The video coin-op game Elizabeth Falconer managed to get playtested in Spanky’s Saloon, a bar in San Diego, California in 1981 was a far cry from the popular fast-paced space shooters of the day. Falconer, a market researcher at Sega/Gremlin, was tasked to review the company’s library of video presentations to see if anything was worth licensing, here she came across Frogger, a single-player arcade game developed by Japanese Konami. The cute jumping frog was introduced in Japan in January of 1981 before entering mass production in June. Over the following months, Frogger became a huge success and ended up as the 12th highest-grossing arcade game in Japan that year. Sega gained exclusive manufacturing rights to the game worldwide and a demo was sent to Sega/Gremlin in San Diego but the company was somewhat skeptical of its earning potential in North America.

Three years earlier, in 1978, Sega/Gremlin, then Gremlin Industries, had released Frogs, a single-player arcade game featuring a leaping frog. The game had flopped and management was now, understandably, hesitant to bet on yet another frog. Still, Falconer was adamant that Frogger deserved a chance and requested a licensing window for playtesting, reminding management of how the cute little Pac-Man had filled a huge void in the market, appealing to more than just the trigger-happy young male demography, and had become the highest-grossing arcade game in the US in 1981 with more than $1 billion in revenue. Sega/Gremlin agreed to pay Konami $3.500 per day for a 60-day licensing window and a Frogger prototype cabinet was installed in the San Diego bar to test the market. While management believed installing the game in a bar would ruin the playtest because of the male-dominated audience who surely weren’t into cute kid’s games, they were quickly proved wrong. Frogger showed to be immensely successful and based on that single test alone distributors soon agreed to resell the game.

Contemporary reviews praised Frogger as one of the greatest video games of its time and cabinet sales went through the roof earning almost half a billion dollars, in today’s money, becoming one of the top-grossing arcade games in North America in 1981. Like Pac-Man, the basic gameplay and cute presentation led it to be one of the most memorable and influential arcade games ever made. Rights to video consoles and home computer versions were sold off to American toy and game manufacturer Parker Brothers.

Spending millions on advertising, Parker Brothers’ version of Frogger for the Atari 2600 among other systems sold well over 4 million copies in 1982 alone, making it one of the most popular games at the time. Sierra On-Line, then On-Line Systems managed to gain magnetic media rights after discovering that Parker Brothers’ deal with Sega/Gremlin only covered ROM cartridges and not disk and cassette versions of the game. For On-Line Systems just coming off a copyright infringement lawsuit, finally having a license to officially port one of the most successful games of the time, was a huge deal. The drive behind it was programmer prodigy John Harris, whose earlier game Jawbreaker had caused the copyright infringement lawsuit in the first place.

Harris, one of the most influential young developers, had joined Ken and Roberta Williams’ On-Line Systems back in 1981. His games had not only earned him a six-figure income from royalties, and On-Line Systems even more but also a copyright infringement lawsuit courtesy of corporate conglomerate Atari, Inc. The David vs. Goliath case was settled with On-Line Systems surprisingly coming out on top.

Jawbreaker, despite the lawsuit, proved a major success. Praised for its fast-paced gameplay, graphics, music, and sounds, it received critical acclaim and became the Best Computer Action Game in 1982. In 1983, readers of Softline Magazine listed it second on its Top 30 list of popular Atari 8-bit programs, trailing only Star Raiders.

Following Jawbreaker, Harris went on the create the much lesser successful Mouskattack. While carrying elements from the likes of Pac-Man, it was still unique and came with some great added gameplay features but a good game was nothing without convincing sales, and Parker Brothers’ Frogger had exactly that, with millions of sold cartridges.

While the lawsuit came out in favor of On-Line Systems, capitalizing on other people’s property surely wasn’t the right way to go about doing business and Ken Williams became increasingly aware of that. Instead of copying and later dealing with the punches, licensing was the way forward and it wouldn’t be long before he managed to acquire Frogger, the company’s first licensing deal.

Harris, Williams’ star programmer, had been playing Frogger and absolutely loved it. In his mind, the game was a perfect fit and had all the right challenges for becoming a superb game for the capable Atari 8-bit line of home computers, he just needed Williams’ acceptance. The idea of a best-selling coin-op game becoming a best-selling computer game with Williams’ company name on it didn’t require much persuasion and Williams got in contact with the Sega division and managed to acquire the floppy disk and cassette rights for a paltry 10 percent royalty fee.

Harris was immediately put to work on the Atari 400/800 version while Williams assigned another programmer, Olaf Lubeck, to the Apple II version. While the Apple II had been the company’s bread and butter, the system, now five years old was definitely showing its age, the Atari version had to be the priority, showcasing the excellence of Williams company.

Harris, having a vast library of self-developed tools and utilities, estimated the assignment to be a quick three-week project but like most other young programmers he was over-optimistic. He was a perfectionist and wanted his work to be admired for its brilliance of concept and execution, not as much by the consumers but more by his peers. But times were changing as the consumer market rapidly evolved. The days of amateur programmers writing software on their own terms were coming to an end.

Two months in, Harris was near the finish line and took a few days off to go to San Diego for the Software Expo where he would display his creations, including his masterpiece, the nearly completed Frogger. Harris left Oakhurst for Southern California with nearly every piece of software he had ever created, including tools, utilities, graphics, source codes, and games. A few days later he returned to Oakhurst empty-handed. Everything he had done in his young but prolific career had been stolen from right under his nose, including his most important creation to date, Frogger. A conversation and a few moments of distraction at the Expo proved disastrous.

Depressed and upset, the next few months only resulted in a few dozen lines of rewritten code, Harris’ motivation was gone. There was no sympathy from Williams, who was starting to grow tired of babysitting his crowd of rowdy young programmers, people he was paying thousands of dollars to in royalties. Frogger should have been completed within a month and while Harris was contracted by Williams without any agreement on delivery, the delay led to serious complications between the two.

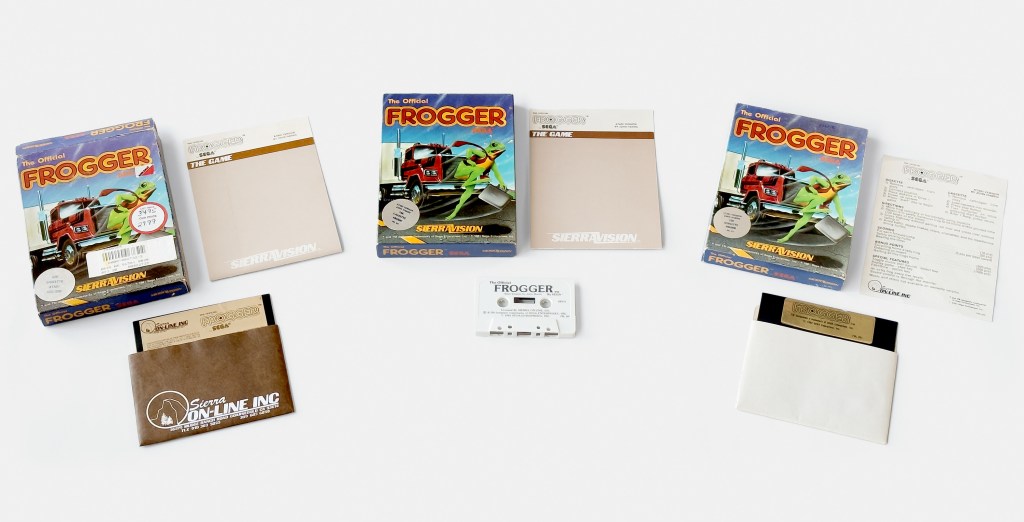

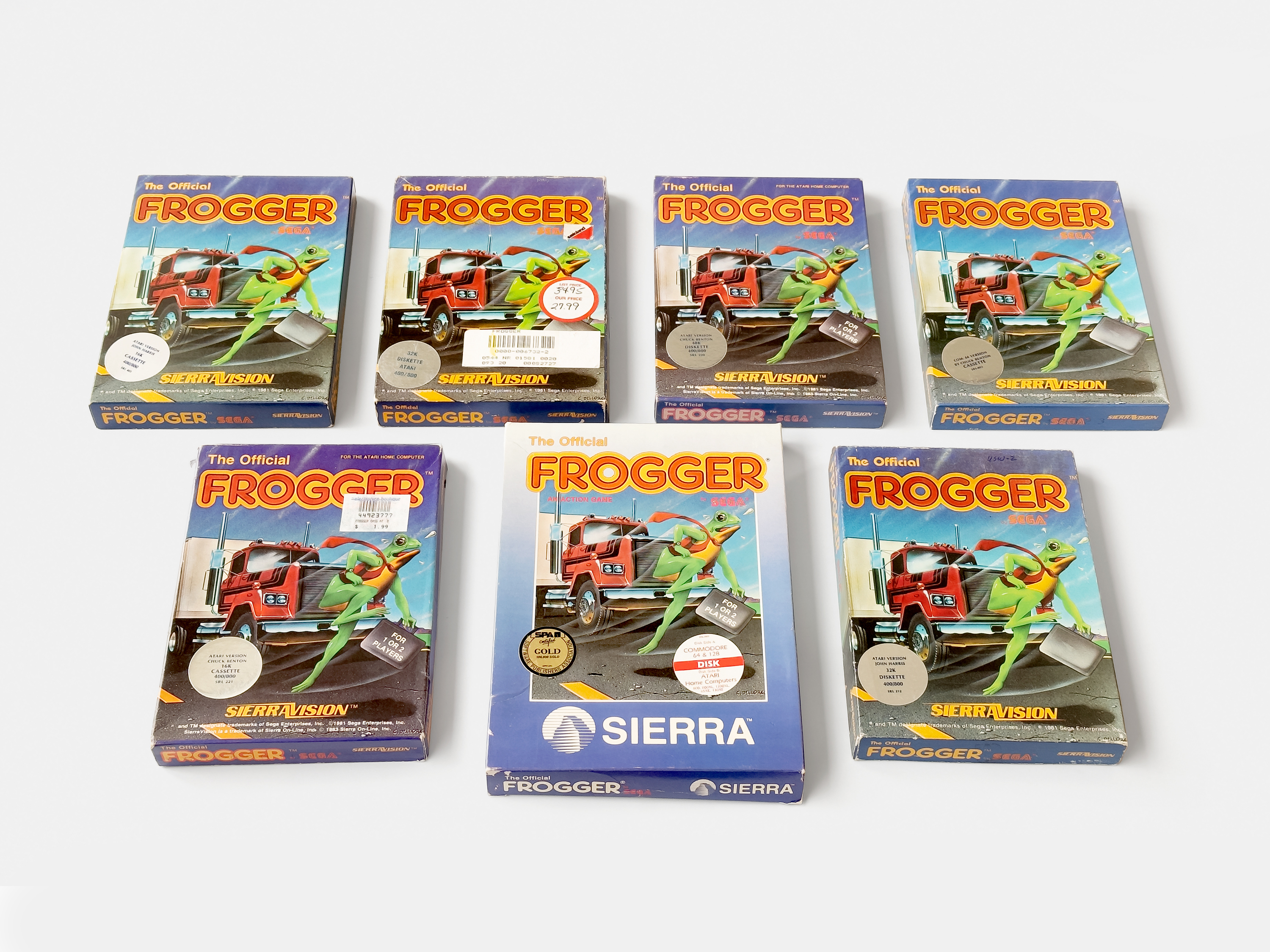

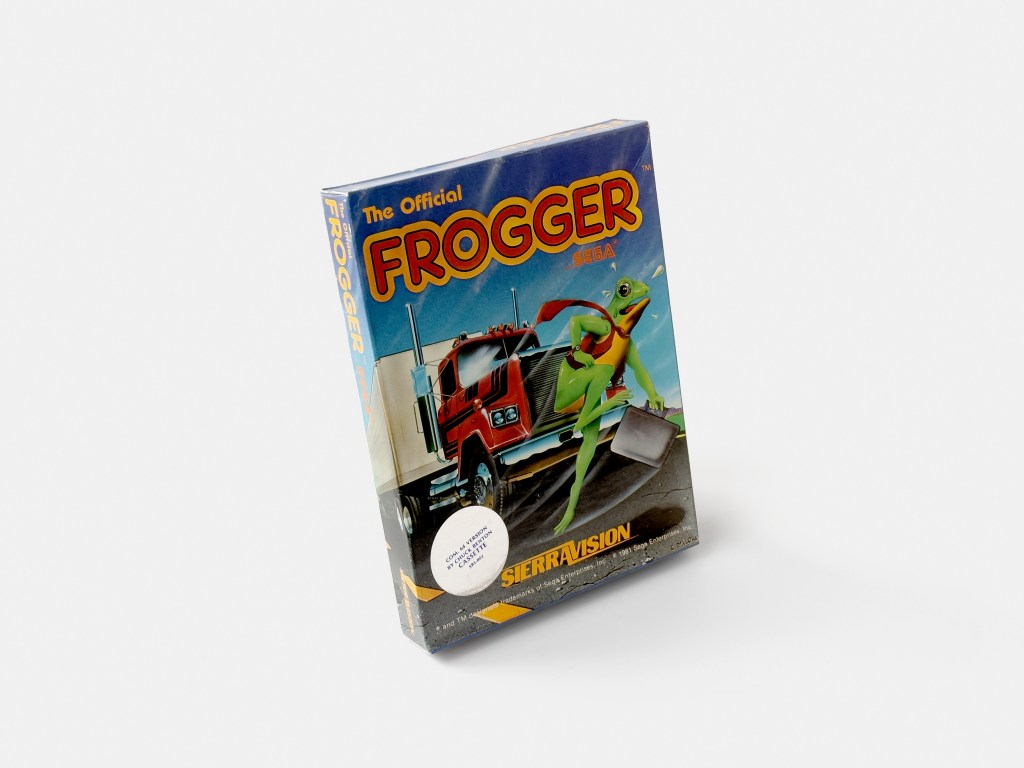

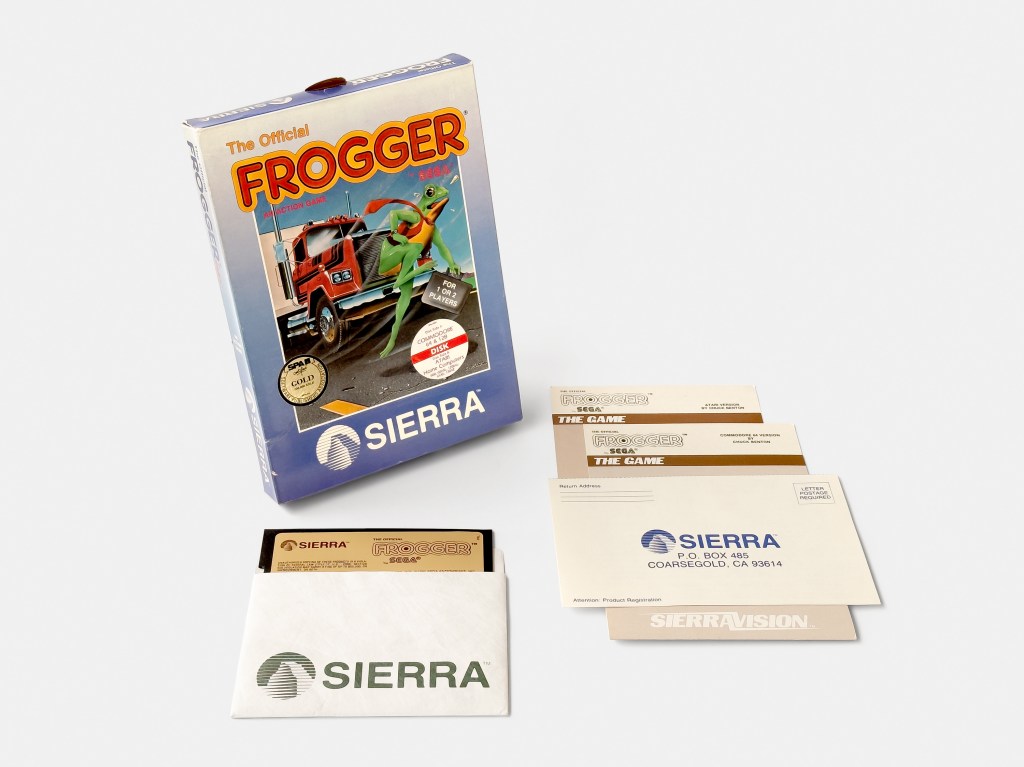

When Harris finally had rewritten Frogger, now with even more bells and whistles it would take another two months before the game finally could be released, the days of non-bureaucracy and quick publishing were over. When Frogger hit the market in late 1982, On-Line Systems was no longer a summer hacker camp but a serious company with investment money and important people to satisfy. The company was now Sierra On-Line and a new label, SierraVision, for the company’s action and cartridge-based games was created.

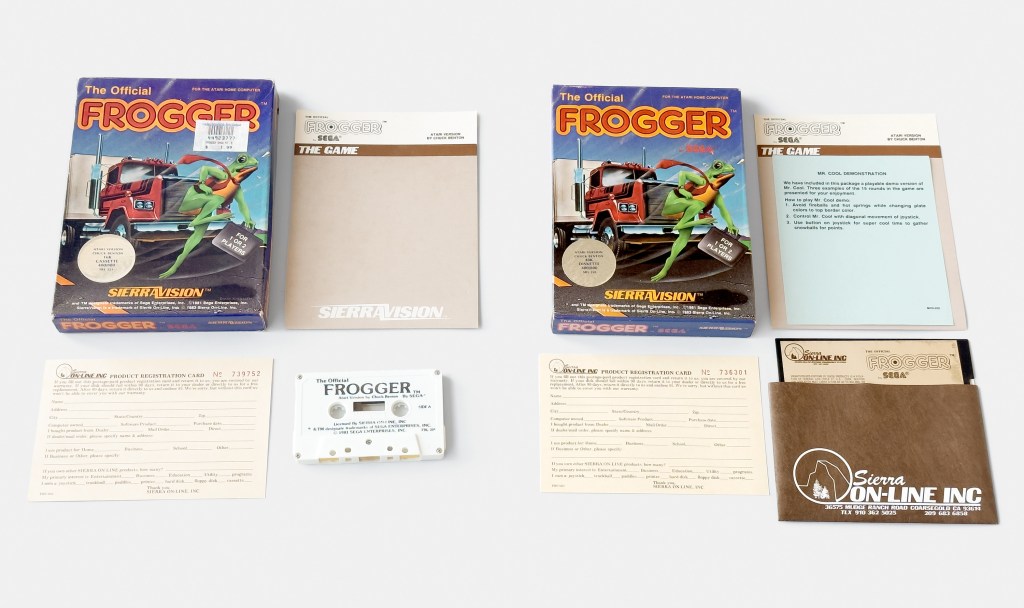

John Harris’ Atari 8-bit cassette and floppy versions of Frogger were published under Sierra On-Line’s short-lived SierraVision label in late 1982.

Development had been rocky, to say the least with Harris having to write the game twice

Despite the setbacks, John Harris’ version of Frogger was nothing short of amazing and extremely faithful to the coin-op version.

Harris’ utilized his friend’s routines for generating continuous music using the Atari’s four voices POKEY chip. The resulting joyful and looping soundtrack only added to an already impressive game with beautiful graphics and smooth gameplay.

Frogger was when released one of the best-executed games for the Atari 8-bit line of computers

Harris’ skills and perfectionistic approach rendered Frogger a superb conversion and an impressive feat, running smoothly with full music and sound. He had managed to faithfully replicate the coin-op version which utilized not one but two Zilog Z80 CPUs on the Atari’s single and now aging 1.79 MHz 6502 microprocessor. While Frogger earned him nearly $40.000 in first month-royalties, impressive sales numbers were not enough to clear the air between him and Williams.

With the introduction of the Commodore 64 in 1982, the consumer market was quickly changing. With the older platforms starting to show their age and a whole new generation of home computer owners embracing Commodore’s latest offering, Williams saw a potential goldmine and assigned programmer Chuck Benton of Softporn fame to create a version for the Commodore 64.

With the Commodore 64 quickly becoming a serious contender in the consumer market, Williams assigned programmer, Chuck Benton to create a version, for the new computer, which was released in 1983

When Parker Brothers approached Sierra wanting to acquire Harris’ code for $200.000 to create a cartridge version for the Atari home computer, things got heated. While Harris was working on a royalty basis, earning him a bit and Sierra a lot, selling the entire code was a completely different deal. The 20/80 split in Williams’ favor, made sense with a final product requiring Williams’ marketing and manufacturing means but seemed quite unfair in this case where the only thing for Williams was to sign the agreement. Harris ultimately proposed a commission deal of 50/50 which Williams firmly and in loud terms declined. Williams wanted to sell the code and then upgrade Harris’ game from one-player to two-player letting his product surpass the competing product from Parker Brothers.

Allegedly he told Harris that he had hired another programmer to do an updated version of Frogger and had called all distributors to return Harris’ version as a new and updated 2-player version was in the works. This meant that Harris’ $40.000 monthly royalties disappeared almost overnight. Accordingly to Harris, Williams never hired another programmer and continued to sell Harris’ version and kept his royalties. There might be some truth to some of it, as Harris’ game continued to be sold but Williams did put Chuck Benton in charge to upgrade Harris’ version with a two-player option along with a few other smaller upgrades.

John Harris’ Atari version of Frogger was upgraded by Chuck Benton to feature a two-player option and released on cassette and floppy in 1983

After the rocky development phase, Williams was looking for an opportunity to out Harris and the latest string of events was the perfect opportunity to get rid of him in a, let’s just say it, not-so-nice way. The fallout with Williams, missing royalties, and the lack of recognition, alongside a desire to work with other Atari developers, led Harris to leave Willams and Sierra On-Line for Atari-focused Synapse Software.

The Apple II version created alongside Harris’ state-of-the-art Atari version by Lubeck was published in 1983. One journalist from Softalk Magazine reviewed it as having as much soul as month-old lettuce in the Sahara. He went on to question the company’s loyalty to its Apple II users, who essentially had helped the company to its success. The Apple II version never managed to become a commercial success and only a small number of copies were sold. While the version was subpar in every aspect to the Atari version it was still a remarkably good game for a machine that was conceived in 1977.

Olaf Lubeck’s Apple II version wasn’t published until 1983 and was subpar to John Harris’ Atari version in every aspect but by Apple II standards it was still a well-playing game. The Apple II was by now six years old and a large portion of Apple II users had already migrated to more capable machines resulting in poor sales

Besides creating the Apple II version, Olaf Luback also created the IBM PC version, released as a PC-Booter in 1983

Following the North American Video game crash in 1983, Sierra On-Line was in dire need of restructuring, and the short-lived SierraVision subbrand was canned. A few of the released SierraVision titles were released now under the generic Sierra On-Line label, including Frogger which was rereleased for the Commodore 64/128, Atari 8-bit, and IBM PC, alongside a version for the newly introduced Macintosh.

For systems not typically supported by the Sierra, the rights were sublicensed to other publishers.

Chuck Benton’s Atari and Commodore 64 versions were released as a combo in 1984 under the generic Sierra name

Sources: Steven Levy: Hackers, Heroes of the Computer Revolution, Wikipedia, InfoWorld, Antic Atari 8-bit Podcast, Halcyon Days, The Sega Arcade Revolution by Ken Horowitz

The Atari version seems even better than the arcade in some respects, particularly the music…

I agree, in my book this is the definitive version of the game.