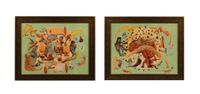

Nalini Malani

Fuelled by her struggles as a female artist in a male-dominated society and influenced by her experience as a refugee during the partition of India, artist Nalini Malani deals with heavy, philosophical topics. Through various mediums, including painting, immersive installations and short films, (which she refers to as video plays), Malani confronts and questions topics that are often avoided and stereotyped. Her works address nationalism from a cynical point of view, the role of the female in contemporary society, current political situations and war.

With a history spanning a childhood in India, to higher education in Paris and residencies in Japan, Italy and Singapore, Malani's art elicits a wide breadth. Both expansive and globally engaging, engendering necessary commentary in our age of globalization, yet disparate social development.

Malani is regarded as one of the foremost contemporary artists from India. She currently has a yearlong retrospective on view at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi and an exhibition of her work Transgressions is at the Asia Society in New York through August. In this conversation she talked about her background as well as recent inspirations and philosophies toward life and art.

EMI'm interested in your inspirations and how you've moved between different mediums, but can we start with how you first became interested in art?

NMIt was actually through my biology teacher that I got interested in drawing because she was able to, in a very lucid way, show the systems of nature, which were invisible. My motto was to make that which is invisible visible and to find forms that are invisible but very essential parts of life.

EMDo you think you still use biology in your work now?

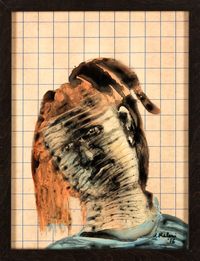

NMIt's the same idea of trying to make that which is invisible visible. For example, people's psyches and aggression between people. Also, I'm very interested in drawing the organs of the body and things in nature because those carry a lot of weight in terms of thought processes and ideas. We tend to think that ideas only come from the mind, but I think other sections of the body also carry ideas and thoughts.

EMWhat other sections of the body do you find yourself drawn toward?

NMThings like the skin, for example, as being the boundary between two bodies and how things are confined within the skins of people. Skins become exclusive to one and other in terms of sectarian issues and racism and there is a sense of people who are dispossessed. The skin becomes that boundary, and then that boundary extends to boundaries of nations and different concepts of life. It is a paradigm I use to try and understand what is happening around us. That is why I seek to work in art.

EMYou refer to your videos as video plays rather than films. Why do you think you do that?

NMI have a passion for theater but it's not really possible to work in theater in India because there is no state support and there are scarcely any private situations where one can work in theater. It's a very difficult and expensive art to perform. I thought the easiest [way] would be to work with performers, but to have them on video. It's easy to carry around and show at various venues. Hamlet Machine, one of the video plays I made in 2000, has been shown in 17 countries around the world.

EMWhen did you become interested in theater?

NMI had my first studio in Bombay—this space in a huge bungalow, which a private foundation had given out to different artists, including theater artists, musicians and dancers. I had just joined art school and was very lucky to have met a dynamic, young theater director, who with a poverty of means was creating this wonderful environment with new writing in India. That was a revelation and inspiration because new writing in India took a lot from the epics and myths. That became the linked language to connect people and the conduit for conversation.

Later on in the visual arts, I used the same metaphors. If I cited a particular mythological figure, immediately the myth would connect. I wanted to bring it into the contemporary fold and myths allowed for that, just as we know Greek myths allow for contemporary readings.

EMI noticed a lot of your work deals with mythology. Is there one myth you find yourself returning to repeatedly?

NM There are two particular Greek myths I keep returning to and there are resonances in Indian mythology [that are] quite similar. One is Medea and the other is Cassandra.

Medea because she is a difficult figure, even to perform. When she finds [out] she's been betrayed, she de-genders herself and destroys her children. The only way she can do that is by saying the two children are Jason's children, not hers. By distancing herself from being a mother, she can avenge herself against Jason. There is a figure of that nature in Indian mythology. Her name is Sita.

Then there's Cassandra. I think she represents female instinct and thought, which has a sense of the future. She tells her father about the Trojan horse and to not let the horse in because the Greek army is inside. Of course, he does let them in and Troy is destroyed. The fact is, Cassandra had the gift of prophecy, but Apollo cursed her because she refused his advances. He said, "You will have the gift, but nobody will believe you." The Cassandra and Apollo concepts exist inside all of us, male and female. If we paid more attention to the Cassandra aspect of ourselves, I think we certainly [would] know what's right for the future.

EMYou're very tuned in to political affairs as well as mythology. What has been your inspiration in recent works?

NMI have a three-chapter retrospective at the moment in Delhi that runs for the whole year. In this period I want to go into a sabbatical to start working on the next project, which will have myths turning up, but I'm curious to examine how types of music have come to us through courtesan culture. It was the courtesans who preserved a certain kind of female vocal music, because the householder was never allowed to indulge in the creative arts—music, poetry, dance or the visual arts—prior to the British coming to India. The courtesan had a certain status in society and was respected because she held the culture of the woman. There was an intimacy between the women courtesans who were intellectual; they discussed ideas. People think it was only men doing these things. I want to dig into this past, work on an immersive installation, and write a fictive story about this part of South Asian culture.

EMA lot of your works deal with the power of women. Do you consider yourself a feminist?

NMThe thing about feminism is that you say you're so-and-so—your a Marxist or a feminist—and it's put in the drawer and forgotten about. So I prefer not to. I prefer open-ended things. I believe feminism will come into it's own when I hear men speaking about these problems as their own. I'm waiting for that moment.

I'm interested in digging, in that adventure of finding how all of this works. Why is the whole thing so skewed? That we are not agents of our own destinies? That it's an oligarchy of men who decide our destinies? Whether [or not] to go into Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan or India—all of these things are decided by an oligarchy of men. Women are left with wounded or dead children who play in minefields. This is not something they had ordained. They had not wanted this war; they had not wanted wounded children. As long as males do not think feminine thoughts as well, it's not going to resolve.

EMDo you still consider The Partition a significant influence in your work?

NMI use The Partition of 1947 as a warning signal. You have to remember history or you repeat it. In the Indian Subcontinent there are sectarian issues that keep popping up and there is bloodshed. It's like another little partition that's taking place. I think the violence of one human being on another is so regressive in this age of technic development. We've progressed so far, [so] why is it that the human mind doesn't progress and get over these medieval ideas of your religion is better than mine? It's a bit like what Hannah Arendt said: Does one need to resort to killing to get ideas across? Is that progress? Why kill? Does one have the right to take life?

EMWhen you deal with such tough topics, what do you do to escape?

NMI use seduction in my work. The first encounter I want is that of beauty and I use that device to draw in the spectator. Then I unfold a story, which will have its ups, downs, and contradictions. Painting and drawing for me are like a keyboard would be for a composer. I love to paint, [but] then I move out to other areas—the immersive painting or shadow play. The subject may be heavy, but I open up the whole thing so we can speak about it together. Artwork is a relationship between the viewer, the artwork, and me, the artist. Only then the art lives. Otherwise it is dead behind doors.

EMSo how do you personally deal with tough topics? What do you do to keep yourself grounded?

NMJust as a novelist tries to shape certain characters I think it's the form that keeps the artist going—to find form, to find the vehicle of how something can be conveyed. Part of making the artwork is an alienation situation. You have the space to think things through. You have space for thought that you create yourself. You can't make an artwork if you're completely in it. If you're in the whirlpool, you're drowning. You have to be out of the whirlpool to be able to look at it and then you can do something about it.

EMThat's a difficult thing to do.

NMIt's difficult, but I do so many things. Most of my subjects are too wide, too large for them to be contained in one artwork so it goes on and on. I make joint books; I make storyboards; I make flipbooks; I make animations. The subject goes into several different forms.

EMGoing back to you being a female artist in India—what are some of the biggest struggles you have overcome?

NMThis is an extremely male society. When I told my parents that I wanted to go to art school they thought I was crazy. My father wanted me to have a university degree. He said, "The only thing that is going to help you is a good education. They may throw you out of here and then what will you do?" At the time, doing art was not a university course. It was like having a diploma in plumbing or being an electrician. He thought it was very, very stupid of me for thinking about doing art. He said there is no such thing as a woman artist and he was right! There was no such thing as a woman artist when I started. I was very lucky to get a good scholarship to go to Paris. There I felt fulfilled by what I saw around me, but in India I was a very rare breed.

EMWhen did you first become accepted as an artist in India?

NMI don't think I'm even now accepted.

EMReally?

NMThe strange thing about India and Indian myths is that on one level the woman is treated is like a goddess and on the next level she's treated like a doormat. It's this terrible swing that one is working against. It's about time that people look at women as ordinary human beings with senses and thoughts instead of in these extreme ways.

EMHow would you describe your philosophy toward art?

NMFor me, it's always a quest, research and trying to key in ideas. It's an adventure and trying to find out. I often feel very uneducated so I educate myself all the time. It becomes a process [of] finding material that can convey the research I found so interesting. For me, that is what art really is. —[O]