To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot: Portraits of the Artist.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2017/08/15/james-tissot-portraits-of-the-artist/. <Date viewed.>

We know so little of James Tissot (1836 – 1902) outside of his work; his personal papers were destroyed, and he had no disciples to carry on and burnish his reputation.

We know so little of James Tissot (1836 – 1902) outside of his work; his personal papers were destroyed, and he had no disciples to carry on and burnish his reputation.

But there are several photographs of him, and his self-portraits.

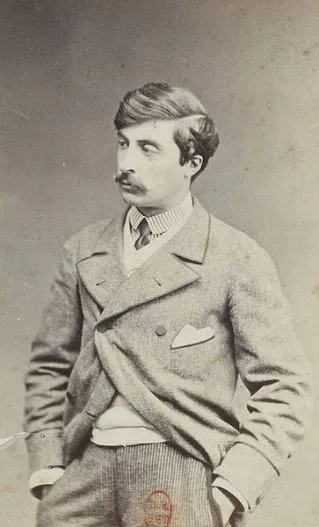

This photograph, made by Robert Jefferson Bingham (1825 – 1870), was made shortly after Tissot arrived in Paris, in 1855 at age 19.

Bingham, an English photographer, showed nineteen photographs at The Great Exhibition of 1851, and also made photographs of the Exposition Universelle of 1855 in Paris. In 1857, Bingham moved to Paris and opened an atelier in the artistic quarter of Nouvelle Athènes. So it is likely that Tissot was 20 or 21 in this photo, a dapper and ambitious young art student from the provinces quickly establishing himself in the competitive art world of the capital. He appears considerably more sophisticated than he presents himself in a self-portrait as a monk a few years later, c. 1859.

A photograph of James Tissot was made about 1865 by Étienne Carjat (1828 –1906), a French journalist, caricaturist and photographer who co-founded the magazine Le Diogène and founded the review Le Boulevard. But Carjat is best known for his numerous portraits and caricatures of Parisian political, literary and artistic figures. In 1860, he opened a photography studio at 56 rue Laffitte, which he operated for 20 years. Carjat received a medal for his photographs in the Salon of 1863. While he did not achieve the fame of Nadar, he did capture the personalities of his sitters, who included Gioacchino Rossini, Alexandre Dumas (père), Emile Zola, Charles Baudelaire, Sarah Bernhardt, Gustave Courbet and Victor Hugo. Carjat was a friend of Henri Fantin-Latour, and it was probably through him that he met James McNeill Whistler in Paris in April 1863. Around 1865, Carjat made two cartes-de-visite photographs of Whistler, who had been friends with Tissot since about 1857.

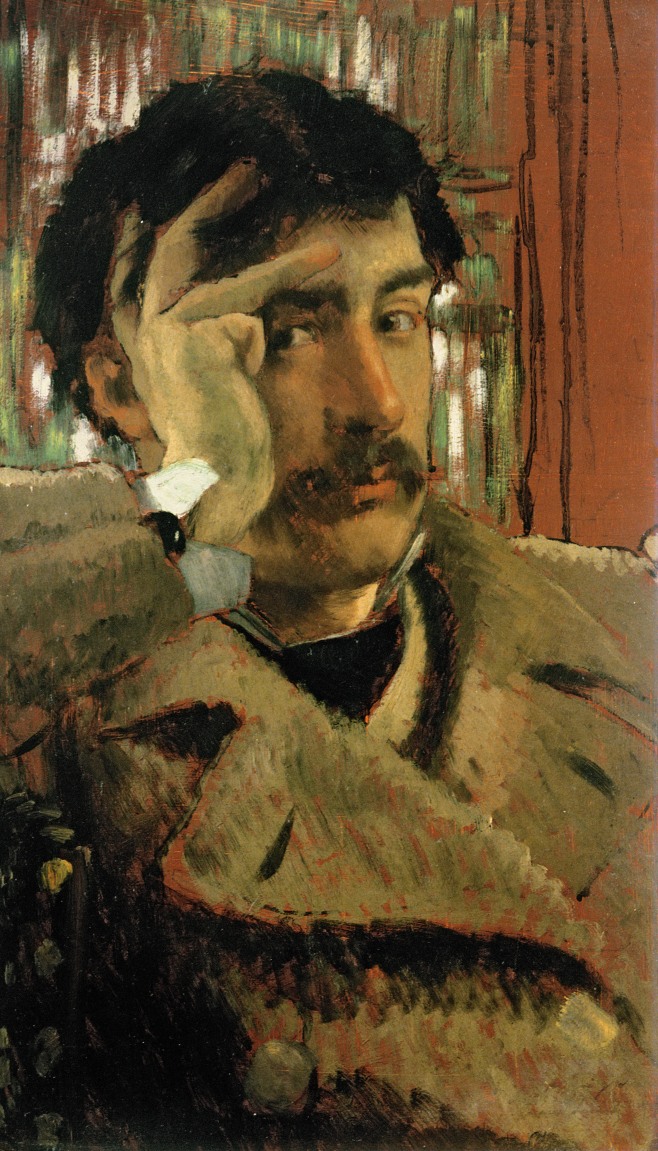

In Carjat’s photograph, Tissot is about 29 years old. He was earning 70,000 francs a year as an easel painter, and he produced another self-portrait at this time.

Self portrait (1865), by James Tissot, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA, USA. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, by Lucy Paquette © 2012

At the Paris Salon in 1866, Tissot was elected hors concours: from then on, he could exhibit any painting he wished at the annual Salon without first submitting his work to the jury’s scrutiny. The price for his pictures skyrocketed. At 30, he decided to purchase property on the most prestigious new thoroughfare in Paris, the avenue de l’Impèratrice (Empress Avenue, now avenue Foch). By late 1867 or early 1868, Tissot was living in grand style in his luxurious new villa.

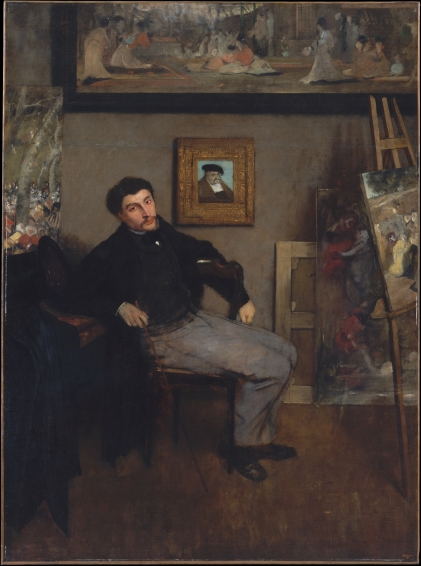

In 1867-68, Tissot’s friend Edgar Degas painted him, and this detail from a carte-de-visite photograph reflects his appearance at the time. Tissot was described as having “a shock of jet-black hair, a drooping Mongolian mustache, an excellent tailor, and a small private fortune.”

Portrait of James Jacques Joseph Tissot (c. 1867-68), by Edgar Degas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1939. (Photo: Open Access).

After winning the right – at age 30 – to exhibit anything he wished at the Salons, and busy with commissions from his aristocratic patrons, Tissot did not need to kowtow to the critics. He began painting light-hearted, sexually suggestive pictures, which would have been shocking in a contemporary context. He safely set them in the years of the French Directory (1795 to 1799), as if they depicted behaviors of a bygone time. One critic at the time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.” Tissot, having made his own way to the top of his profession, probably was a little smug in his success.

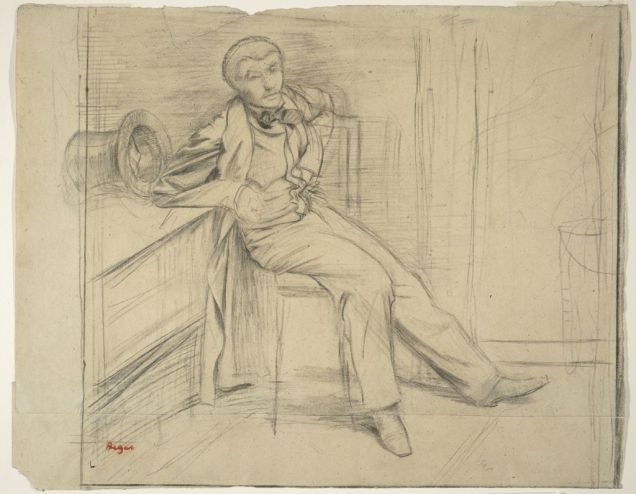

Study for James Jacques Joseph Tissot (c. 1867-68), by Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas. Prepared chalk on tan wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Cesar M. de Hauke. (Photo: Open Access)

When the Second Empire collapsed on September 2, 1870, Tissot’s charmed life in Paris ended. He became a sharpshooter, defending Paris in an elite unit, the Tirailleurs of the Seine. [See James Tissot and The Artists’ Brigade, 1870-71.] In the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War – the bloody Commune in mid-1871 – James Tissot fled Paris with 100 francs to his name, establishing himself in the competitive London art market by catering to the British taste. By 1873, he bought the lease on a spacious villa in St. John’s Wood, soon building an extension with a studio and huge conservatory.

He declined Degas’s exhortation to show his work in Paris with the independent group of French artists who organized their first of eight exhibitions in Paris in 1874 and who soon became known as Impressionists. But Tissot and Edouard Manet travelled to Venice together in the fall of 1874, and Tissot bought Manet’s Blue Venice on March 24, 1875 for 2,500 francs. Manet badly needed the income. Tissot hung the painting in his home in St. John’s Wood, London, and tried to interest English dealers in Manet’s work. [For more on how Tissot tried to help his friends, see James Tissot the Collector: His works by Degas, Manet & Pissarro.]

A few of his contemporaries described him at this time. Berthe Morisot, in an 1875 letter to her sister, Edma Pontillon, wrote, “We went to see Tissot, who does very pretty things that he sells at high prices; he is living like a king. We dined there. He is very nice, a very good fellow, though a little vulgar. We are on the best of terms; I paid him many compliments, and he really deserves them.” During the same trip, Morisot wrote to her mother, “[Tissot] is turning out excellent pictures. He sells for as much as 300,000 francs at a time. What do you think of his success in London? He was very amiable, and complimented me although he has probably never seen any of my work.”

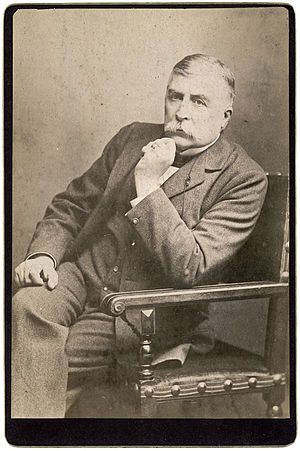

Francis, Duke of Teck (1837 – 1900)

The same year, painter Giuseppe De Nittis wrote to his wife, Léontine, “I saw Tissot at the club, he was very nice, very friendly.”

Alan S. Cole wrote in his diary, on November 16, 1875, “Dined with Jimmy [Whistler]: Tissot, A[lbert] Moore and Captain Crabb. Lovely blue and white china – and capital small dinner. General conversation and ideas on art unfettered by principles.”

British painter Louise Jopling (1843 – 1933) wrote, “James Tissot was a charming man, very handsome, extraordinarily like the Duke [then, Prince] of Teck. He was always well groomed, and had nothing of artistic carelessness either in his dress or demeanor…he was very hospitable, and delightful were the dinners he gave.”

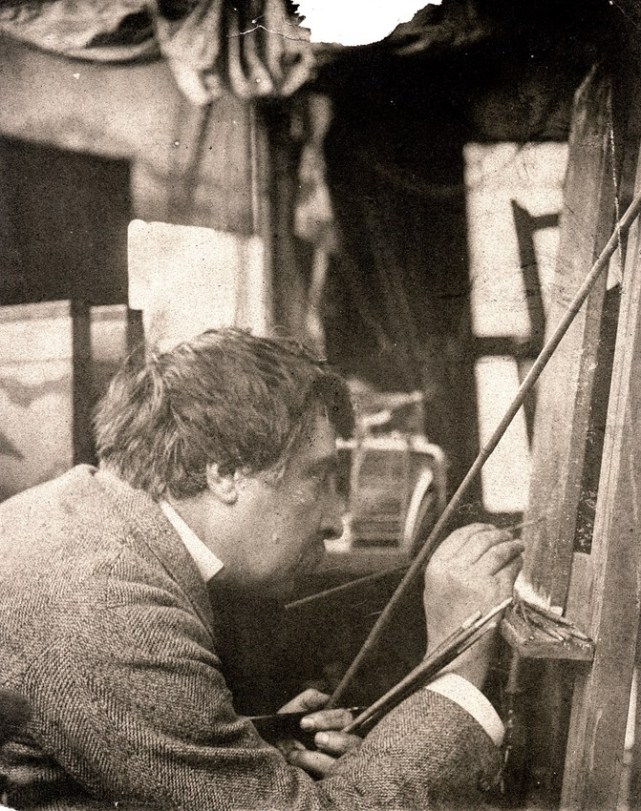

By 1876, James Tissot again had earned great wealth and lived in relative seclusion for six years with his mistress and muse, young divorcée Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly Newton (1854 – 1882). [See James Tissot Domesticated and James Tissot’s Model and Muse, Kathleen Newton.] In this photograph, Tissot is in his forties, painting in his studio. French writer and critic Edmond de Goncourt (1822 – 1896) described him as having “a large, unintelligent skull and the eyes of a boiled fish.” It was in late 1874 that Goncourt wrote in his journal, “Tissot, that plagiarist painter, has had the greatest success in England. Was it not his idea, this ingenious exploiter of English idiocy, to have a studio with a waiting room, where, at all times, there is iced champagne at the disposal of visitors, and around the studio, a garden where, all day long, one can see a footman in silk stockings brushing and shining the shrubbery leaves?” Nevertheless, Goncourt relied on Tissot to illustrate Renée Mauperin, a novel written with his brother Jules (published in 1884). Kathleen Newton modeled for the heroine.

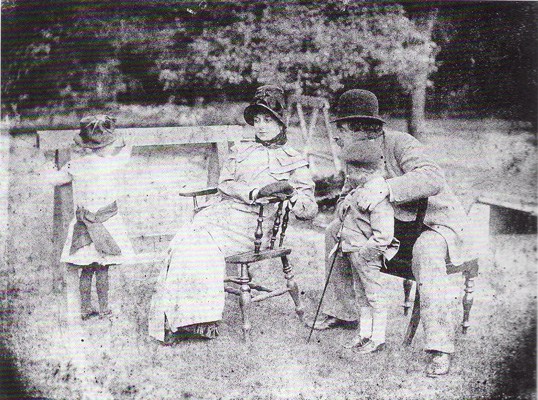

In the photograph below, Tissot poses for Waiting for the Ferry (c. 1878) in his garden at Grove End Road with Kathleen Newton and her children, Muriel Violet Newton and Cecil Newton.

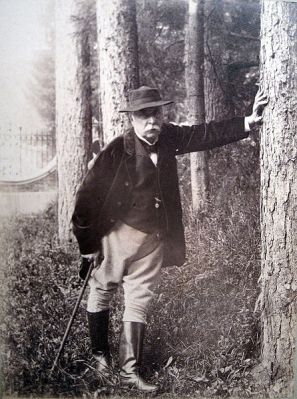

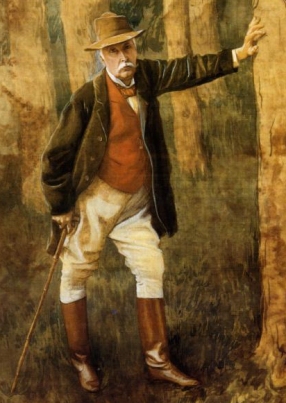

Kathleen Newton died of tuberculosis at Tissot’s St. John’s Wood home in November, 1882, and he immediately moved back to his Paris villa. He tried, and failed, to recapture his early success before embarking on an ambitious new project. In 1885-86, he made his first trip to Palestine to research his illustrated Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. In the above photograph, taken in 1898, Tissot was sixty-two. His self-portrait in watercolor, below, was painted somewhat earlier.

Portrait of the Pilgrim (1886-1896), by James Tissot. Self-portrait in watercolor and graphite. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

In 1896, Tissot exhibited his complete Life of Christ series in London. His La Vie de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ was published in France, with the artist receiving a million francs for reproduction rights.

He embarked on his third trip to Palestine to begin an illustrated Old Testament (which would be published in 1904, two years after his death). On the ship, English artist George Percy Jacomb-Hood (1857-1929) encountered Tissot and found him “a very neatly dressed, elegant figure, with a grey military moustache and beard, [who] always appeared on deck gloved and groomed as if for the boulevard.”

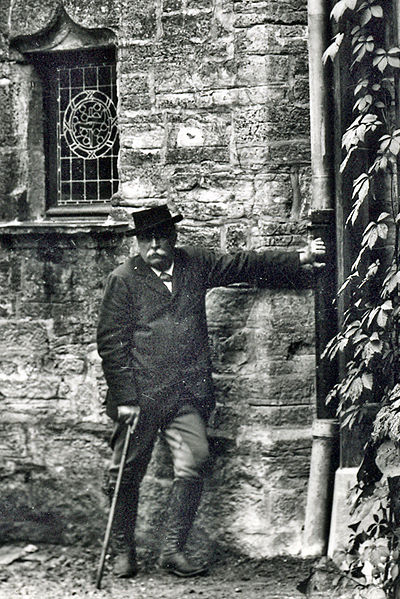

James Tissot’s father died in 1888, leaving him the Château de Buillon, near Besançon in eastern France. During his remaining years, he lived partly in Paris and partly at the Château, improving the building and grounds. The photograph above was made of Tissot around 1898. He must have been experimenting with poses for his self-portrait of that year (below, right).

James Tissot died in 1902, at age 66, extremely wealthy and renowned for what was considered his great masterpiece, The Life of Christ illustrations. In his obituary in The Evening Post, Tissot was compared to William Blake, though “uniting as Blake never did, and as no other prominent artist has done, the mystical and ideal with an intense realism.”

An early biographer who knew him briefly, Georges Bastard (1881 – 1939), wrote that Tissot “was as reserved as the cut of his coat.” No bon mots have been recorded, nor anecdotes by contemporaries who may have encountered Tissot at Second Empire receptions or balls – just a bit of jealous carping about his success. While certainly not a reticent man, James Tissot could not have been a gregarious one. He was determined to succeed on his own terms, and he did. His work continues to fascinate us, and it alone must speak for him.

Related posts:

A James Tissot Chronology, by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web

James Tissot (1836-1902): a brief biography by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web

James Tissot the Collector: His works by Degas, Manet & Pissarro

Was James Tissot a Plagiarist?

© 2017 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

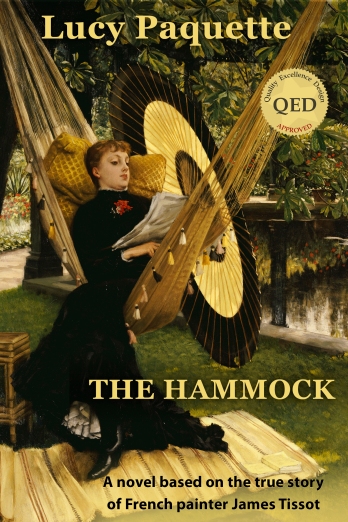

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.