This weekend is the Destinations Travel Show at Earl’s Court. I’m on so many mailing lists for various travel agencies that I ended up with four free tickets for it, so I went yesterday.

A travel show is a strange thing. First off, the word ‘show’ is completely inappropriate; there was a stage at the back with various national dances going on but that was at the margins of the event. The main experience is that of flitting from stall to stall, collecting brochures and talking to reps. The aim is reportedly to provide the opportunity for people to discover new places, broaden their holidaying horizons, etc., but I think the underlying reason is what I call ‘far-flungerie’.

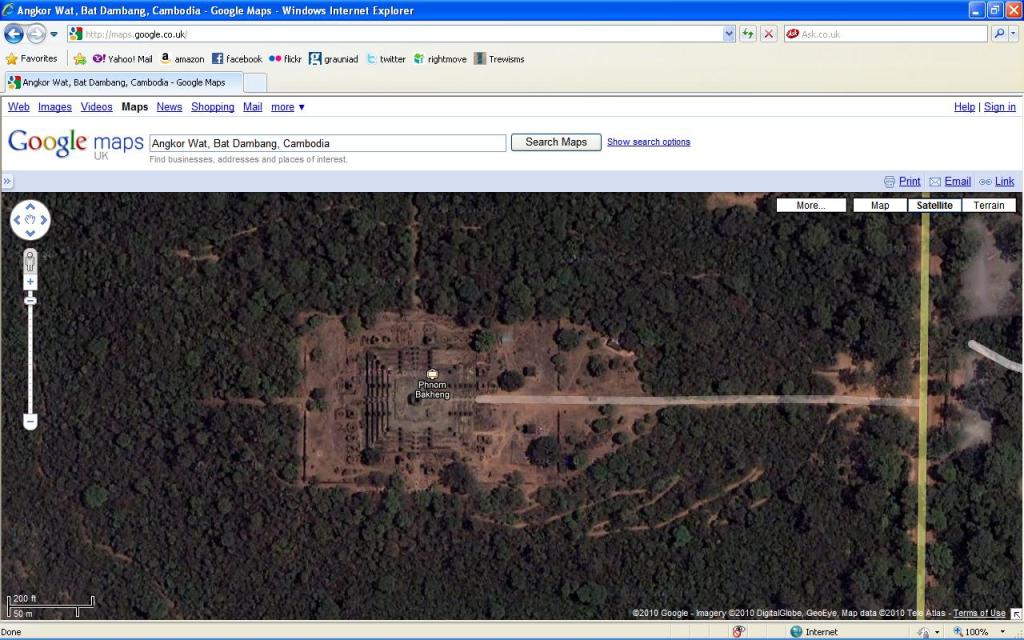

In the 2006 edition of The Traveller’s Handbook Devla Murphy mentions an imaginary country, Far Flungery, a place “where nobody within 200 miles speaks a syllable of any European language” (p. 18). The country of Far Flungery represents a destination for the traveller who seeks, above all else, difference: a cultural as well as a physical distance from everyday life. However, to me, this phrase has become an occupation, which I spell ‘far-flungerie’; it’s like armchair travel, but slightly less passive. Far-flungerie is detailed planning of trips, as well as reading about other people’s travels. The internet is an enormous boon: sites like The Man In Seat 61 or Trip Advisor can soak up hours of speculative far-flungerie. Sometimes these plans are in earnest, and sometimes they are just thought-experiments: how long would it take to get from London to India by train? Can you cross the Atlantic on a tall ship? What route would I take if I drove across America? Google Maps is also fantastic for this: try zooming in on the satellite view of Samarkand or Ankhor Wat.

The most extreme form of far-flungerie I have ever come across is in my favourite trilogy, Miklos Banffy’s ‘The Writing on the Wall’. In book 3, ‘They Were Divided’, Balint Abady comes across his friend Farkas Alvinczy at home:

After more somewhat desultory talk between them Farkas finally spoke of the map that covered the table and which had been carefully attached to it by metal clips. It represented the Indian Ocean, from Aden to the Malacca Straits. When Balint asked why he was studying this map Farkas for the first time became quite animated and eloquent.

‘That is where I’m travelling at present! You see? Today my ship arrived here!’ […] He pointed to a steel pen head which had been placed on the blue coloured sea, pointing to Ceylon at the foot of the pink-coloured sub-continent of India. ‘This pen here, that is my ship. Every day I push it forward the distance travelled in the previous twenty-four hours, according to this book. The day before yesterday we left Bombay, and tomorrow we shall arrive at Colombo.’

He told how he had travelled like this for the last two years. He had ordered accounts of voyages and the corresponding maps, and each day he read just as much as was covered by that day – no more, for that would be cheating. Like this it was just as if he were making the voyage himself. If the traveller wrote that he had spent five days at sea with nothing to relate, then Farkas waited five days before reading on or marking the map.

‘But isn’t that rather dull, making yourself wait five days?’

‘Not at all! Time goes by. Sometimes faster than you’d imagine. I think about the sea and about my travelling companions. I dress for dinner in the evenings – you always do on a luxury liner, you know.’

He told Balint he was now a much-travelled man. The previous year he had rounded Cape Horn, visited Terra del Fuego and indeed ‘done’ South America. He had also been to the South Pole and back. It had been beautiful and most interesting even though it had been a shorter trip that he really liked.

‘This one is very good. The weather’s lovely and so far the sea has been quite calm!’

Balint looked hard at Alvinczy wondering if he was making fun of him and was just saying all this for a joke, but it was clear he meant everything he said and took it all very seriously. […] [‘They Were Divided’ Arcadia 2003, p. 287-288]

This of course is far beyond the borders of the eccentric, but harmlessly so. A slightly more rational form of this occupation is, I imagine, taking place throughout London at the moment by people like me who, stocked up with holiday brochures, are happily studying the suggested itineries of far-flung trips, half with the intention of going in the future and half, like Farkas, with the intention of travelling right now in our minds.

One thought on “Far-Flungerie”