As Kiyoshi Kurosawa returns home from the Venice Film Festival with a heavy suitcase, AnOther looks back on some career highlights that forged his winning path

“Master of horror” is not traditionally an accolade recognised by the world’s leading film competitions, but for Kiyoshi Kurosawa, it’s proved something of a boon.

Ever since finding himself in the unique position of having a different film screening at each of Berlin, Cannes and Venice in 1999 (for License to Live, Charisma and Barren Illusion respectively), he’s gone from strength to strength on the film festival circuit. And on September 13 this year he might have scored his biggest win yet. Taking home the Silver Lion for Best Director at Venice for new historical thriller Wife of a Spy, Kurosawa now adds the coveted award to a trophy cabinet already well-stocked with prizes from Cannes, Chicago and the Japanese Academy Film Awards. Few could argue with those credentials.

Modelling his early films on the works of John Cassavetes, Alfred Hitchcock and John Carpenter, Kurosawa would become known in the late 1990s for a palpable sense of foreboding in a series of genre-defying crime and horror features. Elevating himself from a fledgling career in pink films and straight-to-video schlock, his tense camerawork and methodical pacing in these films transformed simple mystery narratives in something much eerier and more thought-provoking. Imbuing his films with a lingering sense of unease, minimal works like Cure and Pulse would become cult classics of Y2K Japanese cinema, as their nuanced explorations of the vulnerabilities of the human condition resonated with audiences at home and abroad.

While working less regularly in crime and horror genre since the late 2000s (2013’s fan favourite Creepy notwithstanding), Kurosawa has, in recent years, maximised his appeal in the eyes of critics by applying his meticulous craft to family dramas and philosophical romance works. But it’s the golden years that remain Kurosawa’s most memorable, and as the director returns home from the first major film festival to go ahead since Covid-19 with a heavy suitcase, AnOther looks back on some career highlights that forged his winning path.

Sweet Home, 1989

For a director later revered for his mastery of brooding chills, Kurosawa’s first real project of note is something of a curiosity. A cliche-laden horror B movie that harks back to 1960s classics like The Haunting, Sweet Home is a formulaic and predictable, but nonetheless enjoyable yarn about a haunted house in the middle of a foggy forest. Stylistically, it bears little in common with Kurosawa’s later masterworks, but the spectacular special effects by The Exorcist make-up designer Dick Smith – whose flesh-melting physical effects and monstrous ghouls remain impressive to this day – make it a hoot.

What makes Sweet Home genuinely noteworthy, though, is its unlikely legacy. Produced in conjunction with a video-game tie-in of the same name (also supervised by Kurosawa), Sweet Home would ultimately provide the foundation for one of the most influential video games of the mid-1990s. The original Resident Evil, a PlayStation original that sold over 2.75 million units upon release in 1996, was a direct remake of the original Sweet Home adaption, with the game’s Spencer Mansion setting among many recycled elements inspired directly by Kurosawa’s production.

Cure, 1997

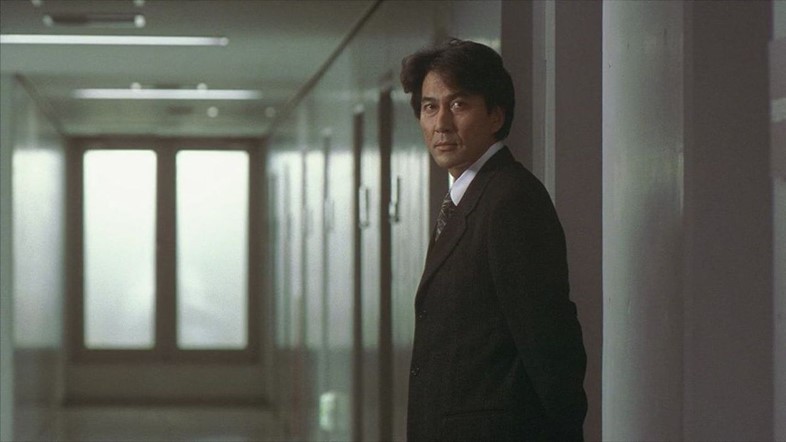

Refining his directorial style in the early 1990s in Japan’s straight-to-video ‘V-cinema’ sector, Kurosawa would, in 1997, release his mainstream breakthrough Cure. A dark detective procedural also penned by the director, it won lead actor Koji Yakusho (a Kurosawa mainstay) the Best Actor award at the Tokyo International Film Festival that year, and a nomination for Best Director for the man behind the camera, too.

Cited by Parasite director Bong Joon-ho as one of the greatest films of all time in 2012, this eerie drama examines a series of copycat murders committed by perpetrators who have no recollection of their motive. Channelling the grim noir elements of Seven while also featuring a complex villain à la Silence of the Lambs, Cure’s unsettling allure grows as the arcs of the protagonist and antagonist become fatefully entwined.

Shot using slow, minimal long takes and bereft of any musical score other than vague and ominous rumblings, Cure evokes a constant sense of breath-holding as it builds a hypnotic atmosphere. As it reaches its gloomy climax, using muted colours to evoke the image of faded photographs and foggy memories, this Lynchian fever dream begins to feel more and more like a nightmare.

Serpent’s Path, 1997

Shot back-to-back with Eyes of the Spider over two weeks, this low-budget curio shares both leading actor and premise with its sibling counterpart, as Sho Aikawa (Gozu, Dead or Alive) twice seeks revenge on the perpetrator of a heinous child murder. The difference in tone, story and structure ensures two markedly different films, though, and it is Serpent’s Path’s puzzle-like dual narrative that offers an extra layer of intrigue, as a series of possibly innocent men find themselves chained up in an abandoned warehouse.

Kurosawa’s unique composition amplifies the element of mystery in this lean, 80-minute head-scratcher, as wandering long takes traverse both foreground and background in a series of intricate scenes, almost like a play. Stellar cinematography helps to brighten up this largely grey picture, but ultimately the film’s violent sleuths’ attempts to unravel an increasingly odd mystery leads them to a progressively dark mental space.

Pulse, 2001

In 1998, Hideo Nakata’s Ring made audiences across the globe terrified of their own TV sets. Three years later, Kurosawa’s Pulse made people fear the sound of their internet dial-up connection.

Technophobia was rife at the turn of the century, as widespread hysteria over a “millennium bug” that would cause havoc to global computer systems dominated the news. It all turned out to be a load of hodgepodge in the end, but Kurosawa captured the paranoia with aplomb in this haunting tale of a ghostly invasion through the medium of personal computers.

Kurosawa’s most unnerving work is a masterpiece of existential terror, building towards an apocalyptic conclusion where the primary fear is not death, but the possibility of an eternal, purgatorial afterlife built upon loneliness and desolation. Elevated by a soundtrack that recalls the horror-mysteries of Alfred Hitchcock, and utilising shadowy and colour-drained cinematography, Pulse offers a vision of a doomed universe with little hope for salvation.

Tokyo Sonata, 2008

In the 1950s, Yasujiro Ozu captured the minds of audiences with his intimate “home drama” films, which portrayed a tender, idealistic version of traditional Japanese family values. With their intricate shot arrangements and gentle pacing, films like Tokyo Story would go on to be considered some of the greatest of all time.

Kurosawa’s Tokyo Sonata takes the tropes and themes of Ozu’s masterworks and places them in modern Japan with startling effect. The peace of the homestead is juxtaposed with a noisy office space during the opening scenes, as the patriarch of the Sasaki family is let go from his senior managerial position. As the film observes the changing values in Japanese society, Sasaki hides his shame from his family, continuing to dress in a suit, leaving for “work” each morning, and returning each day feigning exhaustion, heading straight to bed. All the while, his oldest son yearns to join the US Army so that he can “protect” his family in a way that his father was unable to, while his younger sibling dreams of learning to play the piano – a wish denied by his father.

The dining table, a metaphor for community in Ozu’s work, remains central to Kurosawa’s Un Certain Regard-winning deconstruction. But in Tokyo Sonata, this powerful symbol is continuously obscured by crockery, shelves and stair bannisters, while a noisy train repeatedly races past the window. It’s a potent statement about the changing state of the world, but when the film arrives at its stirring conclusion, scored by a captivating rendition of Debussy’s Clair de Lune, the viewer is reminded that there is harmony to be found between the old ways and the new.