Mexico has declared 2023 as the Year of Francisco “Pancho” Villa.

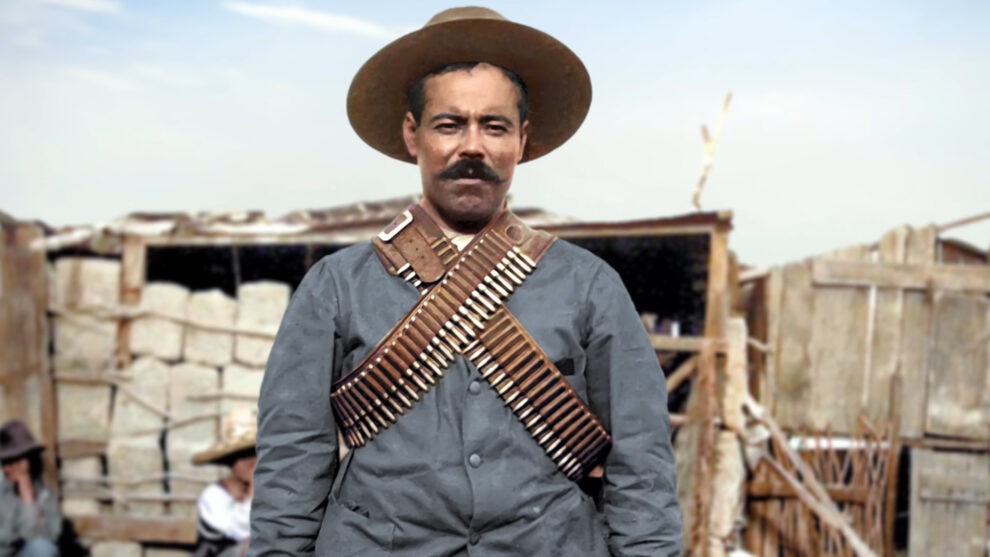

Does that name ring a giant bell? Most probably yes. Villa was the popular revolutionary with the mustache, big hat and guns who in the 1910s fought against the dictatorship and to raise the living standards of the poor.

He was born around 1878 in a village of no more than six houses, but achieved worldwide fame after dedicating himself to various trades, including rustling and freedom fighter. He rose to fame when in 1914 he advanced with his peasant army from Chihuahua to the National Palace in the Mexican capital.

Already in his lifetime Villa was the stuff of legends. He was feared, hated and had an incredible appeal; songs were composed about him and he inhabited the popular imagination as a kind of Robin Hood.

Today he is one of the revered figures of Mexican history, there are streets and squares named after him, but his official “canonization” was slow, first of all because his integrity has not always been clear to those who knew him and those who have subsequently studied his life and legacy.

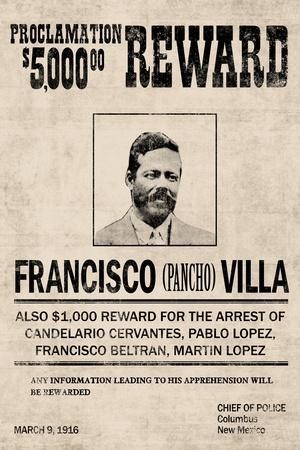

Was Pancho Villa a fine hero or a bandit with charisma and a huge army, not to mention great PR men?

2023 is the year of Francisco Villa because it marks the 100th anniversary of his macabre death: the then-ex-revolutionary was pierced by bullets and left hanging upside down from the window of his car. It looked like a scene from a gangster movie.

Villa, by the way, was not called Pancho or Francisco, but Doroteo, a name that means gift or “deed of God.” Which god is up for discussion, depending on whom we ask.

Villa was the people’s revolutionary, but he was also a cruel, arbitrary, bloodthirsty man, and at his worst moments he was a xenophobe (against the Chinese in northern Mexico) and a terrorist (in Columbus, NM) almost dragging his country into a new international war. He was generous and smiling with one hand, brutal and ruthless with the other.

However, in his moments of greatness he had a social ideal, kind dispositions for his people, and a collectivist and paternalistic vision of a government where peace coexisted with justice. He lived this utopian vision at the end of his life in the hacienda where he retired with his last men.

- Opinion: Biden Must Renew DACA

- A 400 Year Visual History Of Chicano Literature

- Chicano Heroes: The Art of Jorge Garza

Villa was a man of many contradictions.

”He is without any doubt the greatest leader Mexico has ever had,” wrote John Reed, an obviously devout American journalist who rode with him. But there are so many testimonies of his brutality, his savagery and the meaningless destruction he caused, that he will possibly never be considered a bona fide hero.

Many Mexicans boast that Villa taught the gringos a lesson, and to this day many claim that his is the only army ever to have invaded the United States (an exaggerated claim), and that he won a war against the US by defeating General Pershing (a decidedly false claim).

Yet for much of his life, Villa courted Hollywood and American journalists, had ambassadors and lobbyists in Washington, and a special envoy of President Woodrow Wilson among his ranks. Not to mention he enjoyed visiting Texas to immerse himself in American culture and indulge himself in its delicacies: strawberry milkshake, peanut candy and pancakes.

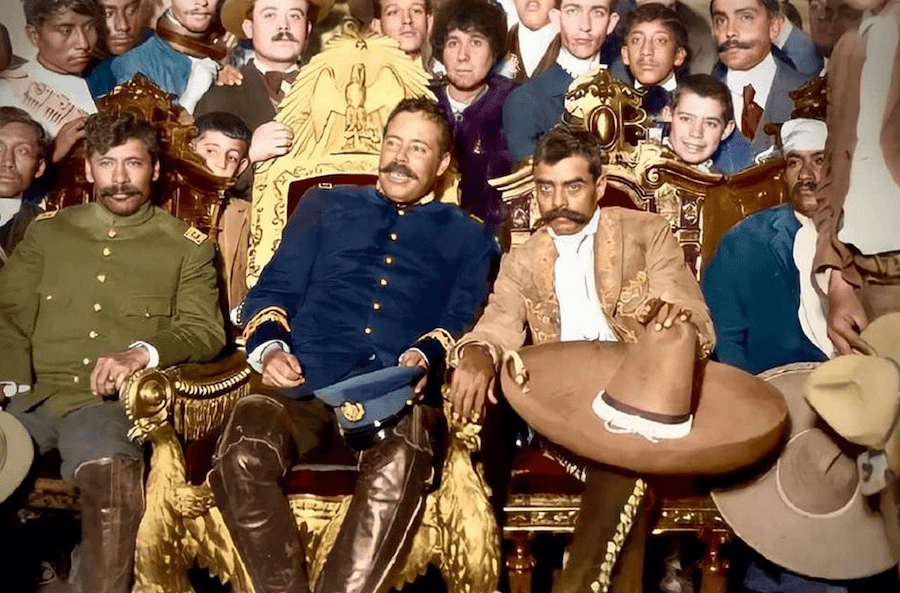

His military deeds were decisive in overthrowing the dictatorship and, presumably, bringing the popular classes to power. But beyond vague ideas, Villa had neither a social agenda nor a political program. And when he sat in the presidential chair for fifteen minutes, he openly admitted that politics were not for him, sat up and returned to the place from where he came.

He is seen as the epitome of manliness and bravery, yet he knelt down and begged in front of the firing squad (they spared his life) while others considered as soft (Emperor Maximilian) died as real valiants. He was decidedly macho, but he was also a teetotaler. Uneducated but intelligent, and decidedly a virile warrior who had no qualms about crying rivers in public.

It is not then surprising then that for a long time, official historians avoided making a verdict about Villa. It was only in 1976, more than half a century after his death, that his remains were transferred to the Monumento a la Revolución by a populist president, one well-remembered for his animosity towards the United States. In 1989 the city of Zacatecas unveiled a giant sculpture of an imposing, towering Villa riding his horse at the top of Bufa Hill (el Cerro de la Bufa).

Assessing and remembering Villa in his year of 2023 will be a decidedly complex and risky task. We don’t have him present anymore, but it would be interesting if the man himself could weigh in and possibly laugh at our attempts to understand him.

“They used to call me a bandit, and I suppose some still call me that,” he would say to us, as he told reporter Edmond Behr in 1913: “My heart is clean. My sole ambition was to rid Mexico of the class that has oppressed her and give the people a chance to know what real liberty means. If I could bring that about by giving up my life, I would do it gladly.”