In the midcentury Popular Science future, the 21st century boasted flying cars and jetpacks and tall buildings with ramps spiraling around them. The sky was always blue, the people always happy and white. 2000 A.D. would find us all in a technological paradise. But by the closing decades of the century, that vision had changed to something more nuanced and complex, even sinister. In 1982 I saw a new film by Ridley Scott called Blade Runner. I watched it in Los Angeles with my friend David Scharf (whose electron microscope photograph—actually of pot buds—appears in the sushi bar scene). Afterward we agreed the future would never be the same. We can thank Syd Mead, the film’s “visual futurist,” for that.

Sydney Jay Mead, who was born in 1933, is often credited with perfect vision for the future. He died on Dec. 30, just barely missing 2020. A graduate of the Art Center School in L.A., he started his career as an industrial designer at Ford. He soon formed his own industrial design company. But he’s best remembered for work he began in his 40s: creating the futurescapes of Blade Runner (set in 2019), Tron, Aliens, and more.

Blade Runner did to the “old” future what Kubrick’s gleaming spaceships in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) did to tacky Flash Gordon–era spaceships. In Blade Runner, Syd imagined the look of an all-too-plausible grimy and dystopian future. The film marked a dramatic shift in our expectations of the coming centuries. The Disneyesque Tomorrowland of world’s fairs collapsed into a more apprehensive sense of the comeuppance of centuries of human mischief, with a less friendly view of aliens, robots, computers, and corporations.

But the grittiness of Blade Runner is misleading. Syd’s spouse, Roger Servick, told the New York Times that the design of Blade Runner

was an interpretation of someone else’s vision, not Mr. Mead’s own.

“He always tried to make sure that people knew that was not his idea of the future, that was Philip K. Dick’s idea of the future,” he said.

Mr. Mead’s view was considerably more optimistic. “What we need to do,” Mr. Servick said, summarizing it, “is work toward a better future, spend our efforts trying to make things better.”

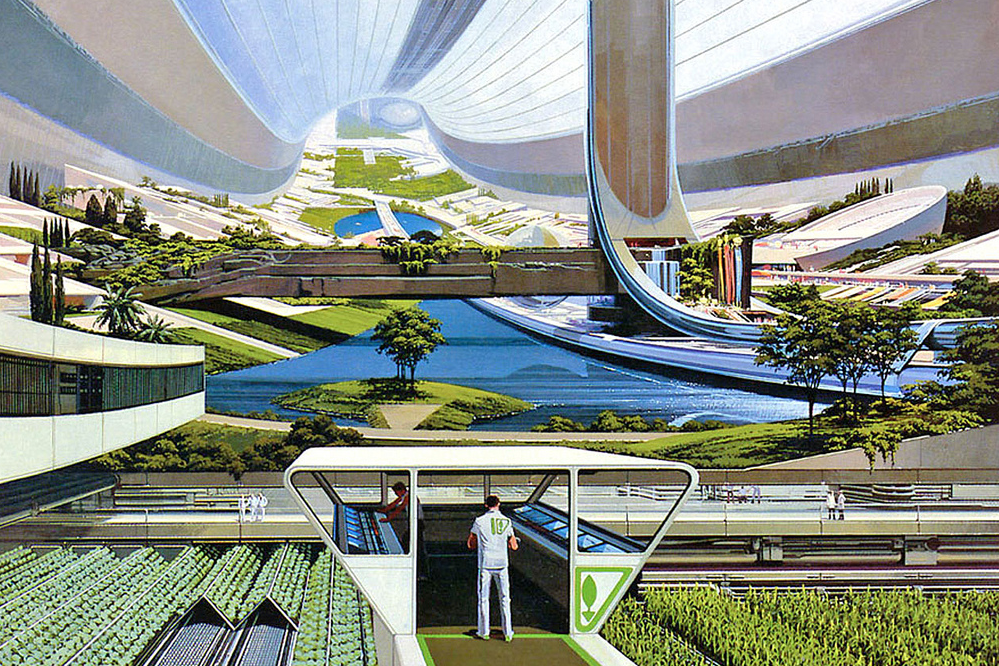

Syd’s work often celebrated technology with no reservations about costs or consequences. You’d love to drive his sleek vehicles, which always looked straight out of the car wash, or work in his billion-dollar megabuildings. His cities are so powerfully streamlined that one almost expects them to launch into orbit, or at least go from zero to 60 in 7 seconds flat.

Yet Syd’s future has no blade of wild grass, not even pigeons. In this techno-future, nature is not so much tamed as ignored. Perhaps tellingly, this is why even his optimistic techno-marvels often seem hard, even cold. In Syd’s future, humans seem happy to be alone with their machines. In Tron (1982), for instance, nature is dispensed with entirely for a world of pure industrial design.

In photos Syd looks nothing like a visionary artist. In his younger days you might have pegged him as a NASA engineer, with his white shirt and skinny black tie. As he aged, he looked more like an Indy 500 car driver. In some ways he was deeply conservative. Rather than dream in his own private space, he was engaged in the real world as a highly successful industrial designer. In fact, some of his designs actually were used in the design of cars in the San Francisco BART system. He also drew many architectural renderings for nonfuturistic city plans with innovative roadways and other features. In his more imaginative work, he drew from sources as varied as automotive designs and the “arcologies” of the visionary architect Paolo Soleri.

Any artist would admire Syd’s mastery of technical skills, his absolute command of perspective and the way light falls on variably curved surfaces. His reflective surfaces have a heft and reality—not to mention beauty—the rest of us could only envy and try to match. His influence can be seen in many subsequent science fiction spacecraft (which don’t really need all that cool streamlining in interstellar space).

That’s because, ironically, Syd was old-school, one of the last great artists of the old 20th-century style of professional illustration. Trained in classical art techniques before perfecting his skills as a high-priced designer in the auto industry, Syd mastered tools now obsolete. He was of a generation of traditional art students whose final exam in perspective drawing would be to draw a room with a mirror leaning at an angle against a wall. Students were graded on how accurately they could draw the reflection in the mirror.

Rendering such perfect perspective without a computer is a skill now as rare as extracting square and cube roots manually. But Syd could do it because he was a product of that bygone era of drafting tables cluttered with T-squares and French curves and technical drawing pens, as nostalgia-inducing now to us remaining old 20th-century hands as slide rules and buggy whips. Nobody still working can draw like that anymore. Today Syd’s renderings would all be done on a computer, and therefore lack the vitality he breathed into every line.

How did his colleagues regard him? We feared him. I was chief artist on Carl Sagan’s original Cosmos series, which was in production in 1979, at the same time as Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Syd’s first movie gig. I already knew his work and was intimidated when I learned he was designing for that film, whose special effects budget far exceeded ours. We were struggling with how to depict Carl’s “Spaceship of the Imagination,” which would inevitably be compared to spacecraft in big hit films. After seeing a few Mead production images, I threw in the towel and opted for a more symbolic approach to spaceship design—hence the dandelion spaceship motif. I certainly wasn’t going head-to-head with Syd Mead in designing cool-looking spaceships.

R.I.P., Syd.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.