When I was a teenager, back in the 1980s and early 1990s, there was no multi-channel TV (not in our house anyway), and so on a wet afternoon during a school holiday, the only TV available was likely to be an afternoon film on Channel 4 or BBC2. It was then that I first saw Victim (1961). It was being shown as part of a short season of Dirk Bogarde films on Channel 4 – alongside Libel (1960), I believe, and probably I Could Go on Singing (1963). It was shown a few weeks after The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), and it was remarkable to me to see two films in quick succession where the lead characters were gay.

Both films had a huge effect on me at the time – although I couldn’t tell anyone about that, of course – and the effect Victim had on gay men in the early 1960s has been well documented. Just think of what a gamechanger the title of the film was, let alone the content of the movie. Here was a gay man, guilty in the eyes of the law, being referred to as the victim of it. The film consequently helped forward the discussions around the issue, and homosexuality was decriminalised just a few years later. If it were only for that one film, the 100th anniversary of Dirk Bogarde’s birth this week would be a cause for celebration and appreciation. Here, after all, was a man who put his career on the line in order to play that lead role.

There were many over the years that grew frustrated with Bogarde’s unwillingness to talk about his own sexuality, and “come out” of the closet. Indeed, one could wonder why a man who was willing to play a role like that in Victim didn’t actually talk openly in his later years about the fact he was himself gay. Perhaps, by that point, it had become almost a game to dodge the question and see his interviewers get frustrated.

When a smug Russell Harty tried to probe him on the subject in 1986 during a TV interview, and clearly thought he was about to get a public admission for the first time, Bogarde said with great self-satisfaction: “I’m still in the shell, and you haven’t cracked it yet, honey!” As it is, he did at least quietly admit his relationship with Tony Forwood in an interview with Barry Norman a few years later, referring to him as his “partner.” Ironically, Harty was looking to make headlines by getting such an admission on tape, whereas on the Barry Norman interview it just slips out in quiet, polite conversation.

Dirk Bogarde was, or at least appeared to be, something of a contradiction. Many refer to him as a recluse, or an intensely private person. And there is still the notion that he was and is more appreciated in mainland Europe than in the UK. And yet there were numerous interviews with him in the 1980s in particular on UK television, including an episode of Parkinson, in which he sat in the hotseat alongside Barbara Woodhouse – what I wouldn’t give to see that! There were also appearances on chat shows hosted by Michael Aspel and Russell Harty, as well as the Film 90 appearance mentioned earlier. There was also an Omnibus episode dedicated to him for which he was interviewed, and a two-hour interview entitled By Myself, made for Channel 4 in 1992. These programmes would suggest that he was neither reclusive or under-appreciated in the UK during his lifetime. And it’s not as if he moves away from difficult subjects during them. He talks movingly, for instance, about how he was there at the liberation of Belsen Concentration Camp, for example.

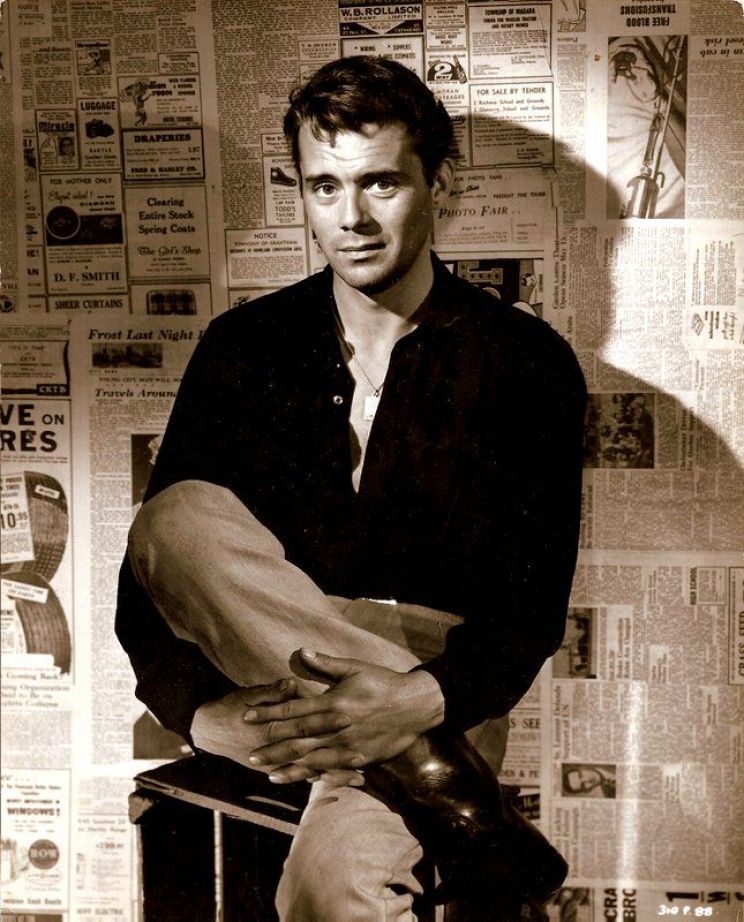

While Victim will always be the most talked-about Bogarde film, there are so many others that deserve mention. Even during his years in the 1950s as a matinee idol for the Rank studio, for every Doctor in the House there was another film which was slightly left-field or which pushed him as an actor: The Gentle Gunman (1952), The Sleeping Tiger (1954), The Spanish Gardener (1955), The Doctor’s Dilemma (1958), Libel (1959) and the infamous The Singer Not the Song (1961), in which he spent most of the film in tight leather trousers that didn’t leave much to the imagination.

His career path after the early 1960s certainly wouldn’t have appealed to everyone, as he set about finding more and more interesting “difficult” roles in the wake of Victim. There were still commercial movies such as Doctor in Distress (1963) and the under-rated Hot Enough for June (1964), but he also made a string of films with Joseph Losey, with whom he had first worked during The Sleeping Tiger. The Servant (1963), King and Country (1964) and Accident (1967) were all superb, dark dramas directed by Losey, in which Bogarde moved further and further away from his earlier image of a matinee idol – and that’s without mentioning Darling (1965) and The Damned (1969). The Damned was his first movie directed by Visconti, and it was followed by Death in Venice (1971). I would have said “swiftly followed,” but nothing moves swiftly in a Visconti movie.

Death in Venice and most of the films that followed over the next twenty years were made while Bogarde lived in France. They are mostly arthouse films, and that was clearly intentional. He clearly was only interested by this point in making movies that he wanted to make, and on his own terms. They are not for everyone. For every person who thinks Death in Venice is a masterwork, another will think it pretentious, difficult, or even just dull. Perhaps it is all four of those. In 1978, he was in Despair, a film directed by Fassbinder. Bogarde believed the film to be great, but that Fassbinder completely ruined it by continually editing it, and he was dismayed when he finally saw the movie. He didn’t make another film for the cinema until 1990.

In the 1970s, there was still the occasional mainstream movie, such as the war drama A Bridge Too Far (or, as I prefer to call it, An Hour Too Long). Bogarde then made three TV dramas in the 1980s, including The Vision, made for BBC2, in which he stars alongside Lee Remick as a has-been TV personality offered a job by a new channel run by a religious group which might have sinister intentions. It has its flaws, but it still is well worth hunting down.

When Bogarde semi-retired from acting in the 1970s, he started producing a string of novels and autobiographies that gained critical acclaim. It is debatable just how much the autobiographies are actually truthful about his private life, but few have skirted the truth with such intelligence and eloquence. One of them, Snakes and Ladders, includes as an appendix the climactic scene for I Could Go on Singing that Bogarde had re-written after he and co-star Judy Garland were somewhat dismayed at the original version. That ten-minute scene, filmed in one long take, makes the whole film worthwhile and the two stars gave a masterclass in acting – even as seen in the appalling quality of the YouTube video.

Today, Bogarde perhaps suffers from the same issue that so many other great artists have suffered – his work cannot be put into a single box and neatly labelled. There probably isn’t another British actor whose work had covered so many bases as Bogarde’s, from a film such as Doctor in the House – a mainstream, audience pleasing, romantic comedy – through to a film like Providence (1977), which those same mainstream audiences are likely to find impenetrable.

Dirk Bogarde was, and is, a national treasure, whose work is not only remarkable, intelligent and challenging, but which also helped to change the lives of many of those who saw it.

Happy birthday, Dirk.

I just watch a 2001 Documentary The Private Dirk Bogarde and he certainly is a contradictory character,I have been discovering his work over the past 2 years,thanks for the nice tribute.