by Helen M. Rozwadowski and Gard Paulsen

This spring Helen Rozwadowski had the opportunity to spend three months as a guest researcher at the University of Oslo, working on the Maritime Modernities project. Visits to maritime museums were an integral part of our explorations of the maritime past. This blog post includes two sets of comments on The Whaling Museum (Hvalfangsmuseet) in Sandefjord, Norway, one by Rozwadowski and, following that, one by Gard Paulsen, a Norwegian who has dabbled with the history of whaling. The town of Sandefjord, and the Vestfold region where it is situated, formed the center of the international whaling industry from about 1905 to the post-World War II period. The majority of whale ship owners and crew for the entire industry, which expanded rapidly in the Antarctic seas in this period, came from this area. The industry at that time used all parts of the great whales that were its target, but the main product was whale fats which were delivered to refineries around the world and used to make numerous industrial products, of which margarine was the most important.1

Helen M. Rozwadowski:

One of the most interesting maritime museums I visited during my time in Norway with the Maritime Modernities project was the Sandefjord Whaling Museum. I should explain that I live less than ten miles from the Mystic Seaport Museum and make occasional visits to the New Bedford Whaling Museum, so my knowledge of whaling history is focused on the wooden ship era of the nineteenth century, which extended a bit into the twentieth. I was eager to learn more about industrial whaling and I was not disappointed. I’m also a museum fan in general, with an interest in the history of museums. For that particular species of museum geek, parts of the Sandefjord Museum offer a fascinating time capsule. Finally, I discovered that whaling history spilled beyond the walls of the museum building. In fact, the entire town is like a museum, filled with artifacts and memorials to an industry that was so intertwined with Norwegian history.

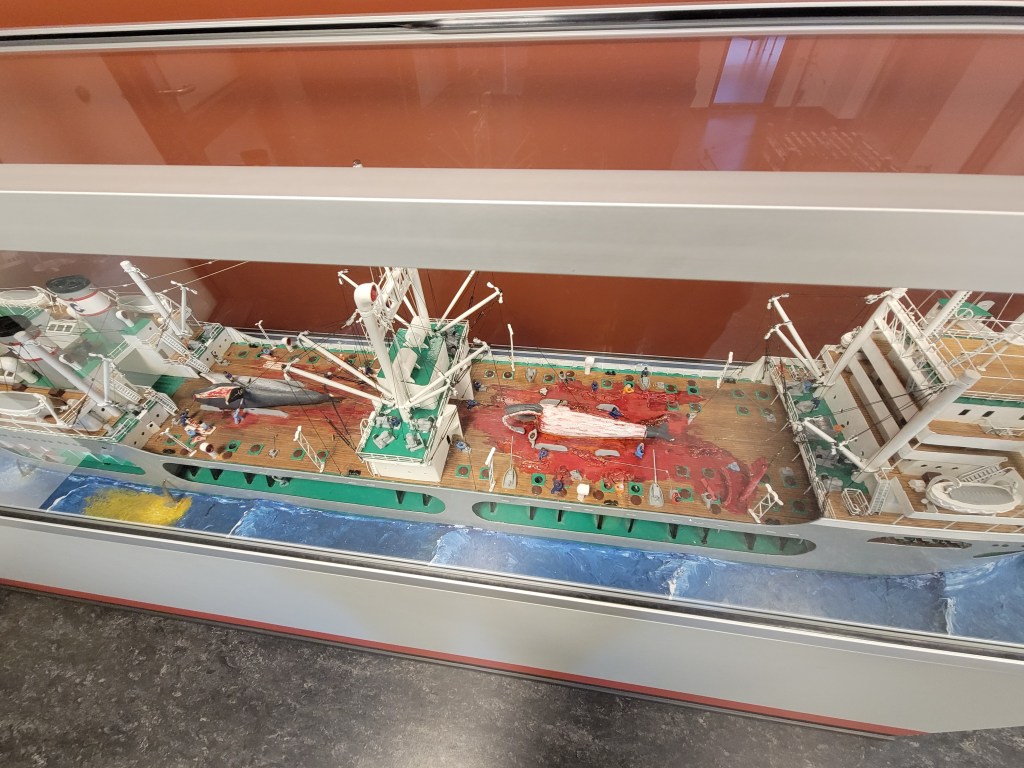

The museum was founded in 1917 by Lars Christensen, a whaling ship owner who named the museum “Commander Chr. Christensen’s Whaling Museum” after his father. The museum includes the original building, with a large wooden model of a whale hanging from the ceiling in a hall with a second-floor gallery around the open central area. There are display cases of taxidermized Antarctic animals and dioramas depicting the natural history of that region (yes, including penguins). Wedged into a basement area are several whale skeletons and skulls that seem likely to have been more prominently displayed in the past. Visitors are encouraged to start their explorations in the newest building and exhibit area, with display cases, signs, and artifacts that provide an overview of the Sandefjord whaling industry and the importance of whaling to Norway more generally. A highlight here was the attention to Norwegian whaling and the geopolitics of the Antarctic region. The display case documenting Lars Christensen’s opportunity to shoot a whale himself – and the connection drawn there to his big game hunting activities in Africa – reminded me of Gary Kroll’s story about Roy Chapman Andrews persuading a Norwegian gunner to let him shoot a whale with a harpoon cannon in 1909, an experience he understood in the context of the ultimate in trophy hunting.2 Most surprising to my American eyes was the frank portrayal of the violence of whaling. A model of a whaling ship with a stern slipway, depicting the processing of whale bodies, was awash with bright red blood. (See Figure 1)

A film running on a big screen on the top floor of the museum matter-of-factly included an enormous amount of footage of shooting and processing whales. A few years ago, I had looked for photos showing the reality of twentieth-century industrial whaling for a book illustration and had a hard time finding one. Clearly, I should have contacted this museum. The museum buildings and displays still bear the imprint of beginning as the project of one family, with some modernization and contextualization of this major Norwegian industry. Perhaps its greatest fascination for those interested in museum history lies in the glimpses of changing interpretations of whaling over time.

Evidence of the original museum is easy to find today. The sign outside the hall with the whale model bears the initial name of the museum in hand-done lettering with art nouveau style decoration. (See Figure 2)

The whale model was built in the hall as part of the original construction. Although the natural history displays and dioramas also date from early in the museum’s history, the present focus on ecology is certainly more recent. (See Figure 3)

Based on my knowledge of the Mystic Seaport Museum, founded in 1929 to collect and display artifacts from America’s whaling past, I would have expected to see more implements and tools from whaling. It would be wonderful if someone could tell the history of this museum and how its interpretation of industrial whaling changed over the years, as Jason Smith has done for the history of the interpretation and reinterpretation of the wooden whaleship Charles W. Morgan from its arrival at the Mystic Seaport Museum in 1941, when it symbolized individualism and free enterprise, to the emphasis on a multicultural society that emerged from social history through its “38th voyage” in 2014, when the vessel visited ports in New England as an “ambassador to whales.”3 The Sandefjord whale model itself seems well worth investigation, especially in light of the comparative history that Michael Rossi has done on whale models in the US, both the 1907 blue whale model made at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and the model made in the 1960s for the updated Ocean Hall. (See Figure 4)

Rossi’s history suggests that the model in Sandefjord was based on knowledge and experience of dead whales.4 In sum, those interested in how whaling history is remembered will find the museum rewarding, but would find a stroll through town equally so.

A visit to the town of Sandefjord isn’t complete without a stop at the Whaler’s Monument (Hvalfangstmonumentet), a dramatic memorial created by Norwegian sculptor Knut Steen and placed in 1960 at the head of the fjord and the foot of the main street through town. In the center of a large fountain with water columns of varying heights – and lighting from under the water at night – a bronze statue of an open whaleboat being raised into the air by a whale’s tail rotates slowly. Granite friezes of scenes from industrial whaling flank the fountain and beyond are metal fences with stylized Antarctic penguins, seals, seabirds, and fish.5 But whaling history lurks everywhere, not just at the memorial. The large bank in the town square testifies to the profitability of the industry for the town. The harbor-side Scandic Park Hotel, which opened around the same time the fountain was completed, originally bore the name The Whaling House (Hvalfangstens Hus) and included whaling company and industry offices on its top floors. Today an arch made from a blue whale jawbone still sits outside the hotel. (See Figure 5).

Walking along the coast brings a visitor to more than one harpoon gun, some placed in parks and others at business buildings. (See Figure 6). Large objects related to whaling, like the claws that drew whale bodies up the sterm slipways of whaling ships, as well as whale bones, capstans, pulleys, etc., lie in parking lots, in front of or behind buildings, very much like abandoned harbor cranes are left in place in ports like Hamburg when outdated port facilities are transformed into residential areas. The ubiquity and visibility of whaling artifacts throughout the downtown area suggest local pride and an ongoing town identification with the industry.

The most astonishing find, though, was the enormous collection of whaling tools, artifacts and scrimshaw at the Clarion Collection Hotel Atlantic, not far from the main square. There were easily more artifacts here than on display at the museum, including four large glass cases stuffed with whale bones, otoliths, eyeballs, and many, many pieces of scrimshaw. (See Figure 7)

Harpoon gun shafts were repurposed for outdoor stair railings. (See Figure 8) The hallways held harpoon guns, a large model of a shore whaling station, and a mannequin dressed up as a whaler leaving for the season, with his open sea chest to show what he brought with him. Outside and within the breakfast area were whale jaw bones, radios, emergency gear, and other artifacts packed into every available space. There were no labels or explanatory texts, and the hotel staff could only tell me that the hotel building is owned by the person who owns this collection. I spent some time looking at the scrimshaw and observed that each case had multiple examples of whale teeth or pieces of bone upon which twentieth-century Norwegian whalers had carved “Moby Dick” or something evoking Herman Melville’s tale. One artist had inscribed “Kall meg Ismael,” prompting me to wonder about how these whalers saw their work in relation to their nineteenth-century counterparts. (See Figure 9).

This collection, the town of Sandefjord, and the Whaling Museum together offer rich resources for whaling history, perhaps even richer for delving into how a powerful and lucrative, but destructive industry was remembered, and how that memory has changed, or not so much, over time.

Gard Paulsen:

While I am a Norwegian historian interested in the history of whaling, I must admit that I am no regular at the Whaling Museum of Sandefjord. And contrary to Helen, I am not a particular fan of museums. As such, it might seem a bit unfair that I should add to the above review. However, after comparing notes with Helen after her recent visit to the museum, I looked back at a visit on my own a year ago. It became apparent that, although our takeaways from the visits were quite similar, they transpired for quite different reasons. Indeed, rather than being struck by everything there, the artifacts, the remnants, the buildings, and the whaling history lurking everywhere in the city, I was surprised by all that was not there. By this, I do not imply that the city has lost its whaling history, or that the museum lacks historical detail. Rather the opposite. There are quite enough details, I think.

What struck me most was that the industrial scale of the whaling that emerged out of Sandefjord at the beginning of the twentieth century and which continued to dominate the industry, is so hard to grasp. While I meandered around the most recent addition to the Whaling Museum, attending to aspects of whaling that relate to international relations, political history, social history and labor relations, I tried to understand just what some typical measurements of whale oil actually amount to, a barrel, a ton, the total whale oil produced over a season. That was perhaps not the intended effect of the exhibition, but that was what I kept thinking about. When I walked around the original hall of the museum, the one with the wood-made model in the ceiling, I even tried to envision how much oil a whale of that size would produce and how much oil it would take to fill the whole room. Furthermore, when thinking about the history of whaling, I am always left wondering about the “end product”, primarily the various kinds of oil. On the balcony of the original hall, some remains of your typical whale oil products were exhibited. But this comes across as one of the oldest parts of everything inside the museum, other than the whale bones and the taxidermy. Still, it was almost as if there were no end-products.

While whaling industry participants often liked to portray themselves as explorers, and the operations were always called expeditions, the planning, the regularity of the kill, the effectiveness of the carving up of the animals, the machinery, the system-like nature of it all, that is what is all so difficult to get a grip on. And that is, of course, a grip that is needed to understand how intense whaling drove many of the world’s whale species close to extinction. How to exhibit that, I am still left wondering, even after a visit to the museum of the city that pioneered it all.

Furthermore, while Helen found the portrayal of the violence of the whaling frank, I found it almost non-existent. I know, there is footage, and there is blood in a model. There are even movies. But the sheer scale of the violence, the constant production of violence, that is something that is just not there. I mean, on the deck of the largest floating factory out of Sandefjord in the immediate postwar period, more than 50 whales could be “processed” over 24 hours. What I was looking for is not an industrial museum detailing the evolution of the processing of whale blubber, meat and bones into oil, but some way of grasping the different relationships between the city, its whaling interest, the workers, the products and the animals.

Here, I must admit that my idea of a righteous whaling museum would perhaps not be something anyone would like to visit: I keep envisioning how powerful it would have been if all the visitors were forced to wear hipboots, and wade through blood, fats, oils and guts, on a deck heaving and swaying – while all of those visitors were simultaneously tasked with calculating the profit margin of selling 100,000 barrels of low quality, dark and stinking whale oil. I know, bad idea.

In general, I agree with Helen: When visiting Sandefjord, it is hard not to be struck by the whole whale-ness of the city. The whaling history really does lurk around everywhere. This is, of course no surprise: In a sense, even though only for a brief period of time, Antarctica was a place in Vestfold, while Grytvigen, the origin place of modern industrial Antarctic whaling, was not a bay at South Georgia, but one that was as if located in Sandefjord’s fjord. This had all kinds of consequences: I mean, penguins did not only end up taxidermized in the whaling museum, but they were also brought back alive from the Southern seas, only to live in an all-too-warm private garden of the whaling aristocracy of Sandefjord. In the 1930s, luxurious American cars were rather common in the city, mirroring the sudden riches of some, while the booms and busts of industrial whaling could just as well bring sudden unemployment to workers. In the 1960s, however, Antarctica was no longer a virtual suburb of Sandefjord as industrial whaling was increasingly a losing proposition. It faded away to memory. Despite everything that is lacking, or perhaps just because of it, I too find the whaling museum and the city of Sandefjord excellent places to visit when considering how whaling is now remembered.

- For background, see J.N. Tonnessen and A.O. Johnsen, The History of Modern Whaling, translated by R.I. Christophersen (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), [chapter 10-22??]. ↩︎

- Gary Kroll, America’s Ocean Wilderness: A Cultural History of Twentieth-Century Exploration (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas), pp. 9-36. ↩︎

- Jason W. Smith, “Thou Uncracked Keel: The Many Voyages of the Whaleship Charles W. Morgan and the Presence of the Maritime Past,” New England Quarterly LXXXIX(3)(2016): 421-456. ↩︎

- Michael Rossi, “Fabricating Authenticity: Modeling a Whale at the American Museum of Natural History,

1906–1974,” Isis 101(2)(2010): 338-361. Rossi, “Modeling the Unknown: How to Make a Perfect Whale,” Endeavour 32(2)(2008): 58-63. A popular article chronicles the Smithsonian whale models: Smithsonian Ocean Team, “A Century of Whales at the Smithsonian,” Smithsonian (April 2019); access at https://ocean.si.edu/museum/century-whales-smithsonian. ↩︎ - There are pictures of the fountain here: https://www.visitnorway.com/listings/the-whaling-monument/3303/. ↩︎