hood than Errol Flynn, all sparkling teeth and green tights, bursting into the castle with a stag over his shoulders, throwing it on the table. He’s more than matched by Olivia de Havilland, exquisite as Maid Marian, a little imperious but basically nice, very brave in a trembling school virgin way, but with a twinkle in her eye to match Flynn’s – when she drags him off at the end, you know it’s going to be a lively honeymoon for Robin.

The support cast is dazzling: the silky villainy of Claude Rains as King John (he has some lovely justifications for the things he does and his look at the end – “but I’m your brother” – is priceless), the smooth Basil Rathbone as Sir Guy of Gisborne, bluff hearty Alan Hale as Little John, spunky Eugene Palatte as Friar Tuck.

The film keeps hitting bullseyes all the way through: the scene where King John and company are wondering about how to find Robin and he just saunters in; the fight on the log between Little John and Robin; Robin meeting with Friar Tuck; the balcony scene between Robin and Marian; the archery competition; the reveal of King Richard’s identity (what a thrill to see Ian Hunter pull back his cloak to show who he is); the final battle (for some reason the sword fight between Flynn and Rathbone here isn’t as highly regarded amongst connoisseurs as Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk, maybe because it doesn’t involve rapiers, but I love it just as much); the sumptuous music.

Occasionally, there are what surely must be unintended laughs: the Merry Men are a bit too Merry at times, Will Scarlett (Patric Knowles) looks like a complete wimp playing his lute and laughing on the river bank while Robin fights Little John. I also think it was a mistake for the Merry Men to capture Basil Rathbone, then let him go – it devalues him as an antagonist. Melville C Cooper’s Sheriff of Nottingham is more buffoonish than a threat – though the filmmakers probably figured with Rathbone and Rains they could afford a more comic villain, and Nottingham does come up with the clever archery tournament trap – and there is an extra villain most people forget, the cardinal played by Montagu Love. (People sometimes forget, too – I know I do – Herbert Mundin as Much the Miller’s Son, who gets quite a long sequence towards the end when he has to kill a henchman of Rathbone’s).

Considering all the hands that went into this – two directors, several writers (Seton I Miller is one of the forgotten heroes of Errol Flynn’s career), lots of studio notes – it runs very smoothly and is a tribute to the power of the Hollywood factory at its peak. And only 98 minutes, too. The film was a huge box office hit and has never stopped playing.

The sword fight is below.

Four’s a Crowd

Flynn followed it with another screwball comedy, Four’s a Crowd (1938), co-starring de Havilland, Rosalind Russell and Knowles. The basic idea for this film isn’t much – it’s really just about PR man Flynn trying to nab rich Walter Connolly as a client (low stakes) – but given that it’s as if the filmmakers then went, “right, let’s make the best movie we can”, and they went for it. So, you have a silly, weak central idea done with tremendous vim and gusto.

The script is mostly a collection of set pieces – there’s a sequence in a nightclub behind a coffin, one where Flynn breaks into Connolly’s house to sabotage a model train race (it’s that sort of script), the model train race, Errol having two dates for the night, the final wedding sequence. Michael Curtiz directs at a break neck speed, and there’s even some believable sentimentality where Flynn engineers Connolly to donate money to an infantile paralysis centre.

Flynn has the time of his life as the unscrupulous PR man, and watching him in this, I think he could have even handled being in something like His Girl Friday – especially as he bounces so well off Rosalind Russell, who plays a reporter.

Russell is usually excellent playing snappy reporters and she is so here; so too is Olivia de Havilland as a slightly dim but energetic heiress, always up for a bit of fun. Indeed, this is surprisingly sexy, with couple swapping, Flynn wooing both Olivia and Ros and both enjoying it, and a scene of the three of them running around the pool in their bathers. Patric Knowles is a bit of a drag as the fourth lead – he tries his best, but it’s like watching three gold-plated stars and poor old platinum Patric. But don’t worry, they shunt him out of the way for most the running time. (If you think I’m being mean about Patrick Knowles, well, I wasn’t alone… Warners soon turfed him, and he went over to RKO and Universal, where he never stopped being bland.)

Unfortunately, the public did not particularly like the movie – it was Flynn’s least successful release since he became a star. Warners recoiled from putting him in any more comedies for now.

The Sisters

Flynn went into his second melodrama-based-on-a-best-seller, The Sisters (1938), which focuses on the lives and loves of three sisters over several years at the beginning of the 20th century. Well, that’s how it was in the original novel, but in the film, two of the sisters (Jane Bryan, Anita Louise) don’t get much of a look in; the bulk of the running time is taken up by sister Bette Davis and Flynn, who plays the ne-er-do-well journalist she loves and loses.

Flynn’s quite effective in his least sympathetic part to date, a weak, insecure man with aspirations to write a novel but can never go through with it, and it suits him… possibly accessing the weakness and insecurity that was within the real Flynn. The depiction of his abusive treatment of Davis is all too convincing – the drinking, emotional and physical abuse, manipulation, interspersed with the periods of remorse and well-meaning, but ultimately futile promises to change… It makes the movie feel very current.

In the original ending, Davis wound up with her boss, played by Ian Hunter, but test audiences complained (poor Hunter was always losing out to Errol), so Warners introduced an alternative where she is reunited with Flynn. The two actors hated these new scenes and Flynn even told the press he would refuse to film them – but money is money, and the “happy” ending was added, where Davis goes back to her abusive husband, who clearly still has a drinking problem. I wonder if the film prompted any women in the audience to give their deadbeat hubbies another chance and wound up in horrible circumstances as a result.

In the movie’s defence, as a piece of melodrama it is effective, with a strong cast and excellent production design, including a very subtle depiction of a brothel and a fine re-creation of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Here is that earthquake scene.

The Dawn Patrol

Flynn toplined The Dawn Patrol (1938), a remake of a 1930 drama about Royal Flying Corps fighter pilots in World War One. It’s an intense drama of the “Journey’s End” school, very anti-war, full of stiff upper lips and wondering about the slaughter – yes, it became a cliche, but it wasn’t here, and it is still powerful, mostly because it really happened and the film was made by war veterans – including director Edmund Goulding, stars Basil Rathbone and David Niven (who hadn’t seen action yet but whose father had died at Gallipoli), and co-writer John Monk Saunders. And for all the jolly-good-chaps dialogue and befriending Germans who’ve tried to kill them, there’s no denying the characters’ desperation as they booze away and try not to think about tomorrow because that’s when they might be killed.

Flynn gives an excellent performance, the perfect dashing hero tired by war but trying to keep his spirits up – he’s maybe in a little over his head in the later scenes when his character takes command, but since his character is over his head, it suits. Niven is excellent, too – he and Flynn have real camaraderie, their boozing jousting sessions feel natural and warm – and I love the use of zoom on Flynn by Goulding when Flynn realises Niven’s not dead like he thought.

There are three main action sequences – two involving Flynn in which, despite all the film’s ostensible anti-war stance, he is shown to demolish the Germans pretty easily. (Like Charge of the Light Brigade and Another Dawn, he and a friend squabble over who gets to go on a suicide mission at the end – suicide missions were very big in 1930s cinema).

Goulding’s handling is superb. Fans of the “male gaze” from gay directors may get something from analysing this all-male war film: note the number of pretty young boys in minor roles, such as the one who has a breakdown because his “best friend” dies (he can’t understand why Flynn doesn’t get as upset when he thinks Niven is dead). It’s not overt, just different from the handling of, say, a Raoul Walsh or Michael Curtiz.

The movie was a big success at the box office – Warners’ third most popular release in 1939. The second was the gangster classic Angels with Dirty Faces. The first was Flynn’s next movie…

Dodge City

Most Westerns in the 1930s were low budget jobs, but the genre made a respectability comeback towards the end of the decade and Warners wanted to try one with Flynn, their number one action guy. He was reluctant, unsure his image and accent would suit the genre, but it certainly fitted better than the other leading men Warners had available, like Edward G Robinson and George Raft (mind you, the studio also trialed the very urban James Cagney in a Western that year – The Oklahoma City (1939)).

Hal Wallis laid on all the trimmings for Dodge City (1939): a massive budget, colour, Michael Curtiz as director, de Havilland as co-star, and expensive production values (scores of extras, trains, cattle, brawls). The film is packed with strong action sequences (a race between a stagecoach and train, a cattle stampede, a final battle on the fire-riddled train, the famous brawl sequence – which is best as a spectacle rather than something genuinely exciting, but still highly enjoyable).

The ramshackle plot sort of ambles around from set piece to set piece (did we need that scene on the establishment of Dodge City?; Errol doesn’t put on the badge til around an hour into it; what sort of character is this Col Dodge if he lets towns named after him go to rack and ruin?), but basically works.

Flynn is in good form, especially with de Havilland; I buy him in a Western (as did audiences, and he would make a stack of them over the next decade, more than swashbucklers in fact), but can’t help wishing his Irish adventurer character was a little more roguish – for instance, when he visits Ann Sheridan at the saloon (in the role that really got her attention in Hollywood), you really want some sparks to fly between them.

The support cast is very good: Bruce Cabot and Victor Jory make an imposing pair of villains, Alan Hale has a hilarious scene when he visits a temperance meeting, Ann Sheridan has only a few lines of dialogue but gets to sing three songs and looks sensational in technicolor. The film isn’t afraid to go for it – the annoying “cute” kid is killed off (would such a thing happen today? Probably not, they’d just injure him.) Re-watching this recently, I was surprised how many scenes remained vivid in my memory from childhood: the death of the newspaper editor; the fight on the train; the wagon train sequence with people riding on horses from one to another like public transport; the brawl.

The film was a huge hit, Warners’ most popular movie of 1939. Flynn would go on to make a number of Westerns and he would be the only non-American star to be consistently successful in that genre.

Here is the brawl.

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex

Flynn was reunited with Davis, Curtiz and de Havilland in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), playing the Earl of Essex who has a (mostly fictitious) romance with Queen Elizabeth I (Davis). Davis was unhappy with his casting – she wanted Laurence Olivier, who would have probably given an excellent performance, but one can’t blame Warners for casting Flynn, especially as the character of Essex was ideal for the actor: spoilt, handsome, impetuous, unstable. Indeed, it’s frustrating Errol didn’t take the role more seriously and try harder, because this really could have established him in dramatic parts.

But he’s disappointing. I don’t want him to be, but he is. The script is partly to blame – it would have been better if Essex had been more of an opportunist; certainly elements of that are present in the character here, but they try to have it both ways by claiming Essex genuinely loved Elizabeth, and saying there were other villains at work (the “villains” being Raleigh, Cecil and Burghley who suppress Essex and Elizabeth’s correspondence while the former is in Ireland, thus being the ones responsible for Essex’s failure to defeat Tyrone, not Essex). It’s a shame the film didn’t have the guts to be a good old fashioned woman-in-love-with-a-loser story – the emotional kick would have been stronger; it sort of half is, but doesn’t go the whole way; still puts a bit of shine on Essex.

Flynn is wooden in several scenes, especially when he has to be serious (you never believe he really loves Davis – which is why I think it would have been a better movie had he been playing “pretend”, the woodenness would have been appropriate). Apparently, Flynn freaked out a little during the making of the movie with all the dialogue, Bette Davis hassle and unsympathetic direction from Michael Curtiz (he and Flynn were really getting on each other’s nerves by now); it’s a shame that Edmund Goulding didn’t direct this. Flynn has his moments, though, especially arguing and flirting with Davis; he’s also strong with his on-screen antagonists, Alan Hale, Vincent Price and company.

Davis is in fine showy form and there is plenty of meaty drama – history is telescoped as it must, but the story is not without some historical interest. The strongest scenes are when Essex and Elizabeth have their flirty scene punctuated by quarrels, when Essex comes back to Ireland, and the (entirely fictional but dramatically excellent) meeting of the two lovers just before his head gets chopped off.

De Havilland is completely wasted in her role – Jack Warner forced her to play the part out of punishment for her doing so well in Gone with the Wind. There is gorgeous Sol Polito colour photography and plenty of production values and Michael Curtiz shadows. The movie was a solid success, though slightly disappointing considering its large budget.

A clip is below.

Errol Flynn had arrived in England in 1933 as a penniless, debt-addled adventurer. By 1939, Quigley Publications listed him as the eighth biggest box office draw in the country. He was under contract to a large studio, which was dedicated to creating vehicles for him to star in.

But life was about to get more complicated. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, triggering World War Two. The “war phase” of Errol Flynn’s career was about to begin. And with it, his luck started to turn…

Appendix Box Office figures of Flynn’s films 1935-39

Captain Blood – cost $995,000, earnings $2,475,000

The Charge of the Light Brigade – cost $1,076,000, earnings $2,736,000

Green Light – cost $513,000 earnings $1,667,000

The Prince and the Pauper – cost $858,000 earnings $1,691,000

Another Dawn – cost $552,000 earnings $1,045,000

The Adventures of Robin Hood – cost $2,033,000 earnings $3,981,000

The Perfect Specimen – cost $505,000 earnings $1,281,000

The Dawn Patrol – cost $500,000 earnings $2,185,000

Dodge City – cost $1,061,000 earnings $2,532,000

The Private Life of Elizabeth and Essex – cost $1,073,000 earnings $1,613,000

Figures for “Four’s a Crowd” and “The Sisters” are not available

Source: Warner Bros Financial Data, The William Shaefer Ledger.

Comments

Wow, he gets away with slapping a woman’s bum, and not just any bum, the “Virgin Queen’s bum.

I wouldn’t be trying that move in 2021 mate!