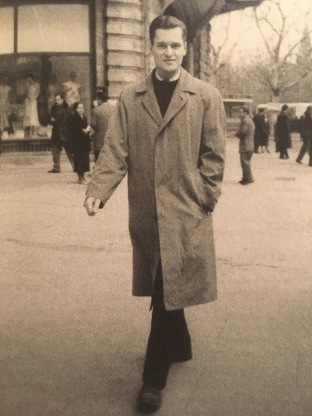

John Ashbery, fall 1955, after arriving in Montpellier, France to begin his Fulbright.

Karin Roffman’s new book, The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life — the highly anticipated, first full-fledged biography of Ashbery — was recently published, and my review of the book appeared in the New York Times Book Review several days ago. As I write in the review:

like a classic bildungsroman, The Songs We Know Best tells the story of a shy, sensitive, preternaturally gifted boy who weathers a lonely childhood on a farm, awakens to the joys and mysteries of art, poetry and sex as a teenager, and finally assumes his true vocation as a poet when he arrives in the big city and falls in with a circle of revolutionary writers and artists. It is also an affecting narrative about growing up gay in a virulently hostile, intolerant culture — a moving portrait of an artist who not only survived that ordeal as a young man but became, improbably enough, one of the greatest poets of his age.

Thanks to Roffman’s “exhaustive research — especially her deep dive into unpublished early poems, newly uncovered diaries and extensive interviews with Ashbery himself,” the book is “a treasure trove for scholars, fans and casual readers alike.”

Indeed, the book is crammed with illuminating and fascinating new details that will surprise and delight even those of us who know Ashbery’s work, and the criticism of it, well. Among other things, the book unearths a good deal of personal, even juicy material about Ashbery’s private life, including his early crushes and romantic relationships (giving us moments like this one, which may be a little TMI for some: “he and Dick Sanders hugged, kissed, and fondled each other, and John ejacluated for the first time”).

Here are just a few of the many little tidbits from the book that I enjoyed but didn’t get a chance to mention in my review:

~ Roffman reprints and analyzes the absurdly precocious poem called “The Battle” that Ashbery wrote at the ripe old age of 8 (opening lines: “The trees are bent with their glistening load, / The bushes are covered and so is the road”). She explains that the poem was a huge hit with Ashbery’s parents and extended family and even made its way from rural western New York where Ashbery grew up to the exotic foreign land of Manhattan, where the poem was recited to great praise at the apartment of a famous novelist named Mary Roberts Rinehart. Once young John was “informed of his poem’s journey to NewYork City and told that it had received great acclaim, he felt inspired to write more.” But, alas, it was not to be: the poor little guy was unable to recreate the magic and simply could not write a new poem, so “he decided to quit writing poetry altogether” and didn’t write another poem for 7 years!

~ Ashbery gave Roffman access to a diary he kept as a teenager, which no previous scholars have seen or referred to, and not surprisingly, it is a goldmine of information about the adolescent Ashbery: wry meditations on the boredom of life on a rural farm, thoughts about art and literature, cryptic notes about his early infatuations and trysts with boys (sometimes written in Latin or French to throw his prying mom off the scent), along with wonderful comments that presage the poet he would become — like when he recorded in his journal that he was “doing nothing vigorously,” which seems so quintessentially Ashberyean.

~ The book includes a revelation that I don’t believe has been disclosed before: Ashbery had a brief and very stormy romantic relationship with the painter Fairfield Porter not long after meeting him in the early 1950s. Ashbery and Porter later became very close friends, but I can’t recall previous references to the fact that their relationship began with a sexual encounter. Roffman notes that after they slept together in Porter’s studio, “John immediately felt he had made a terrible mistake”; Porter quickly developed a “fixation” on Ashbery, became “antagonistic” when Ashbery rebuffed him, and told Jane Freilicher that “he wanted to leave his wife, Anne, for John.” Then things got even more dramatic: “John refused to see him. Miserable at being cut off, Fairfield punched John when he saw him unexpectedly at the San Remo Café.” Only months later were Ashbery and Porter able to “repair their friendship after the fumbled intimacy.”

Justin Spring’s biography of Fairfield Porter (2000) broke new ground by discussing Porter’s largely hidden bisexuality for the first time, detailing the extended sexual relationship he had with James Schuyler. However, in that book, Spring merely notes Porter’s early attraction to Ashbery and discusses a poem called “The Young Man” that Porter wrote for Ashbery, which quietly expressed his homoerotic feelings for the young poet. But Spring says nothing about their having slept together and how it affected their relationship, so the revelation in Roffman’s book is news.

~ Here’s another juicy bit that I don’t recall being divulged before. It’s well-known that Ashbery got a chance to meet his idol, W. H. Auden, during his time at Harvard, but apparently their bond went a little further than is often assumed: during a visit to Harvard, Auden attended a Harvard Advocate event, and the two “chatted a while, and then Auden invited John to walk with him back to his hotel suite. After accompanying him as far as his room, however, John demurred. Despite his boundless admiration for the man as a poet, he ‘could not go to bed with him’ and returned to his dorm room, where he described the almost-sexual encounter” to a friend.

The following year, Ashbery decided to write his senior thesis on Auden’s work, but had a very difficult time completing the essay. Procrastination, a lack of motivation, and depression left him unable to write the thesis; Roffman also touches on “the difficulty of writing about a gay artist (and near love interest).” Imagine trying to write a senior thesis on a famous writer, who wanted to sleep with you, and who you rejected!

~ The book includes a few more details about Auden and Ashbery that were new to me: six years later, Auden would of course choose Ashbery’s manuscript for the Yale Younger Poets Prize (passing over Frank O’Hara’s manuscript in the process), an award which led to the publication of Ashbery’s first book. That much is known, but apparently it was Auden “who insisted he pick a title from one of the poems in the volume, and thought Some Trees best, a decision about which John was ambivalent.” Ashbery informed Roffman in an interview that he “had included his best experimental poems in the manuscript, but Auden removed any poem that had objectionable language, including ‘White’ (because of ‘masturbation’) and “Lieutenant Primrose” (because of ‘farting’). Ashbery accepted all Auden’s changes, but he privately objected.”

Also, as is well-known, Ashbery wasn’t crazy about the begrudging introduction Auden wrote for Some Trees. Roffman suggests Ashbery’s displeasure may have gotten back to Auden himself, who — she reports for the first time — once told a friend that Ashbery was “‘the most ambitious person’ he had ever known,” which, given Auden’s circle of acquaintances, is saying something…

This is just a glimpse of the many gems of literary gossip and new insights that abound in this biography. As I said in my review, “The Songs We Know Best offers up a feast of new details, documents and colorful anecdotes that will be foundational for any future understanding of Ashbery.”

You can check out my review in the New York Times Book Review here, and for more coverage of the book, see excellent reviews by Mark Ford in the Guardian, Evan Kindley in the New Republic, and Matthew Bevis in Harpers.

Such a handsome man.

Pingback: On Five Years of Locus Solus | Locus Solus: The New York School of Poets