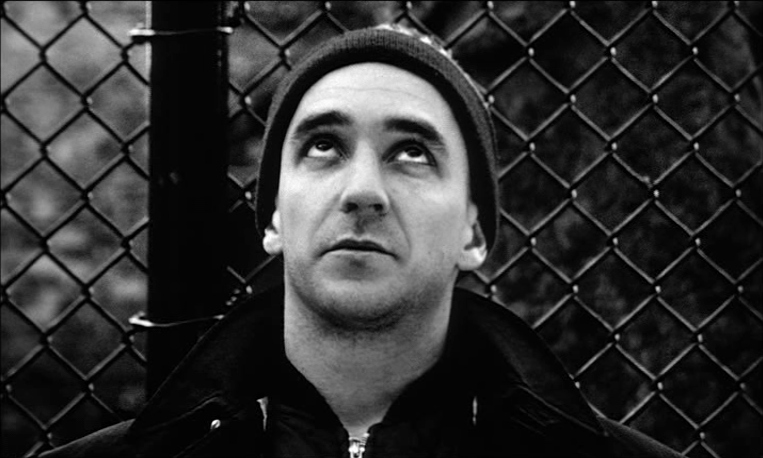

Darren Aronofsky | 1hr 24min

The singular, unifying code which connects all aspects of the universe in Pi cannot be solely attained through the calculations of greedy businessmen, nor divined through religious texts. It transcends humanity and even God himself, laying out the basic foundations of existence and explaining everything there is to know. Wall Street brokers and theologians alike chase it down, believing it can predict the stock market and reveal the true name of Yahweh, and yet the prophet who has been bestowed with this knowledge is reluctant to let fall into the hands of any ideological faction. When it comes to mathematics, Max Cohen is a purist, believing that his 216-digit number is simultaneously a gift from a perfectly logical universe, and a weapon far too easily exploited by self-serving humans.

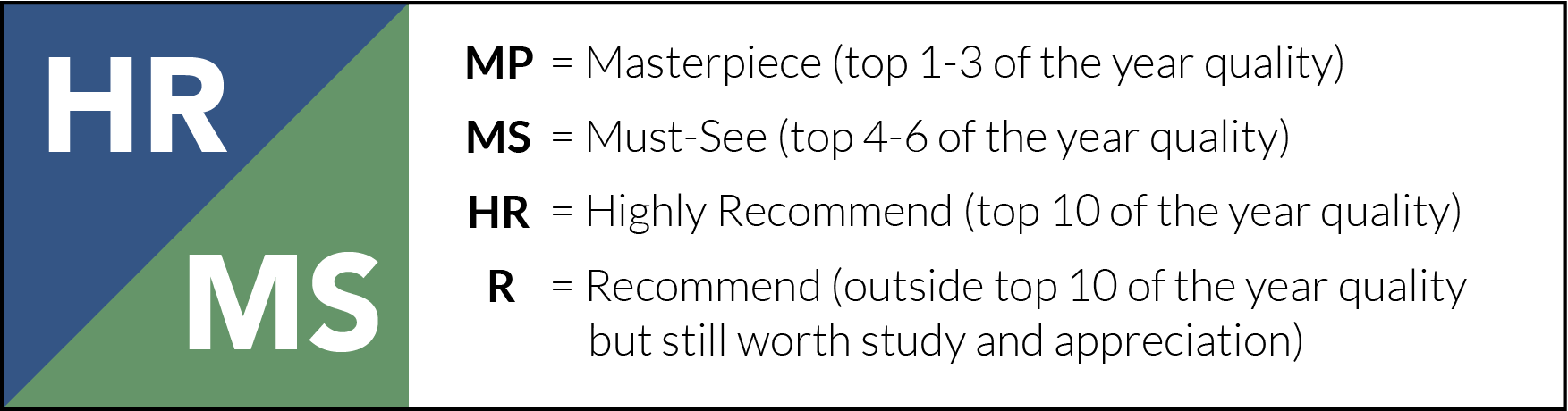

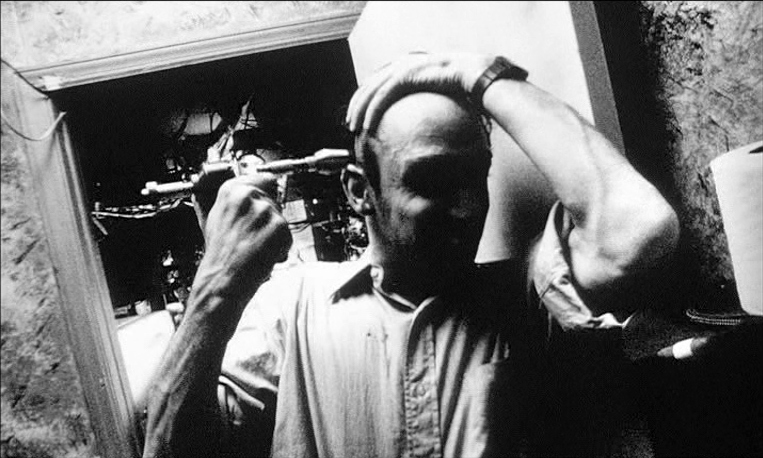

Right from the first close-up of his face squashed against his computer desk, Darren Aronofsky inhabits the mind of this reclusive number theorist with painstaking discomfort, making a debut as equally haunted by sensory and mental disturbances as his own tormented subject. Part of this has to do with the grainy monochrome aesthetic he crafts, driving a harsh distinction between the blacks and whites of each image with an enormously high contrast, and cluttering his mise-en-scène with monitors, lights, and cables running all over the set. Given how hideous this is to look at much of the time though, it would be hard to call this an unadulterated visual triumph.

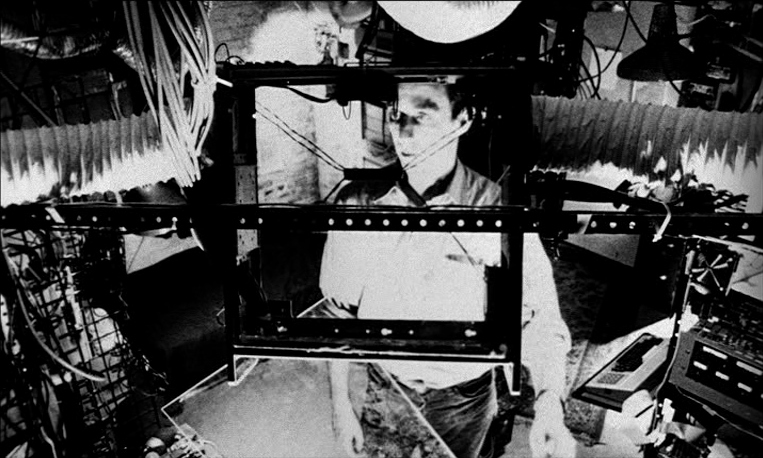

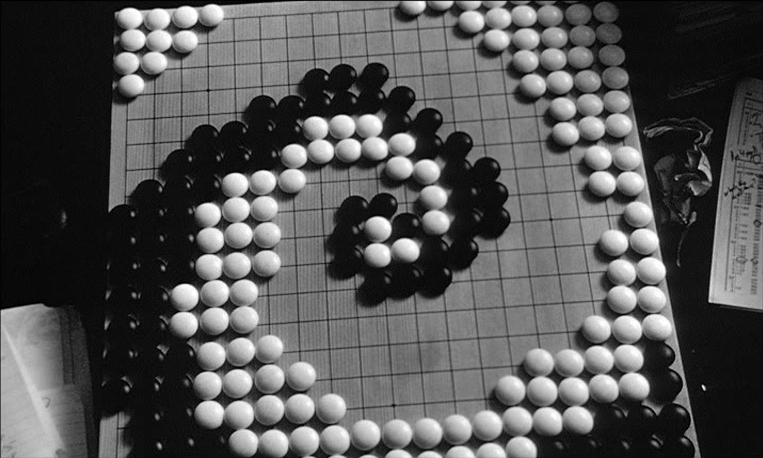

It is rather in Pi’s pulsating, formal rhythms that Aronofsky unites his creative tools behind a wholly disorientating vision, manifesting the aggressive concoction of illnesses plaguing Max’s mind and body. Central to this is his vigorous editing, cutting fast through visual demonstrations of the mathematician’s hyperactive, stream-of-consciousness voiceover that can’t stop spilling out abstract theories. The emergence of the Fibonacci sequence in game theory, the stock market, and biological evolution supports his primary belief that patterns can be found in every facet of life and beyond, forming an objective foundation of existence that transcends the whims of humanity. Driven to equally establish order from his muddled thoughts, Max methodically lists off his assumptions in a list.

“One, mathematics is the language of nature. Two, everything around us can be represented and understood through numbers. Three, if you graph the numbers of any system, patterns emerge. Therefore, there are patterns everywhere in nature.”

Perhaps this rational stability is why he is so drawn to maths in the first place, given his own acute psychological suffering. His headaches, anxiety, and schizophrenic hallucinations frequently manifest in extreme close-ups and rapid jump cuts, and sharp mini-montages also flash through his quick downing of pills to quell these symptoms. Through a highly-strung electronic score and amplified sound design, Pi sensitises us even further to the sound and movement of its relentless, propulsive thrum, juxtaposing Max’s frenzied obsession against the cold rationality of the universe.

These editing and aural devices would later be refined in Requiem for a Dream, with Aronofsky even bringing composer Clint Mansell back to score its haunting them ‘Lux Aeterna’, but the surrealism he dabbles in here is far more detached from any reality present in that mind-bending trip. This is a character study of intensive, psychedelic focus, desperately scrabbling to make sense out of an all-encompassing chaos, yet often falling to Max’s horrific delusions. In one scene he halts as he makes his way through a subway station, coming across something that lies just behind the camera, and in the reverse shot we see his brain. As if trying to penetrate its mysteries, he pokes it with a pen, and yet each time we cut back to him flinching in shock and pain. As Aronofsky disintegrates the laws of physical space and enters an entirely unfamiliar psychological realm, reality ceases to exist, and all we are left with is the obsessive mania of this neurotic genius.

By the time the conspiracy surrounding his cryptic 216-digit number has fully emerged, there is no holding Max back from descending right to the depths of paranoia. Lenny, a Hasidic Jew with a keen interest in number theory, is determined to take him back to his sect which believes the code will bring about the Messianic Age. Marcy Dawson, a Wall Street agent, is just as dogged in her efforts to claim the number, convinced that it is the key to manipulating the stock market. The number is relevant to every corner of society, yet only Max sees its value beyond its utility, as well as the dangerous potential for its exploitation. In this constructed narrative, he is the saviour of a world verging on apocalypse, tasked with protecting secrets no human should ever be allowed to know.

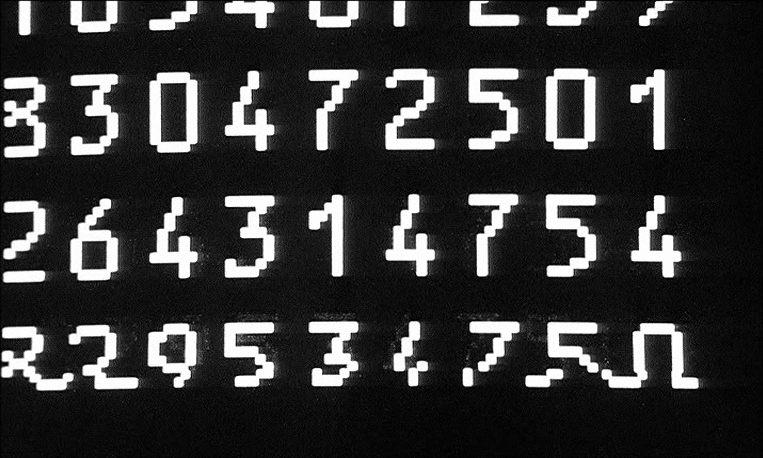

That is, if we can take everything that he perceives at face value. Like the computer that gains consciousness the second it calculates that divine number, becomes aware of its own nature, and immediately melts down, Max is set on a parallel trajectory that erodes his mind the closer he gets to what he believes is enlightenment. Aronofsky underscores the dangers of that hubris in the formal repetition of one specific anecdote throughout the film, as Max reminisces a childhood memory of being cautioned against looking directly at the sun, disobeying the warning, and being temporarily blinded for some time after. Like Icarus from Ancient Greek mythology, his arrogant ambition was his downfall, and continues to ruin him now in his effort to transcend human knowledge.

This number has not brought Max peace in attaining greater wisdom, but rather the opposite, intensifying his headaches and even swelling a bulge on the side of his head. The David Cronenberg influence on Aronofsky is apparent, drawing a close link between bodily mutations and mental degradations, and so for Max it is only with the violent removal of the former that order can be restored to the latter.

It is worth questioning how much of a genius Max truly is versus how much is delusion, especially as Aronofsky laces in plenty of hints that his self-perceived intelligence is purely contrived. Regardless of whether it was self-inflicted brain damage that saved him or a humble acceptance of his own limitations though, Pi draws a surprisingly optimism from its feverish neurosis, with Max discovering an even deeper peace than he ever knew while in the throes of analytical obsession. Within Aronofsky’s acute formal interrogation of intellectual delusion, true order is found not by trying to penetrate a complicated yet rational universe, but rather by accepting its dazzling, wondrous incomprehensibility.

Pi is currently available to rent or buy on Amazon Video.

One thought on “Pi (1998)”