Weekend Long Read: What a Minnesota Mural of Confucius Says About Misinterpretation

There is a mural of Confucius in a courtroom of the Minnesota Supreme Court in the U.S. It represents a misinterpretation in the search for likeness between China and the Western world.

The Minnesota Supreme Court has two courtrooms. The older one is on the second floor of the Minnesota State Capitol. From 1905 to 1990, the Minnesota Supreme Court heard its cases in the old courtroom. Some cases are still handled there despite the new judicial center of Minnesota being opened in 1990.

|

| Minnesota spent $300 million to renovate its state capitol building from 2012 to 2017. |

The old courtroom is stately and elegant, with elaborate decorations. The golden inscription “Lex” on an overhanging eave inside the courtroom means “law” in Latin. The dome of the courtroom is adorned with four semicircular murals, each depicting a historical scene that allegorically conveys a legal concept or principle, and portraying the development and progress of legal and social relations.

The mural right above the seats of the grand justices shows Moses receiving God’s Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai — a scene that suggests moral consciousness and sacred law divide civilization from barbarism. The one above the entrance shows the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates discussing philosophical matters. Socrates is known for inspiring his students with the unique “Socratic Method,” which is a major teaching tool in mainstream legal education and a common technique used by appellate judges to question lawyers. The mural on the right side of the dome tells a story about the Middle Ages when Raymond of Toulouse met with church representatives, trying to resolve disputes peacefully. This mechanism for resolving conflicting interests and seeking equity evolved into the court system.

|

The interior of the renovated Minnesota State Capitol. |

On the left side of the dome is a mural called “The Recording of Precedents,” which depicts Confucius and his disciples compiling documents and recording classics and laws.

The four murals were painted by John La Farge, a painter and decorator of the late 19th century. Born in New York in 1835, La Farge had an early interest in the law, but decided to pursue art after a trip to Paris in 1856. He was one of the first in America to adopt the formalism and paradigms of Japanese art in their works.

La Farge was 71 years old when he painted the four murals in Minnesota in 1906. These, together with his justice-themed murals for the Court of Appeals of Maryland in Baltimore, are considered his best works, and classic American murals of the 19th century.

In the China-set mural, Confucius and his disciples sit cross-legged in a forest, reading documents and recording history. This is not a specific historical moment, but an idealistic scene showing how ancient oriental philosophers valued history and law, leaving records for posterity. On the rightmost side, a disciple of Confucius holds a scroll that reads, “The business of laying on the colors follows the preparation of the plain ground (绘事后素).”

According to a biography, it was La Farge who instructed his Japanese assistant Okakura to add this Confucius maxim from Part III (Ba Yi,《论语•八佾》) of “The Analects of Confucius.” Today, we use it as a metaphor for an essential incremental process from simplicity to elaboration.

|

John La Farge’s mural “The Recording of Precedents” inside the capitol building. |

In the early days of the painting of these murals, La Farge came into conflict with the board of directors in charge of logistics in the Minnesota State Capitol, who complained about its progress, even delaying his payment because of it. However, La Farge thought the board did not understand the painting process, which required sketching before coloring. In the end, he completed the task on time, but left this Chinese allusion to imply the executives’ ignorance of art. It is also noted that the maxim has another important implication related to social governance.

In the context of the book, Tsze-hsia asks, “What is the meaning of ‘The pretty dimples of her artful smile! The well-defined black and white of her eyes! The plain ground for the colors!’?” Confucius says, “The business of laying on the colors follows the preparation of the plain ground.” “Ceremonies then are a subsequent thing?” Confucius answers, “It is Shang who can bring out what I truly mean. Now I can begin to talk about the odes with him.” They seem to be talking about painting techniques, but in fact, they are discussing social order and governance, specifically the priority order of “humaneness” and “propriety.” It was concluded that humaneness, as the cornerstone of cultivation, comes before propriety (仁先礼后). As Confucius puts it, “It is only when the natural qualities and the results of education are properly blended, that we have the truly wise and good man (文质彬彬,然后君子).”

La Farge visited Japan in 1886 and published “An Artist’s Letters from Japan” in 1887, presenting his in-depth thoughts about Japanese literature, which was under the enormous influence of Confucian aesthetics. We have no way of verifying whether he agreed with Confucius’s idea about propriety. But his incorporation of Confucius into “The Recording of Precedents” may suggest that he believed that Confucius respected history and legal precedents, and that such respect was somehow consistent with the trajectory of legal civilization. Besides, the maxim in the mural can be applied to the legal field: legal precedents are the basis of a well-supported trial.

However, an association between Confucius and legal precedents is ill-founded.

Confucius had an ambiguous attitude toward historical records, which can be supported by his expurgation of the “Book of Songs (诗),” “Book of Documents (书)” and “Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋).” For major records of historical and contemporary events that were uncertain, he remained cautious. He neither detailed such stories, nor denied them flatly, but he did try to convey profound meaning with subtle words. In addition, Confucius avoided “mentioning certain facts about his superiors, his close kin and virtuous men (为尊者讳,为亲者讳,为贤者讳)” to show his respect when recording history, as he did in the “Spring and Autumn Annals.”

Speaking of law, Confucius opposed formulating and promulgating criminal laws. As explained by the American sinologist Benjamin Schwartz in his book “The World of Thought in Ancient China,” Confucius might agree that the code dictates people’s conduct with a behavior pattern, while the nobility directs people’s conduct by setting a moral example; the promulgation of laws will intensify their dominance over people, and will inevitably weaken the nobility’s moral guidance. Such a society, however, does not seem to conform to “propriety.”

In this sense, it may be a misinterpretation of cultural resemblance to view Confucius as someone who particularly respected the law or documented precedents.

Although La Farge cared much about cultural differences, he realized he had had made the error of painting Confucius’ clothes gold only after he had finished the entire mural, when a book he read mentioned that Confucius found it inappropriate to wear gold-colored attire. Therefore, he recolored the sage’s clothes and adjusted the color of the whole mural. Despite this carefulness, the anachronistic scrolls (which would have been bamboo slips in Confucius’ time) and the disciples’ Qing Dynasty Manchu hairstyles didn’t save the painter from embarrassment, although a layman would not notice them.

|

A close-up of La Farge’s depiction of Confucius. |

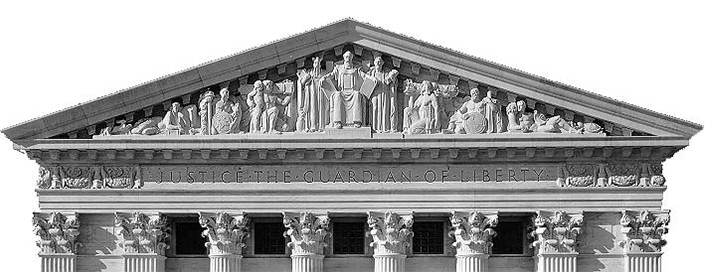

In America, Confucius is a symbol of oriental wisdom and a personification of ancient Chinese law. His figure can be found not only in the Minnesota Supreme Court, but also in the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington. Under the eastern eaves of the Supreme Court, there is a suite of reliefs called “Justice the Guardian of Liberty,” representing ancient oriental civilization as a source of modern legal thought. Moses, Thoreau and Confucius are placed in the middle and revered as three great lawgivers.

|

The eastern eaves of the U.S. Supreme Court. |

Yue Daiyun, a leading figure in Chinese comparative literature, once said, “Misinterpretation happens when people try to apply whatever they are familiar with, be it their own cultural tradition or mode of thinking, to interpreting another culture.” Such misinterpretation is universal: the West may misread the East, and vice versa. Anyone may misunderstand others.

In the dialogue between eastern and western legal traditions and cultures, we inevitably judge each other as our mode of thinking is subject to the restriction of our cultural and linguistic environments. The Italian historian Benedetto Croce emphasized, “All history is contemporary history.” That is because historians cannot detach themselves from the time they are in and their cognitive system.

We all interpret the past for the sake of the present. Perhaps we can put it this way: the West is portraying itself when characterising the East, and the East is portraying itself when characterising the West.

Wang Chang is an associate professor at the College of Comparative Law, China University of Political Science and Law; and an adjunct professor at the University of Minnesota in the U.S.

Contact editor Heather Mowbray (heathermowbray@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- MOST POPULAR