Illustrating Confucian influences in contemporary East Asian religious practices can be challenging. Studies usually address Confucian religious practices in two ways. First, Confucian principles and values are identified as intrinsic, and yet implicit, in modern East Asian culture. T. R. Reid’s Confucius Lives Next Door is a good example of this approach,usually these studies will compare East Asian societies to the West, with distinctions in attributes such as societal order, family reverence, and educational discipline attributed to Confucian values.1 Second, Confucian practice may be identified within the practices of the “three teachings” (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism). In Japan, Confucian principles often inform and shape Buddhist and Shinto teachings and rituals. Confucian values of ancestor veneration influence both funeral rites and annual observances in remembrance of one’s kindred dead. Confucian virtues regarding learning and education are illustrated by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines offering various charms, amulets, votive tablets, and good-luck pieces for educational success. Ian Reader and George J. Tanabe, Jr.’s Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan is a good example of this approach.2

Illustrating Confucian influences in contemporary East Asian religious practices can be challenging. Studies usually address Confucian religious practices in two ways. First, Confucian principles and values are identified as intrinsic, and yet implicit, in modern East Asian culture. T. R. Reid’s Confucius Lives Next Door is a good example of this approach,usually these studies will compare East Asian societies to the West, with distinctions in attributes such as societal order, family reverence, and educational discipline attributed to Confucian values.1 Second, Confucian practice may be identified within the practices of the “three teachings” (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism). In Japan, Confucian principles often inform and shape Buddhist and Shinto teachings and rituals. Confucian values of ancestor veneration influence both funeral rites and annual observances in remembrance of one’s kindred dead. Confucian virtues regarding learning and education are illustrated by Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines offering various charms, amulets, votive tablets, and good-luck pieces for educational success. Ian Reader and George J. Tanabe, Jr.’s Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan is a good example of this approach.2

Serious students were expected to be able to recite from memory hundreds of thousands of characters or thousands of pages of Confucian texts.

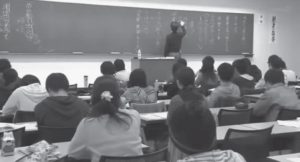

Emphasis on educational success is easily identifiable, and even quantifiable, within East Asia, where Confucian adherence is most pronounced. Confucian thought has dominated educational content and method for centuries. Before the development of modern colleges with liberal arts and sciences curricula, higher education and civil service entrance exams focused on, often exclusively, The Four Books of the Confucian Canon of The Great Learning, The Analects, The Doctrine of the Mean, and The Mencius, along with their associated commentaries and the Confucian Classics, which are often used as source material for analysis within The Four Books. The difficulty of these exams, along with the discipline and rigor necessary to prepare for them, has become legendary. “The student who sleeps three hours may pass, but the student who sleeps four will fail” was a common refrain. In the past, serious students were expected to be able to recite from memory hundreds of thousands of characters or thousands of pages of Confucian texts.

Students in Japan will spend 240 days in school each year, twelve weeks longer than in the United States.

The strict and severe expectations for student discipline continue today. Students in Japan will spend 240 days in school each year, twelve weeks longer than in the United States. Daily homework can exceed five hours, and school activities are often held on the weekends. As intense as the school schedule may be, it is often insufficient to prepare students for college entrance exams. Many students will attend an afternoon cram school or juku for entrance exams during high school. Because entrance exams can be so difficult, and such a high value is placed on getting into a good college, many students who do not pass annual entrance exams on their first try, will spend additional year(s) studying and attending cram schools preparing to take the exams again. These students are called ronin, a term previously used for samurai without a master and thus without position or place in society.

While living in Tokyo, I once met a nineteen-year-old who was still in high school. He was quite bright and not someone who you would expect to be held back. He was attending a Waseda preparatory high school which allowed for direct enrollment into Waseda University, one of Japan’s most prestigious private institutions of higher education. His mother calculated that she could have more influence and control over his studying at fourteen than at eighteen, and so he spent a ronin year after he didn’t pass the prep school’s entrance exam the first time after graduating from a public junior high school. This had become a common strategy at his high school and his graduating class had several members his age and even older.

It is not surprising that this intense culture of preparing for and taking college entrance is sometime referred to as juken jigoku, or entrance-exam hell. The high stakes of educational success engender stress and anxiety for students and their parents, who will often turn to religious rituals for assistance.

In Japan, contemporary interactions with Buddhism and Shinto often center on rituals for this-worldly benefits (genze riyaku). Temples and shrines provide rituals for increasing wealth, maintaining health, achieving longevity, building relationships, securing jobs, and defeating foes, among other needs and desires.3 Temples and shrines will often specialize in a type of genze riyaku with their enshrined Buddha or Shinto spirit (kami) holding exceptional power for a particular need. Guidebooks listing temples and shrines for specific benefits are published regularly.4 I once visited a very small Shinto shrine near Kuramae station in Tokyo which had gained notoriety for its rituals which were believed to be effective in finding lost pets.

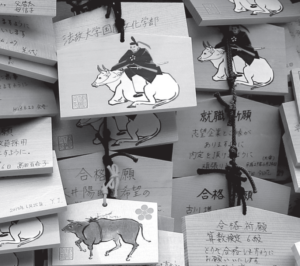

These rituals for specific benefits include material exchange with donations made for various ritual objects like amulets, charms, and votive tablets. These items are believed to be efficacious for evoking and ensuring desired blessings or benefits. Donations are almost always monetary, but offerings of different types are also common with food offerings being extremely prominent, especially rice and sake at Shinto shrines. For children, food ritual objects are also common. During the spring festival of setsubun beans are thrown at demons to dispel them. During the Shinto observance of shichi-go-san girls of three and seven years of age and boys of five years of age will receive a long stick of candy called chitose ame, or thousand-year sweets, for health and longevity. These Buddhist and Shinto ritual activities become particularly significant for providing additional support for educational success and many temples and shrines will provide various rituals and associated objects specifically for taking entrance exams. When teaching Confucian practices in Japan, it is common to focus on two central Confucian principles of ancestor veneration, with funeral rites being the primary practice, and the principle of learning being illustrated by traditions and rituals for educational success. It can be effective to include both approaches of showing how Confucian values are diffused in contemporary East Asian cultures, and also evidenced in the popular rituals found in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines.

Bunkyō ward of Tokyo, Japan. Source: Photo courtesy of the author

In the following classroom discussion outline, the popularity of the American candy Kit Kats in Japan can be used as an example of how Confucian principles are illustrated in modern religious rituals and cultural traditions. Japan is many things; the land of the rising sun, a land of harmony and group consciousness, a land of ultra-modern technology and urbanization, and Japan is also the land of many Kit Kats. Dozens of Kit Kat flavors have been released in Japan, far more than in any other country. Strawberry, citrus blend, cheesecake, hot chili, apple, green tea, sake, azuki bean sandwich, wasabi, and many, many more flavors can be found in Japan. Recently, several Kit Kat Chocolatory stores have opened in Tokyo and other metropolitan centers with decadently fancy Kit Kats being sold in impressively opulent boxes at a premium price. A visitor to Japan may eventually wonder why Japan seems to be obsessed with Kit Kats. The best answer may be because Kit Kats have become a ritual object for Confucian values in Japan; but to fully explain we need to go back over one thousand years in Japan’s history.

Today, arguably the most popular Tenjin shrine is Yushima Tenjin, just outside the main gates of Japan’s most prestigious University of Tokyo (Todai).

Ninth-century Japan was an extremely class and rank conscious society, especially for those in the imperial Heian court. For several centuries four families monopolized the top tier of imperial class and rank. To be born in one of these families guaranteed position, prestige, wealth, and power. Those who did not have the highest pedigree were often marginalized and disadvantaged with the top ranks of government status hopelessly out of reach. One person who climbed much higher than his pedigree was Sugawara no Michizane (845–903). Michizane was widely considered the genius of his age. His mastery of every subject, especially Chinese language and literature, was unmatched. Michizane was also seen as the ideal man of Japanese culture, a true Confucian sage. He became a close advisor to and staunch supporter of Emperor Uda (866–931/imperial reign 887–897).

Source: © Shutterstock. Photo by TK Kurikawa.

Source: Photo courtesy of the author.

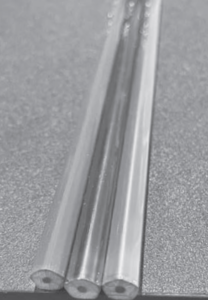

Upon Uda’s abdication, Michizane fell out of favor at court and was eventually banished. While the charges against Michizane’s were tenuous, his punishment was severe, and he was banished to the furthest imperial post on the outer islands of Kyushu. Ever the loyal subject and exemplar of Confucian ideals, the aged and ill Michizane made the long trip to Daizufu and died in exile. Calamity struck the court soon after Michizane’s death, with drought, fires, plagues, and the unexpected death of several sons within the clan responsible for his exile. As a form of appeasement, the court overturned his conviction, restored his rank and honors, and elevated his spirit to the Shinto Kami Tenman-Tenjin, enshrined at Kitano Tenmangu. Because of the scholarly reputation of Michizane, Tenjin quickly became a patron saint of education. Shrines to Tenjin proliferated and can be found throughout Japan, often close to major universities.5 Today, arguably the most popular Tenjin shrine is Yushima Tenjin, just outside the main gates of Japan’s most prestigious University of Tokyo (Todai). In keeping with Confucian tradition, university entrance is decided by a single entrance exam, often given from the school directly. Every spring, students come to take Todai’s entrance exam and with few exceptions, they will also stop by Yushima Tenjin to ask Michizane for supernatural assistance. There are many rituals available at Tenjin shrines, most central is the writing and posting of votive tablets called Ema, and thousands are posted at Yushima Tenjin every spring. Some of these Ema have pictures of Michizane in his courtesan robes printed on them. Many ritual objects for educational success emphasize a pun in Japanese language between the words gokaku or pentagon and gōkaku or educational success. Ema for passing exams will often have a pronounced pentagon shape and Tenjin shrines will often sell exam-taking pencils with five sides rather than the traditional six.

Source: Photo courtesy of the author.

certainly work out), keep smiling (in English), and daijōbu dayo (it will be OK).

Source: Photo courtesy of the author.

Students also participate in many rituals outside of Tenjin shrines and this brings us back to Kit Kats. In Japanese, Kit Kats are often spelled and pronounced as kitto katto. However, decades back they were alternatively spelled and pronounced as kitto katsu. While kitto katto does not hold much translated meaning in Japanese, kitto katsu, on the other hand, means “guaranteed win” or “absolute victory.” Anyone in Japan needing success may turn to Kit Kats during times of assessment or evaluation. For students taking entrance exams, in a Confucian-influenced country where education is so significantly stressed, Kit Kats have become a national obsession beyond any other imported candy. In the picture (left), you can see that this bag of Kit Kats has motivational sayings for test taking embossed on them.

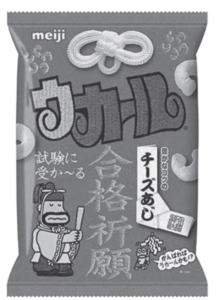

Special edition Ukaru chips are quite explicit in their claims for supernatural assistance in passing exams.

designed to look like an amulet received at a Shinto shrine.

Source: Photo courtesy of the author.

Perhaps the best example of a commercial product advertising its effectiveness for educational success comes from the Meiji corporation’s puffed corn snack, Karu chips. During the spring, Meiji adds an u to the front of Karu making the name of the chips the same as the Japanese verb to pass, especially used for passing an exam (ukaru). Special edition Ukaru chips are quite explicit in their claims for supernatural assistance in passing exams. The bag resembles an amulet one would receive at a Tenjin shrine with a white cord knot at the top and the words gōkaku kigan, or praying for educational success written down the center; on the left side is the Confucian sage Michizane praying for your kitto katsu. The popularity of Kit Kats in Japan can help us learn several things about Confucian practice in East Asian religions:

- At times of significant need, many people in modern Japan, and other countries in East Asia, will turn to religious rituals available at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. The Confucian principle of educational success is so consistently stressed in East Asia that exam taking becomes one of the highest times of significant need.

- Confucian principles are put into practice in East Asia through religious rituals found in Buddhism or Shinto, and also through various cultural traditions outside of institutional religious practice. The Confucian virtues of ancestor veneration can be found in funeral rites, and the Confucian value placed on learning can be seen in rituals for educational success.

- Often the lines between cultural traditions and religious rituals are blurred, which can make Confucian practices more complicated and implicit, but no less significant.

Teaching ideas

- Depending on class size, the teacher might want to bring in a bag of Kit Kats in a different Special edition flavors are more common in the US and Japanese Kit Kat flavors can often be found in Asian markets.

- The teacher may want to ask their students if they have rituals or traditions for educational The discussion can focus on why these rituals or traditions perpetuate and how they are perceived as effective. Often students do not have the same level of participation in rituals for educational success as students in Japan, or other places in East Asia, and this can lead to a discussion of risk/reward and the motivations for modern individuals to participate in religious rituals.

- The link between Kit Kats and Shinto rituals at Tenjin shrines can illustrate connections between religion and culture facilitating a discussion on how religion can influence cultural traditions or civic customs. Discussions could include the materialism around historic religious observances like Halloween, Valentine’s Day, or Christmas and the values that may underpin the observances.

NOTES

- R. Reid, Confucius Lives Next Door: What Living in the East Teaches Us About Living in the West, (New York: Vintage Books, 2000).

- Ian Reader and George J. Tanabe, Jr., Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religions of Japan, (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1998).

- , 37.

- See Nakazawa Toshiaki, Edo Tokyo Go-Riyaku Jiken (Tokyo: Kasamashoin, 2021).

- Ivan Morris, Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan (New York: Holt Reinhart and Winston, 1975).