Everywhere else I live – well, it doesn’t matter to me, but this house is different, so that sometimes you ask yourself what make all those shadows in an empty room.

Jean Rhys, ‘Let Them Call It Jazz’, Collected Short Stories

Hôtel Cheruseau, Rue Louis en L’Ile, 1905

I came across some of Atget’s photographs at the V&A Museum in London and was instantly drawn to them. These are the staircases, mysterious and intriguing, they are empty spaces that retain an atmosphere, and that say something about presence and absence.

Eugene Atget (1857-1927) photographed Paris for nearly thirty years producing somewhere around 8500 glass negatives and prints, many of which were sold to artists and individuals. He had a studio on the same street in Montparnasse as Man Ray, with a sign over his door ‘Documents for Artists’. Only four of his images were published during his lifetime in La Revolution Surrealiste, and he insisted on remaining uncredited for this work. Man Ray’s assistant, Berenice Abbott was a key figure in collecting and cataloguing his work, and in publishing a book with a number of his photographs. There is a large collection of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

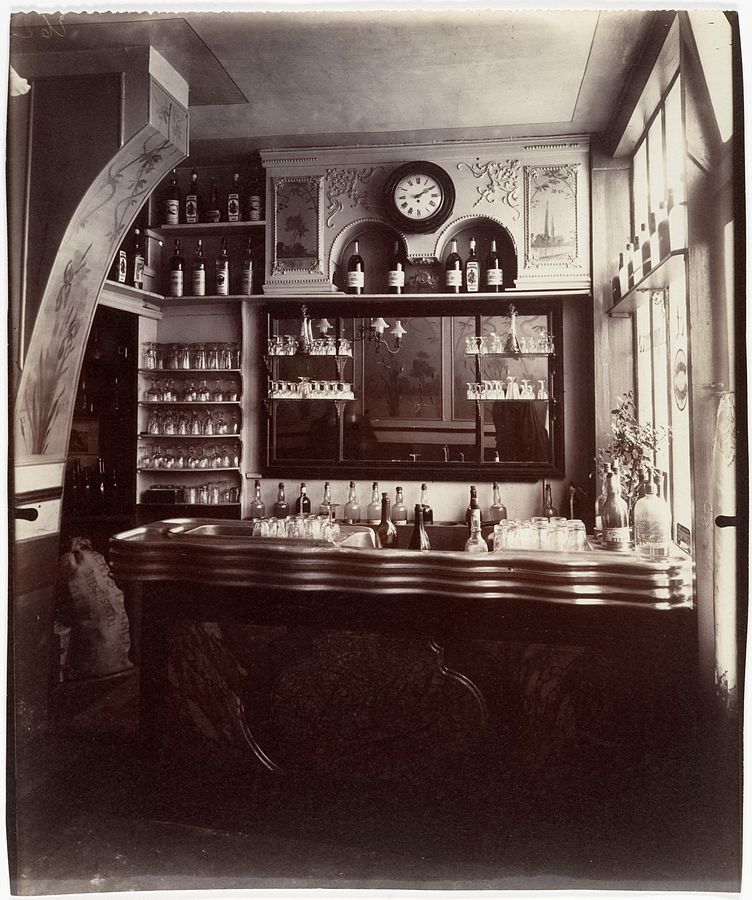

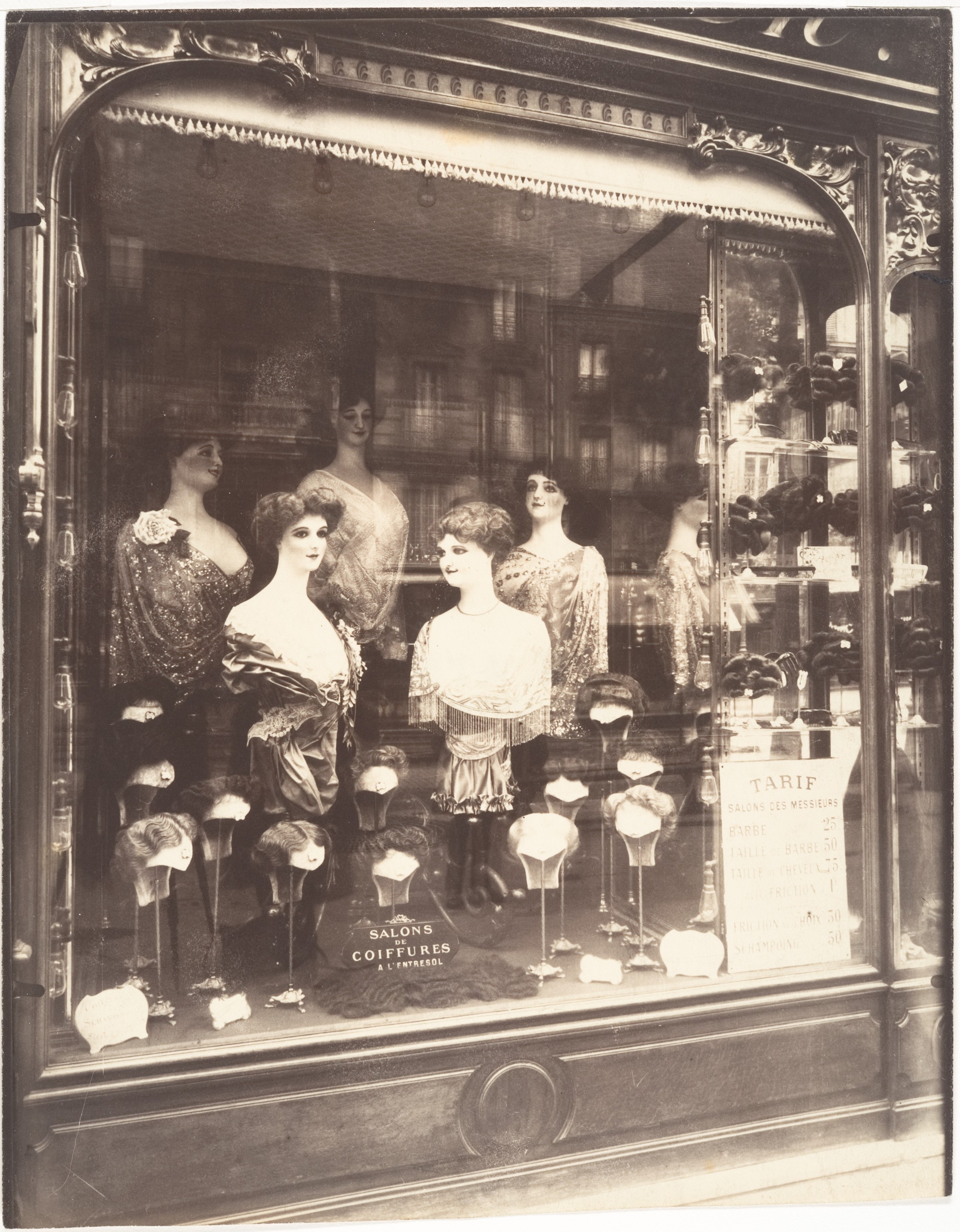

Atget’s project to photograph a disappearing Paris, places him in the tradition of street photography and the flâneur, observing the city, preserving and capturing its details and subjects. His photographs capture a moment contained within the spaces of a Paris in flux. They capture the transitory, fleeting glimpses of courtyards, streets, shop windows, interiors and reflections. Walter Benjamin referred to them as like ‘the scene of a crime’; perhaps in their status as documents of a disappearing city they can be seen as evidence, open to interpretation. They ‘thematize the spatially and temporally liminal that is the focus of Benjamin’s reading of Surrealism’ (Dana MacFarlane).

Benjamin made Atget a key figure in his discussion of the surrealist aesthetic. The political force of surrealism lies in its simultaneous intensification and overcoming of conceptual, spatial and temporal boundaries.

Dana MacFarlane (2010) Photography at the Threshold: Atget, Benjamin and Surrealism, History of Photography, 34:1, 17-28, DOI: 10.1080/03087290903361365

The emptiness of their spaces suggests a region outside the everyday, in which doors, stairways and passages appear not as the backdrop but as the subject of his photographs. They reverse the relation between prominent subject and background, as shown in this image of the Panthéon.

Glimpses inside and though buildings – the interpretation of spatial configurations – took increasing command of his interest. And with this he was quick to come up with new compositional formulae that flew in the face of convention. Strong contrasts, hard shadows that created an impression of depth and intersecting forms became the hallmark of his photographic vision. Open gates and doorways reveal objects left by chance, which invite the viewer to imagine the hidden reality behind the pictures and to read the objects as clues to some story about ordinary life.

Andreas Krase, ‘Introduction’, Atget, Taschen Icons

Like Jean Rhys, Atget has an aesthetic interest in shadows and in border regions and peripheries. His photographs include itinerant workers, street traders and musicians; those existing on the social and economic margins.

Eugène Atget, Street Musicians, 1898-99

Eugène Atget, Joueur de Guitare, 1900

Spaces are turned inside out, so that streets and exteriors often appear enclosed, and his photographs ‘demonstrate an ambiguous reality in which inside and outside seem to merge, and ghostly faces loom into sight and mingle with the reflections of the surrounding buildings’ (Andreas Krase). This is suggestive of Benjamin’s flâneur : ‘the city neatly splits for him into its dialectical poles: it opens up to him as a landscape, even as it closes around him as a room.’

The photographs that move me are the interiors, the empty spaces and staircases of hotels. The sense of neglect, abandonment and emptiness. A faded grandeur and elegance, cataloging the decorated ironwork and ornate railings, they are a testament to something that is fading out of view. Their very emptiness, their absence, is suggestive of presence, in the sense of what might be found around the corner, just out of view, or who might come through the door. There seems an instinct to preserve and record the existence of these spaces even as they are beginning to fade from view and disappear.

Atget’s shop windows display mannequins and objects that appear somewhere between the real and inanimate, and reflections of the street outside appear in the windows.

Eugène Atget, Marchand de Vin, Rue Boyer, Paris, 1910-11

Eugène Atget, Coiffure, Boulevard de Strasbourg, 1912

Watching Agnes Varda’s film, Daguerrotypes, I am entranced by her portrayal of the shopkeepers in the Rue Daguerre, the film is like a lost age preserved and captured; a reminder that we are unable to see time as it changes before our eyes.

Atget remains an enigmatic figure and Andreas Krase remarks that he appears intentionally to have covered his tracks, leaving his photographs open to interpretation. In some of his pictures appears the shadowy outline of the photographer caught in his own images, reflected on the glass panes of doors and windows, in this way leaving ‘a trace of his presence: in the reflective surface of a fire-screen we see a darkly shrouded being with a lens, like the symbol of a photographer … a game with reflections’.

I realize I am becoming involved, intrigued, consumed by passages and interiors. The glimpse into a courtyard, the stillness of life, the passing by of an interior from the street. The secret hidden life of the city. What self-portrait do I, the author, the detective, the shadow leave here?

They are not lonely, merely without mood; the city in these pictures looks cleared out, like a lodging that has not yet found a new tenant. It is in these achievements that Surrealist photography sets the scene for a salutary estrangement between man and his surroundings. It gives free play to the politically educated eye, under whose gaze all intimacies are sacrificed to the illumination of detail.

Dana MacFarlane (2010) Photography at the Threshold: Atget, Benjamin and Surrealism, History of Photography, 34:1, 17-28, DOI: 10.1080/03087290903361365