Biography

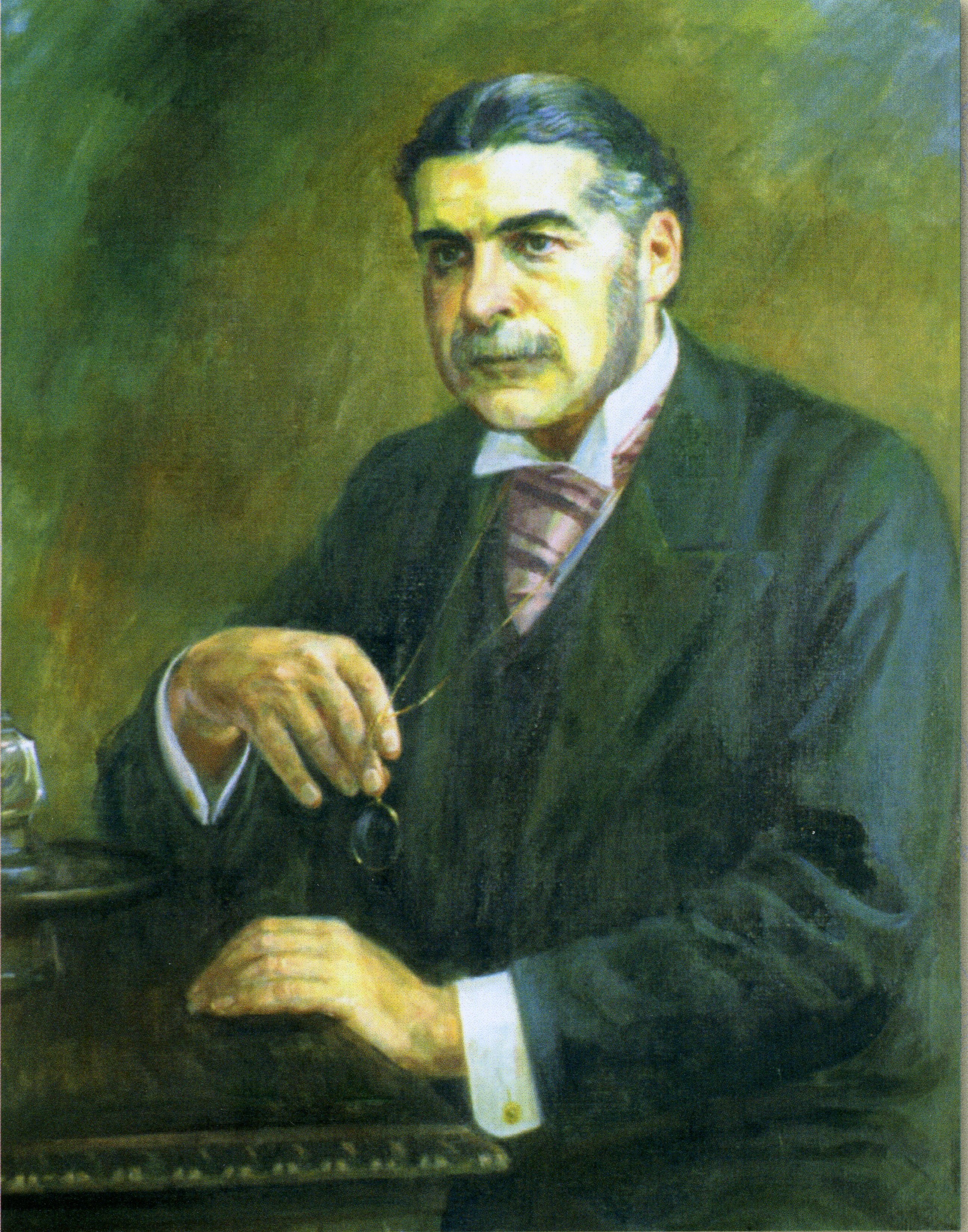

Arthur Seymour Sullivan was born in London on 13 May 1842, the second son of Thomas Sullivan (1805–1866) and Mary Clementina Sullivan, née Coghlan (1811– 82). He evinced prodigious musical talent from a very early age: his father was a theatre musician who became an army bandmaster with the result that Arthur could play every instrument in the military band by the age of eight. No career other than music was ever an option, and in April 1854 he was accepted, though at nearly twelve he was well over the customary age, as one of the Children (choristers) of the Chapel Royal. Here he came under the tutelage of the Revd. Thomas Helmore (1811–1890), a formidable teacher and scholar, and quickly became a favourite choice when solos were required. He also took his first steps as a composer, most notably in 1855 with the publication of a sacred song, O Israel. In the summer of 1856 Sullivan, despite being the youngest entrant, won the competition for the first Mendelssohn Scholarship. This enabled him to study at the Royal Academy of Music, where his tutors included Sir William Sterndale Bennett (1816–75) and Sir John Goss (1800–80), and then from 1858 at the Conservatory in Leipzig, at that time the finest musical training school in the world. Here he learned from the best teachers in Europe, including Ignaz Moscheles (1794–1870), Moritz Hauptmann (1792–1868), Julius Rietz (1812– 77) and Louis Plaidy (1810–74).

Sullivan left Leipzig in April 1861 after a successful performance of his final examination piece, a set of incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Back in London he took work as a church organist (initially at the fashionable St. Michael’s, Chester Square, not far from Victoria station) and taught to earn his living. In April 1862 The Tempest was performed at one of the celebrated Crystal Palace Saturday concerts conducted by August Manns (1825–1907). It was an immediate and enormous success, so much so that a repeat performance had to be given the following week. This second performance was highly praised by Charles Dickens. It is no exaggeration to say that Sullivan became famous overnight.

Fame, however, does not pay the bills, and he continued to take whatever work came along. He played the organ, conducted and taught, eventually becoming the first Principal of the National Training School for Music (now the Royal College of Music). He edited two hymnals and vocal scores of a number of standard operatic works. He also composed many songs and hymns, the royalties from which provided him with a steady income in the 1860s and 70s. He was appointed Organist at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and it was there that his second major composition, a ballet entitled L’Ile Enchantée, was produced in May 1864. Also in 1864, his first concert work for chorus and orchestra, the masque Kenilworth, had its première at the Birmingham Festival. Commissions were beginning to come along, and 1866 saw the first performances of his ’cello concerto and symphony in E (later known as “the Irish”) as well as the overture In Memoriam, the composer’s outpouring of grief at the sudden death of his father. Also in 1866, Sullivan accepted an invitation to write the music for an operatic adaptation by Francis Cowley Burnand (1836–1917) of John Maddison Morton’s (1811– 91) well known farce Box and Cox. Originally intended purely for private presentation, the one-act “triumviretta” Cox and Box was so successful that public performances followed and the collaborators produced a full-scale operetta in two acts, The Contrabandista (1867). In 1869, Sullivan produced his first large-scale sacred work, the hour-long oratorio The Prodigal Son, for the Three Choirs Festival at Worcester. The peace cantata On Shore and Sea (1871) and a massive Festival Te Deum (1872) to commemorate the recovery of the Prince of Wales from typhoid, pointed the way to The Light of the World, a full-length oratorio telling the story of the life of Christ. This was first performed at the Birmingham Festival in 1873. The previous Birmingham Festival (1870) had commissioned the Overture di Ballo. 1871 saw the composition of the best-known of Sullivan’s seventy-odd hymn tunes, “St. Gertrude”, for the Revd. Sabine Baring-Gould’s (1834 –1924) verses beginning “Onward, Christian soldiers”. Sullivan did not forget the stage during this period in his career, providing incidental music for productions of The Merchant of Venice (1871) and The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874) and, also in 1871, collaborating with William Schwenck Gilbert (1836 –1911) on a Christmas novelty, Thespis, for John Hollingshead’s (1827–1904) Gaiety Theatre. This did well enough and, with a run of 63 performances, outlasted most of that season’s Christmas pantomimes. It was good enough to be chosen for a benefit performance in April 1872, but made no major lasting impression.

Sullivan’s next invitation to write for the stage came early in 1875 when Richard D’Oyly Carte (1844 –1901), a rising young impressario, needed a short piece to complete a triple bill at London’s Royalty Theatre. W. S. Gilbert had a libretto ready, but no composer. Carte suggested Sullivan. The libretto was Trial by Jury; Sullivan liked it and the rest, as they say, is history. Trial was an immediate success and Carte, realising the potential of the new partnership, contracted Sullivan and Gilbert to write for him. Their first two-act piece for Carte, The Sorcerer, appeared in 1877 and new operas followed roughly annually until 1889: H.M.S. Pinafore (1878); The Pirates of Penzance (1879); Patience (1881); Iolanthe (1882); Princess Ida (1884); The Mikado (1885 – the greatest success of the partnership and still their most successful joint work); Ruddigore (1887); The Yeomen of the Guard (1888); The Gondoliers (1889). Throughout this period Sullivan continued his work in other fields. In 1880 he was appointed conductor of the Leeds Triennial Musical Festival, which he raised to the highest artistic standards before being deposed after the 1898 Festival by supporters of Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924). For Leeds he wrote his two most famous and successful choral works: the sacred musical drama The Martyr of Antioch (1880; adapted as an opera 1898) and the cantata The Golden Legend (1886). The success of the Legend was so great in Sullivan’s lifetime that it was second in popularity only to Handel’s Messiah and the composer actually took steps to suppress performances to prevent the piece from becoming too hackneyed. He continued his association with Shakespeare, writing incidental music for productions of Henry VIII (1877) and Macbeth (1888). The Macbeth music, for a spectacular production by Henry Irving (1838 –1905) at the Lyceum, consisted of no fewer than fourteen movements, including a substantial concert overture which had a significant independent life. The composer himself arranged a concert suite from Macbeth for the Leeds Festival of 1889. The best-known and most frequently performed of all Sullivan’s compositions, the song “The Lost Chord ”, belongs to this period. Sullivan’s setting of words by Adelaide Anne Procter (1825 – 64) was composed during the throes of his elder brother Frederic’s final illness in January 1877. Having already received honorary doctorates from both Oxford and Cambridge universities, Sullivan was knighted in 1883 for his services to music.

Both Sullivan and Gilbert became wealthy men as a result of their collaborations. D’Oyly Carte became richer than either and built the Savoy Theatre in 1881 to house the pair’s works (Patience transferred there from the Opéra Comique in October), followed by the Savoy Hotel. He then turned his ambition to the foundation of a school of English grand opera and built a new theatre in Cambridge Circus, the Royal English Opera House. Sullivan was invited to compose the inaugural opera and he responded with a setting in three acts of a libretto by Julian Sturgis (1848 –1904) from Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe. Ivanhoe opened in January 1891 and was a great success, running for 155 consecutive performances, an unprecedented number for a serious opera. Unfortunately, Carte had not provided any other British operas for his school and, after running a French piece and briefly reviving Ivanhoe, was forced to lease, and eventually sell, his opera house. It survives as the Palace Theatre. In the meantime, relations between Sullivan, Gilbert and Carte had deteriorated, culminating in Gilbert suing the other two in 1890 as a result of the so-called “carpet quarrel”. In 1892, Sullivan wrote Haddon Hall, an “English Light Opera” dealing with an actual historical event: the sixteenth-century elopement from Haddon, in Derbyshire, of Dorothy Vernon and John Manners. This piece, with a libretto by Sydney Grundy (1848 –1914), had a respectable run. The following year saw Utopia Limited from the reconciled Gilbert and Sullivan. A series of unsuccessful operas then followed: The Chieftain (1894; an extended, reworked version of The Contrabandista); The Grand Duke (1896; his last collaboration with Gilbert) and The Beauty Stone (1898; Arthur Wing Pinero (1855 –1934) and Joseph Comyns Carr (1849 –1916)). All these works suffered from deeply flawed libretti. Then in 1899 Sullivan found a congenial and gifted partner in Basil Hood (1864 –1917) and their first collaboration, The Rose of Persia, was a considerable success with critics and public alike.

Throughout his career Sullivan occupied a place as a kind of unofficial composer laureate and he was frequently called upon to compose music for royal or state occasions. When Queen Victoria celebrated her diamond jubilee in 1897 he received a royal command to set the Jubilee Hymn to music. He also composed a ballet, Victoria and Merrie England, which told the story of Britain’s greatness in a series of tableaux. The ballet was one of the great successes of jubilee year, running for six months at the Alhambra Theatre. His last great popular success was his setting of Rudyard Kipling’s (1865–1936) poem “The Absentminded Beggar ” in November 1899 for the Daily Mail’s fund for the wives and families of those serving in the Boer War. His final completed work was a commission in 1900 from the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s Cathedral for a setting of the Te Deum Laudamus to commemorate the expected British victory in the war. In the summer of 1900 Sullivan was working on a second opera with Hood, but his health, which had never been good, declined rapidly in the autumn and he died on 22 November – the feast day of St. Cecilia, patron saint of music. His own wish to be buried with his beloved parents and brother in Brompton Cemetery was over-ridden by the Queen, who commanded that he be laid to rest in St. Paul’s after what amounted to a state funeral. The Hood opera, The Emerald Isle, was completed by Edward German (1862–1936) and had its première at the Savoy Theatre in April 1901. The Boer War Te Deum duly received its first performance in St. Paul’s Cathedral in June 1902.