A guest post on Miklós Bánffy by Scott of the seraillon blog

I feel odd to be writing, for a site entitled “Writers No One Reads,” about a writer whose works people actually do read – at least when they can find them. Overcoming that obstacle has become easier with publication this summer of an Everyman’s Library edition of Count Miklós Bánffy’s “Transylvanian Trilogy“ of novels: They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided. Bánffy’s work – published in Budapest in the late 1930s but released in English only a dozen years ago (by Arcadia Books, in a run that quickly went out of print) – should now emerge from its cult following to recognition as one of the great works of the last century.

That it has taken so long for the trilogy to reach this point is a story in itself. After initial publication, the books were eclipsed by war and politics. Bánffy – a politician, cultural leader, and foreign minister of Hungary, denounced by the Nazis and out of favor with the postwar communist government as well – found his books ignored. Soviet dominance of Hungary ensured that they all but vanished. Only in 1982, as communism began to crumble, was the first volume republished, partly to offer insight into the historical roots of the contemporary political situation. The other volumes followed in the early 1990s to great acclaim.

Were it not for fortuitous circumstances, the novels might have remained little known outside of Hungary. Translator Patrick Thursfield, in his preface to the Arcadia edition, recounts learning about them by chance from his neighbor in Tangiers, Bánffy’s daughter Katalin Bánffy-Jelin, who had begun an English translation consisting of loosely bound pages partially mangled by her cat. A collaboration began, and the resulting publication, with a foreword by Patrick Leigh Fermor, won the 2002 Oxford-Weidenfeld prize and accolades from around the world. Unfortunately, the books’ scarcity kept them from wide readership.

As almost anyone who has read the trilogy will attest, the work presents an enthralling, hauntingly lucid panorama of an empire in decline. The three volumes – their titles taken from the warning lines that miraculously appear on a wall during the feast of Belshazzar in the Old Testament – are set largely in Budapest and the Transylvanian city of Kolozsvár between 1904 and 1914, and trace the fates of Count Balint Abady and his dissolute cousin Laszlo as Austria-Hungary ignores “the writing on the wall” and lapses into political mismanagement, corruption, pettiness, and abandonment of the principle of noblesse oblige that had governed class relations in a society late to emerge from feudalism.

With unusual clarity and occasionally scathing humor, Bánffy relates the commitment – or lack thereof – of those who were well-off towards those who were not. The trilogy’s depictions of the machinations of politics – both legislative processes and the nuanced array of mechanisms that maintain class and power – stand out as exceptional. A skillful sense of how to orchestrate a scene to evoke its political and social significances pervades the trilogy, a talent likely picked up by Bánffy during his work in theater and as a director of state political pageantry.

Through Balint Abady, Bánffy portrays the rare politician who accepts his privileges as part of a social contract that binds him to the rest of society. Abady represents a model of restrained indignation concerning the abuses of power, the laxity of the rich, and the failure to recognize the fragility of the nation’s assets: its political and cultural institutions, irreplaceable natural resources, and diverse peoples. With wisdom and compassion, Abady decries the decadence of his own short-sighted class while displaying keen understanding of the problems of the poor, the conditions of the lives of women (on issues of gender and sexuality, Bánffy shows disdain for conventions that restrict the independence of women), and the destructive prejudices directed towards gypsies, Jews, and the Romanians who work Transylvania’s forest holdings. Through Abady’s recurring visits to these woodlands, Bánffy conveys a profoundly atmospheric appreciation for these enchanting, priceless wildernesses, the descriptions of which stand out as one of the trilogy’s star attractions.

But it is the work’s modernity and immediacy that may resonate most strongly with contemporary readers. Bánffy’s far-sightedness communicates conflicts manifest in the modern world – not so much because he treats of universal themes as because he lances familiar political and social dynamics anathema to the survival of a culture: an emphasis on short-term profiteering and exploitation of resources; fractious, tribalist squabbles; the paralyzing self-interest of legislatures; an immersion in frivolous pursuits while serious ones are ignored; blind confidence that the good life for some, gained at others’ expense, will continue without consequence.

With this new edition, a literary event to celebrate, Miklós Bánffy’s Transylvanian Trilogy will hopefully achieve the wide readership it so richly deserves. The new edition, while unfortunately omitting Thursfield’s preface and Fermor’s foreword, offers compensation through a new introduction from Hugh Thomas that provides critical biographical and historical information previously lacking, a chronology of Bánffy’s life, a genealogy of Bánffy’s family, and helpful maps. Those new to this work will likely find a masterful testimonial to one of the most significant and premonitory collapses of political power in the 20th century (The Guardian recently ranked the Transylvanian Trilogy among the ten best books – fiction or non-fiction – about the Austro-Hungarian empire). They may also find, as in those startling ancient Greco-Egyptian funerary portraits of Fayum, a surprisingly recognizable world staring out at them from across the years with an enrapturing immediacy and a frank, beseeching clarity that looks to the future and asks: And you?

***

Editor’s note: Discover many more neglected books at Scott’s blog seraillon

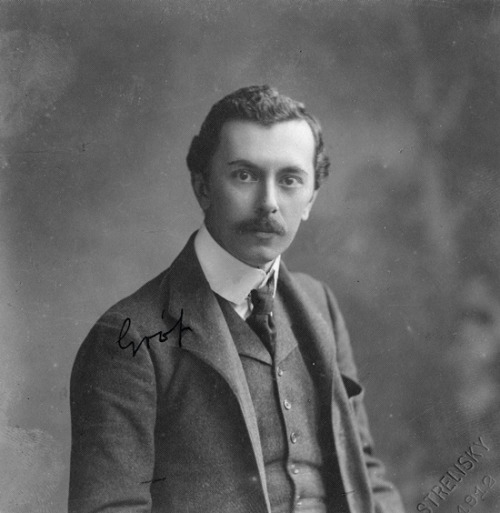

Photography of Banffy via

88 notesShowHide

white-polkadot liked this

decayke liked this

thislittlekumquat liked this

thislittlekumquat liked this ocaputbrook1971 liked this

of-cannibals-and-kings reblogged this from writersnoonereads

of-cannibals-and-kings liked this

i-roaring-girl liked this

elijahkinchspector liked this

ulteriorfirmament liked this

alicestowe1914 reblogged this from heavyanddissolved

busarewski liked this

duorma92 liked this

duorma92 liked this  horsesandtigers liked this

horsesandtigers liked this stuffworthlivingfor liked this

kukashkin reblogged this from heavyanddissolved

kukashkin reblogged this from heavyanddissolved urihu liked this

bzanetti liked this

parmandil reblogged this from heavyanddissolved

heavyanddissolved reblogged this from writersnoonereads and added:

just finished this magnificent trilogy which I’ve deliberately slowly been digesting for the last six months - a real...

leyanabuz reblogged this from writersnoonereads

delusyum reblogged this from writersnoonereads

delusyum liked this

piltdownlad liked this

handsomeyoungwriters reblogged this from writersnoonereads

bookstorey liked this

da-kadmeister liked this

g8gway liked this

etterem-kritika liked this

rlreevesjr liked this

bazaardvark liked this

baudelairies liked this

irkallia liked this

dikalabulanbermainbiola liked this

ambatkins liked this

ambatkins liked this westfalleast liked this

citylightscomebackinjune reblogged this from writersnoonereads

aj-at-woo liked this

sisyfos liked this

lishsterical liked this

macavety liked this

ratazzana liked this

washedawaybyrain liked this

tredynasdays liked this

writersnoonereads posted this

- Show more notes