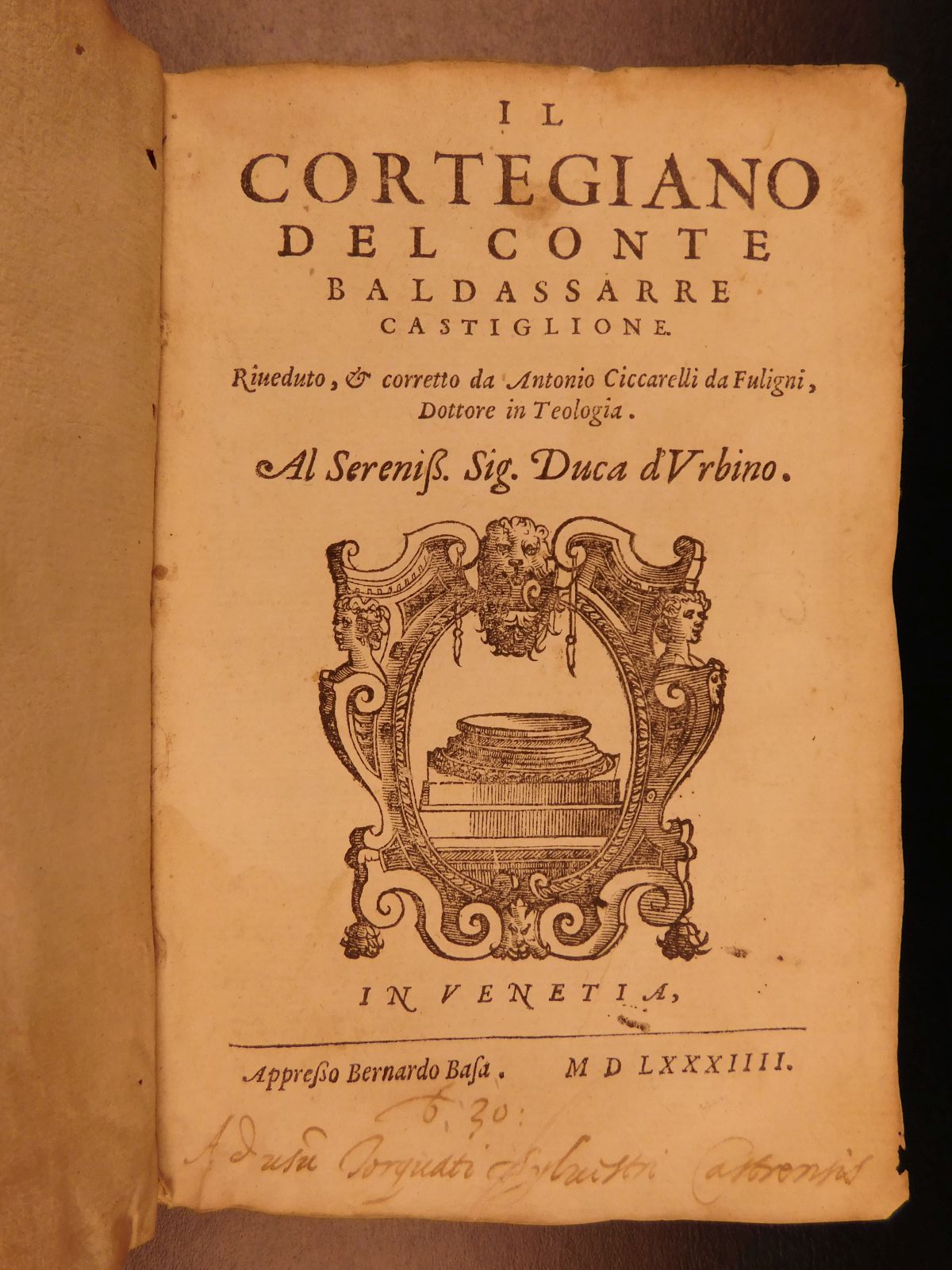

Italian painter Sofonisba Anguissola has received significant scholarly attention for her vast array of self-portraits. As one of the earliest professional artists to create a significant number of portraits of herself, scholars have looked to her works as a way to understand how this remarkable young noblewoman created such a successful career for herself. Sofonisba was unique from other women artists of the Renaissance due to her status as a noblewoman and the fact she acquired her artistic education outside the home. Much of the previous attention has focused on her early career while she was studying and developing her skills under the guidance of the painter, Bernardino Campi, and her later career after she accepted a position to serve Queen Isabel of Valois at the Spanish court. Few have focused their attention to the important turning point in the young painter’s life that occurred in the years leading up to her departure for Spain. In this post, which is a part of my MA thesis project, I analyze one of the last works Sofonisba Anguissola painted prior to her departure for Spain, her 1559 painting, Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola. This painting, like many of her earlier self-portraits served as a way for Sofonisba to promote herself and construct her identity for future patrons. I argue that Sofonisba carefully crafted an identity for herself in this painting as an ideal female courtier, or cortegiana, as described by humanist Baldassar Castiglione while she prepared for the possibility, and eventual reality, of a life at court.

Sofonisba’s early self-portraits were characterized by a simple and modest appearance which made her 1559 self-portrait with Bernardino Campi stand in stark contrast. The most dramatic difference between the double portrait and Sofonisba’s earlier work is her approach to self-representation. In her early self-portraits, Sofonisba wears similar clothing; a simple black dress with a white undershirt. Mary Garrard theorizes that this sartorial simplicity was a way for Sofonisba to graft a measure of masculinity onto her self-conception, for she dressed herself in the common clothing worn by male painters at the time. We can see the simple black smock and white undershirt in Sofonisba’s depiction of Campi in the double portrait. Yet Sofonisba breaks from this trend with her double portrait by showcasing herself in more elegant and luxurious clothes and the addition of jewelry, albeit simple in materials and design. In comparison with her earlier portraits, Sofonisba moved from presenting herself as a masculinized artistic figure, as discussed by Garrard, towards displaying herself as the proper noblewoman. In contrast to her numerous self-portraits which bear many of the same traits, this double portrait stands out as an anomaly or perhaps, as suggested by Joanna Woods-Marsden, a clear progression in the artist’s career. Sofonisba moved from identifying herself as a simply dressed sitter in a static pose to a work in which she identifies herself by her rich clothing and bearing as a female courtier.

Sofonisba’s compositional choices in the double portrait also directly reflected popular conceptions for noble portraiture of women during the sixteenth century. Growing out of the humanist interest in Petrarch’s Laura, images of idealized women became a way for artists to achieve the goals of poetry through painting. This representation of a poised and virtuous woman through elegant and regal posture, clothing, and gesture could be understood as a visual representation of the established ideal woman described by humanists. As humanism and texts such as Baldassar Castiglione’s The Courtier gained popularity, these representations became the way these women could display their education, virtue, and above all, status. Placing Sofonisba’s nobility first in the double portrait can be attributed to the influence of Castiglione, who insists the ideal courtier be of noble birth. If this portrait was the key for gaining favor with potential patrons at court, Sofonisba needed to provide the best first impression. It is her focus on her nobility that differentiates the portrait with Bernardino Campi from Sofonisba’s earlier self-portraits. She is physically separated from the viewer by Campi’s presence and her posture and expression in Campi’s painting are stiff. In addition, she doubles the distance by removing one more level; the image of her is just another image. Campi is more “real” than she is, increasing her passivity in the painting. Garrard suggests on a superficial level this distancing may be a deliberate relinquishing of authority to her former teacher, cancelling out her own pride and ambition by giving the credit to the male artist. Sofonisba visually removes her agency from the painting entirely and his presence takes on greater significance than hers. His presence and action provided external validation of her rank and worth because he is commemorating her in a painting. In removing herself in this manner, Sofonisba emphasizes her status rather than her personality and talent. However, Garrard convincingly argues, she remains the dominant force in the painting.

One of the most discussed, and most perplexing, elements of the painting is Sofonisba’s decision to include her former painting teacher, Bernardino Campi. While double portraits, such as marriage portraits or portraits of male friendship existed prior to this work, it was extremely unusual to have a portrait of a man and woman as acquaintances. Additionally, Sofonisba’s choice to obscure her role as the artist by showing Campi as the painter is even further puzzling to the viewer. Sofonisba had a decade of self-portraits which proudly proclaimed they were made by her own hand. What made the artist decide to include a secondary figure in the creator role and furthermore, why did she choose the secondary figure to be her painting teacher, Bernardino Campi? While Scholars have offered several interpretations concerning Sofonisba’s choice to incorporate Campi into the image, the present study will focus primarily on how his presence reaffirmed her noble status and her identity as the ideal cortigiana.

Sofonisba’s formal education with Bernardino Campi ended nearly a decade earlier, around 1550, so what caused Sofonisba to return back to her former master as a key subject in her painting? The close relationship between the two artists led scholars to understand the portrait as a tribute to Campi. While the homage to her painting teacher may serve as one element of Sofonisba’s goal of the work, viewing the work as a representation of Sofonisba’s court ambitions provides a more complex interpretation of Campi’s presence. To contemporaneous viewers, the painting may have been interpreted as a great Italian artist painting a portrait of a young noblewoman. Sofonisba affirmed her worth as a noblewoman by showing herself being painted by a famous artist. She also distanced herself from the artistic practice. She placed a physical distance between herself as the artist and herself as the subject. Campi physically stood as a barrier between the two versions of herself; the artist outside the canvas painting the portrait and the subject represented on Campi’s canvas in the work. She was not technically even present in the painting, but only as an image created by someone else. In this way, she also concealed her own pride and ambition as an artist by giving authorship of her portrait to Campi.

Sofonisba’s choice to include Bernardino Campi in her double portrait is primarily as a way of displaying her courtly sharp wit. In Book Two of The Courtier, Castiglione calls for the ideal courtier to “know how to sweeten and refresh the minds of his hearers, and move them discreetly to gaiety and laughter with amusing witticisms…so that he may continually give pleasure.” This humor is best illustrated through the manipulation and criticism of the painting’s subject and creator. Mary Garrard’s article on the double portrait examines the theme of the subject/object in the work. She addressed the ways in which Sofonisba understood and then challenged the social expectation of women in portraits as the object of the male artist’s creation. It is in her acknowledgement of this societal expectation that Sofonisba displayed her wit in this portrait. In this way she once again references the poetic portraits of ideal women, she is the female subject as the object of the male artist. In the first viewing of the painting Campi appeared to be the active male character and Sofonisba was the passive female object, yet as Garrard points out the roles are reversed once one considers that Sofonisba is the actual creator of the image. For Castiglione, “the more clever and discreet [the] jokes are, the more they please and they more they are praised.” The complicated web of representation is a way for Sofonisba to playfully critique the expectation of the male creator and the female subject, using Castiglione’s call for the courtier’s wit as the way to criticize.

Perhaps the largest joke in Sofonisba’s painting is at the expense of Campi himself and addresses the theme of the female artist as the creation of the male teacher. In a 1554 letter from the painter Francesco Salviati to Campi, Salviati praised Sofonisba’s skills and abilities and directly attributed them to Campi, for she was his “creation.” While it is not certain that Sofonisba was directly aware of Salviati’s letter, she would have been familiar with the concept of the male creator and the passive female creation. Her portrait replicated the well-known myth of Pygmalion, who brought his beautiful creation to life with his skill and dedication to his subject. Confronting Salviati’s figurative language, Sofonisba placed Campi literally in the midst of creating her on canvas, the portrait is not quite finished, and he put the final details on her gown before he completed his work. Yet Sofonisba also critiqued this idea, for it is the invisible Sofonisba outside the canvas who has created Campi in the painting. Sofonisba also shows a drastic difference in the style and skill of her two subjects. Campi is painted in Sofonisba’s traditional style, the delicate modeling of his features and hands display her skill as a portraitist that received praise throughout her career for breathing life into her subjects. In contrast with Campi, his painting of Sofonisba lacks the quality seen in Sofonisba’s other portraits. The works prior to this painting show the young female artist as carefully rendered, with emphasis placed on her large green eyes and skillful hands. Campi’s painting of Sofonisba is stiff and her left hand awkwardly holds her gloves. Sofonisba may have been attempting to copy Campi’s own style, as the portrait of Sofonisba reflects similar compositional choices as those seen in Campi’s Portrait of a Lady.

The woman in Campi’s 1553 painting stiffly holds her gloves in her left hand at her side and her hands lack the usual modeling seen in Sofonisba’s paintings. The woman also wears earrings comparable to the teardrop pearls Sofonisba appears to be wearing and their hair is worn in a similar fashion. Sofonisba would have been familiar with Campi’s style and attempted to copy it in her painting. By comparing Sofonisba’s self-portraits with the image depicted by Campi’s hand, she purposefully showed Campi as an inferior portraitist. Following in the guidance of Castiglione, the younger artist made “every effort to resemble and, if that be possible, to transform [herself] into [her] master.” She surpassed him, both in skill and notoriety, and became the master. This tongue-in-cheek critique of her painting teacher recasts Sofonisba as the real Pygmalion who breathed life into Campi in the painting. Those who would see the double portrait would have quickly understood Sofonisba’s sharp wit to critique the way she was being cast as Campi’s creation. By 1559, Sofonisba had surpassed Campi’s regional fame and she had gained international acclaim that brought her to the Spanish court by the end of the year. To cast her as Campi’s creation limited her abilities to what he could achieve when Sofonisba had already surpassed Campi’s capabilities by the time this painting was made. The double portrait, while casting Sofonisba as the idealized noblewoman as described by Castiglione being painted by a well-known artist, also contains a courtier’s humor and wit as a way to reference her artistic abilities and success.

Sofonisba placed her nobility at the forefront of her portrait, but she also understood the importance of her artistic ability and inserted references to her talent as an artist. At this point in her career, Sofonisba understood that her nobility alone would never gain her a prestigious position at court. The Anguissolas were minor nobility and Sofonisba’s ambitions to gain a position at a court required something more. What set Sofonisba apart from the other minor noblewomen was her renowned artistic ability. By highlighting her skill and notoriety, Sofonisba proclaimed the worth she could bring to her potential patron’s court. In the double portrait, she casts herself in the position of the poised noblewoman through clothing and posture, but referencing her artistic fame was paramount to advertising herself as the ideal member at court. As mentioned above, Sofonisba alluded to her abilities through her wit and humor by criticizing Campi and the concept of the male creator/female creation. She would have also recognized that through the wit and intellectual humor, the portrait maintained focus on her in order to use it strategically to secure her court position. Visually, Sofonisba is the more prominent figure in the painting. She is significantly larger than Campi and she is positioned in the center of the canvas while Campi is placed to the side of her. The viewer’s eye goes directly to Sofonisba and seeing the work, contemporary viewers of the portrait would recognize Anguissola and make the connection between the young noblewoman depicted and their knowledge of the skilled young artist. Campi’s presence in the portrait became a way of validating and contrasting her skill. Sofonisba had mastered all the skills he taught her, had improved them to reach her current level of success, and her artistic worth had greatly surpassed his. By including herself as the physical subject and the ‘invisible’ artist, Sofonisba was able to occupy two distinct spaces in society and gain artistic subjectivity. She firmly holds the space of the noblewoman subject, claiming and advertising her nobility, as well as carefully and strategically claiming her role as the masterful portrait-maker behind the canvas.

Sofonisba Anguissola’s portrait has been a source of much scholarly inquiry, but it is clear, following Garrard’s pioneering analysis, that visually and contextually Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola is a more complex image than scholarship had acknowledged and required deeper analysis. Viewing the work in the historical context of Sofonisba’s court ambitions and her adoption of Castiglione’s ideal cortigiana, the painting can be better understood as a maturing of a young woman artist’s meditation on societal expectations for women and courtly behavior reflected in previous portraits. She reflected upon the accepted principles of noble portraiture for beautiful young women and casts herself as the young noblewoman painted by the great artist. Yet, she also challenges the conventions of female portraiture by asking the viewer to rethink the ideas of the creator and the creation using her courtly wit and humor. What may appear to be a strange but loving dedication and tribute to her former painting teacher is better understood as strategizing the visual presentation of an elite, educated, and talented young woman. Sofonisba understood her gender placed her at a disadvantage within the traditional art world. She would never be able to follow the prescribed path for the young artist to achieve international fame. Instead of accepting what was expected of her, Sofonisba forged a new unprecedented path by defining herself as a noblewoman and an artist. This new path not only allowed Sofonisba to gain a reputation as a miraculous painter who could breathe life into her subjects, but also allowed her to keep her moral reputation intact by subscribing to Castiglione’s expectations. Her strategic self-portraits allowed Sofonisba to ennoble herself beyond the limits of her minor nobility and she became a model example for many young women artists who followed in her steps.

-Claire Sandberg

To read a full version of this MA Thesis, “Sofonisba Anguissola’s “Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola” and the Ideal Cortegiana,” click here.

Resources:

Baldwin, Pamela Holmes. “Sofonisba Anguissola in Spain: Portraiture as Art and Social Practice at a Renaissance Court,” PhD Dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1995.

Barker, Sheila. Women Artists in Early Modern Italy: Careers, Fame, and Collectors. Edited by Sheila Barker. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, an imprint of Brepol Publishers, 2016.

Castiglione, Baldassar. The Book of the Courtier, edited by Daniel Javitch. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2002.

Ferino-Pagden, Sylvia, Sofonisba Anguissola, and Maria Kusche. Sofonisba Anguissola: A Renaissance Woman. Washington, D.C: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1995.

Garrard, Mary D. “Here’s Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist.” Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1994): 556-622.

Gómez, Leticia Ruiz. A Tale of Two Women Painters: Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana. Edited by Leticia Ruiz Gómez. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019.

Jacobs, Fredrika H. “Women’s Capacity to Create: The Unusual Case of Sofonisba Anguissola”, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring 1994): 74-101.

Musloff, Meghan. “Sofonisba Anguissola’s Double Portrait,” (MA Thesis, Michigan State University, 2003.

Perlingieri, Ilya Sandra. Sofonisba Anguissola: The First Great Woman Artist of the Renaissance New York: Rizzoli, 1992.

Woods-Marsden, Joanne. Renaissance Self-Portraiture: The Visual Construction of Identity and the Social Status of the Artist. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1998.