The Grit That Makes the Pearl 26 May 2023

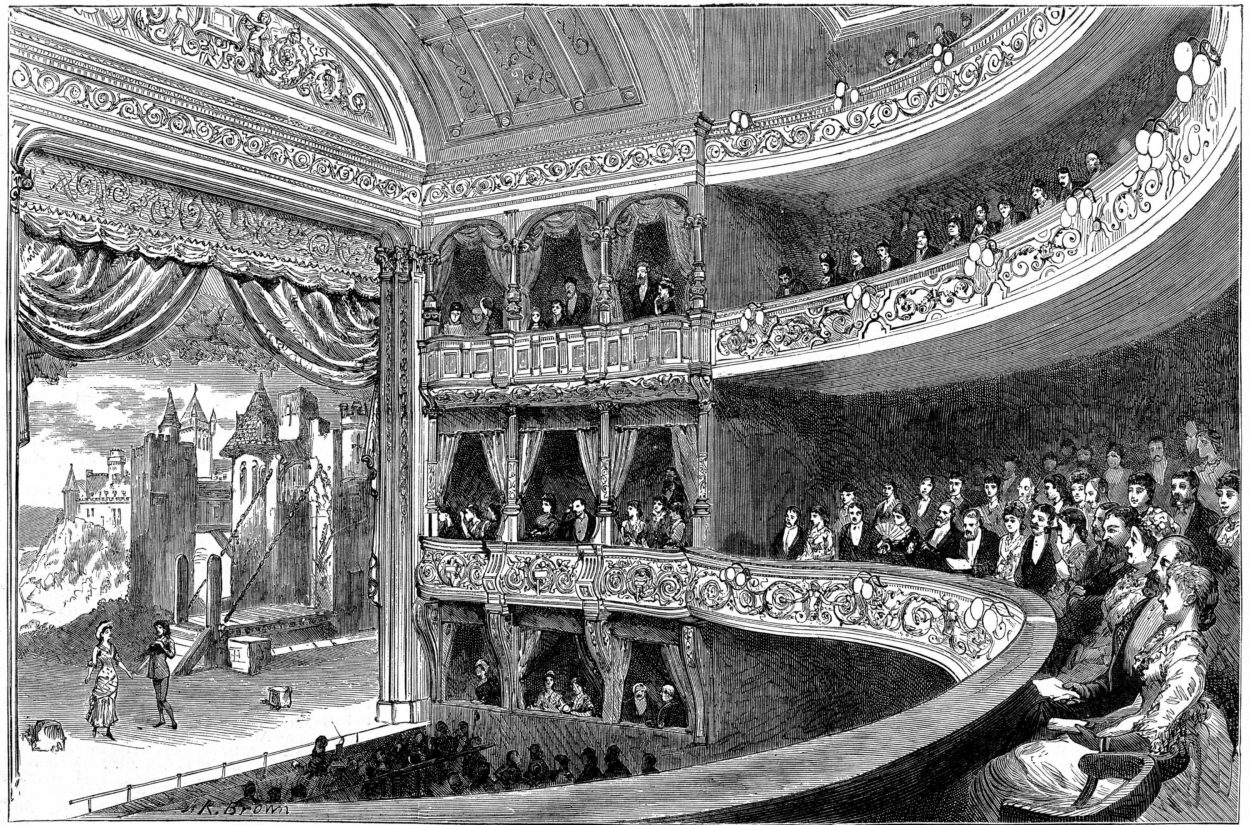

Savoy Theatre, London. House, not stage, lit by Swan incandescent electric lamps. Built by Richard D’Oyly Carte in 1881, it was the home of the Gilbert and Sullivan operattas. Wood engraving, 1881 Universal History Archive/UIG / Bridgeman Images

Savoy Theatre, London. House, not stage, lit by Swan incandescent electric lamps. Built by Richard D’Oyly Carte in 1881, it was the home of the Gilbert and Sullivan operattas. Wood engraving, 1881 Universal History Archive/UIG / Bridgeman Images

In the spring of 1883 Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe was in the middle of a triumphant first run at Richard D’Oyly Carte’s Savoy Theatre. Carte had already astonished London by lighting his brand new theatre with electricity – a world first. Now he introduced a new innovation: a marshalled queuing system on the pavement outside, to help contain the enthusiasm of the crowds who flocked every night to see the smash of the season. Carte wasted no time signing his star writers to a new contract, requiring Gilbert and Sullivan to supply him with a new work at six months’ notice for the next five years. Feeling flush, Gilbert leased a country house near Pinner for the summer, and Sullivan visited him there to discuss their next project and play tennis. Spectators noticed that Gilbert “arbitrarily extended the regulation measurements of a tennis court to allow him to get his service in”.

Princess Ida was the opera that they discussed between volleys, and you might say that Gilbert employed rather the same technique there too. The pair were committed to their partnership, but Sullivan had lost heavily on the stock exchange the previous autumn, and didn’t have much choice. Meanwhile in May 1883 he’d been knighted for his “distinguished talents in music”. Comic opera was now deemed to be beneath him. “Some things that Mr Arthur Sullivan may do, Sir Arthur Sullivan ought not to do” sniffed the Musical Times. Already, Sullivan had been chafing against Gilbert’s taste for magical plots and “topsy-turvy” comedy. But work on the new opera (Gilbert and Sullivan never used the term “operetta”) was already in progress, and it was clear that Gilbert was offering something different. With its three act structure (unique among their collaborations) and blank verse libretto, Princess Ida was the closest the pair had yet come to creating a conventional opera.

And like many conventional operas, it was based on a pre-existing work, Tennyson’s humorous narrative poem The Princess (1847). Gilbert had already given The Princess the once-over in 1870: a comic reboot in his own satirical style, with songs set to melodies borrowed from (among other works) Offenbach’s La Périchole and Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Now Gilbert adapted large stretches of The Princess for Sullivan’s use, and Sullivan liked what he read. “2nd act in good order – only wants a song for the Princess” he noted in his diary, around the time of that tennis match. “3rd act very nearly complete – left 1st act with [Gilbert] to make some alterations. Like the new piece as now shaped out, very much”. Rehearsals commenced in November; Sullivan worked through the night on Christmas Day to complete a new quintet for Act Two (he preferred to work in the early hours, when night offered some respite from London’s constant traffic noise).

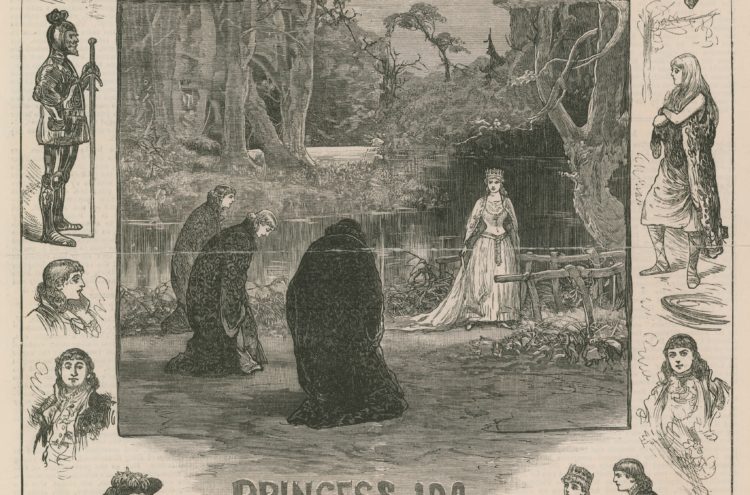

Iolanthe closed on New Year’s Day 1884, and Princess Ida, or Castle Adamant opened less than a week later on 5th January – with an exhausted and rheumatic Sullivan dosing himself with morphine and black coffee so that he could conduct the first night. It looked like a triumph: “the best in every way that Sir Arthur Sullivan has produced, apart from his serious works” declared the Sunday Times. “Humour is almost as strong a point with Sir Arthur Sullivan as with his clever collaborator, and when attained by such legitimate means it is simply irresistible”. Irresistible, that is, until it wasn’t. Within two months, the box office was flagging. It was clear that Ida was not going to be another Iolanthe, and when Carte duly submitted a request for a replacement within the statutory six months, Sullivan had already told friends that he had decided “not to write any more Savoy pieces”.

How the pair extracted themselves from that particular corner is another story (or you could just watch Mike Leigh’s Topsy-Turvy), but Princess Ida has never quite shaken its early reputation as one of Gilbert and Sullivan’s also-rans. Matters weren’t helped by a catastrophic 1991 revival at ENO in which the film director Ken Russell relocated the action to a sushi bar inside a futuristic Buckingham Palace. Meanwhile Princess Ida has become a special favourite of diehard Savoyards, many of whom (present company included) maintain that it contains some of the pair’s very finest inspirations. Its subject matter has worked against it: to a modern audience, Ida’s all-female university isn’t self-evidently laughable, and Gilbert – in poking fun at the founding of Girton College Cambridge (1869) and (even more topically) Westfield College in Hampstead (1882) – was certainly indulging the popular prejudices of his era.

But Gilbert was nothing if not an equal-opportunities offender. If pioneering female scholars come in for a thorough leg-pull, so too does Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and – the one unvarying butt of Gilbert’s mockery – the complacent, pompous or just-plain-stupid male authority figure. The true target of Princess Ida’s satire is not idealism itself, but idealism untempered by realism: a logical premise carried to ludicrously illogical conclusions. The preposterous King Gama and his thick-as-mince sons can’t – and won’t – change.

In Princess Ida, however, Gilbert creates a character – rare in any satire – who learns and grows, and Sullivan gives her some of his most heartfelt music. The comic G&S are sparking at full power in the first and third acts: witness Gama’s If You Give Me Your Attention (one of their most mischievous list-songs) or the deadpan mock-Handel of This Helmet I Suppose. But in Act Two, from the Mendelssohn-like delicacy of Toward th’Empyrean Heights, through Ida’s noble (and wholly sincere) opening invocation Oh, Goddess Wise to the ravishing, bittersweet quartet The World is But A Broken Toy – and then on to the sparkling quintet The Woman of the Wisest Wit – the joint creativity of both Gilbert and Sullivan is at its peak, with a string of melodies unsurpassed even by their great continental inspiration (and rival) Offenbach. It’s been described as “Sullivan’s string of pearls”: on period instruments those pearls will glint as radiantly as the day when they were picked.