February 6, 2023

Shigeru Ban Is Unimpressed by the Mass-Timber Boom

Sam Lubell: Your book, in my opinion, is a great way to learn about timber architecture, how to employ it and how to be innovative with it. And it’s impressive to see how long you’ve been doing it.

Shigeru Ban: Yes, as you know, it’s now very fashionable to use timber. I’ve been working with timber for many years.

SL: In your introduction you talk about your love of wood, and some of your very specific influences. You talk about a carpenter who worked in your family house, and important architects and engineers like Frei Otto, John Hejduk, and Hermann Blumer. Can you sum up how you became a wood aficionado?

SB: I wanted to be a carpenter when I was small, because I loved the smell of wood, and I thought the process of using it was magical. It was like magic for me that traditional carpenters made houses and fine chairs without any power tools. It’s beautiful just watching that happen. Today that kind of approach is not really possible, but in those days Japanese carpenters didn’t use any electric tools. It was incredible to make a house just from wood.

But I also love wood’s limitations. If you want to make a structure out of steel, it is such a wonderful material. You can do anything you want by welding. You don’t have to create an innovative joint. It’s such a wonderful, easy material. But wood is a natural material, so there are many more challenges. So my interest is in using that kind of humble material and working within those limitations to create something special. To take advantage of the limitations.

That is why for many of my timber structures I don’t want to use a steel joint. Once you start using steel joints it doesn’t need to be a timber structure. It can be a steel structure. You’re just replacing the linear element; it’s not really interesting. My interest is in creating a structure which can be built only with timber. That is characteristic of timber.

I’m always looking for the challenge. Because if I’m given an unlimited budget with a huge site without strict limitations or requirements from a client, I don’t think I can design anything. I always look for some problem or limitation to find the solution.

SL: Environmentalist Paul Hawken, who wrote one of the book’s essays, talks about how your use of wood is celebrating the living world versus the man-made world. Not conquering nature but being part of nature.

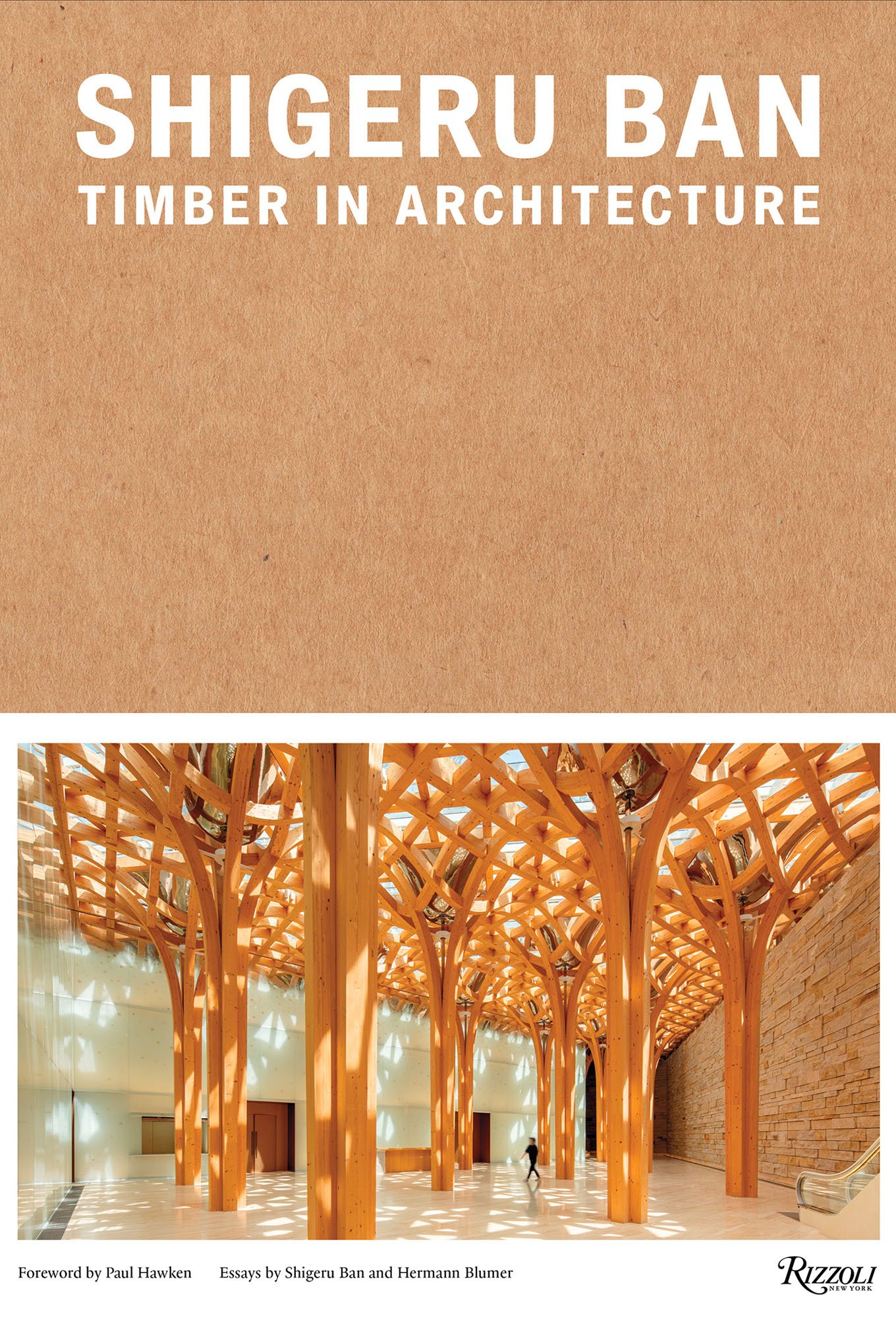

SB: Not exactly. Even I don’t like to be in a woody space surrounded by everything with wood. I like to have a contrast. I like to articulate; I like to emphasize the beauty of the timber by contrasting it with something else. So it’s like having this beautiful stone wall in the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe. The pattern and nature of the stone is so beautiful because of the contrast with a neutral material like white seating and very simple space. So in order to emphasize the beauty of wood, I don’t want to be surrounded by wood.

SL: Mass timber is so popular now. It’s been a remarkable rise. It’s not a new technology, but this kind of widespread use is new. So why do you think it took so long to gain acceptance? Do you think it’s because people had a lot of misconceptions? They thought it was unsafe or cheap or not sustainable? Not practical? Hard to maintain? Why do you think it was?

SB: Architects are always looking for the fashionable style of the day. In the ’80s, Postmodernism was very popular, so people’s interest was not material or structure. It was about the surface or the collection of surfaces. And in a very short period of time, the fashion became Deconstructivism. There’s always a fashionable style of the day in any time. I think people are always looking for the next style to follow. I think because of the big movement toward sustainability, and the ecological movement, timber has now become the most popular material.

SL: But it seems like there’s more to it. The material itself—

SB: No, I think that architects use wood as a decoration now and it’s just very superficially used. My interest is not only in using natural material but in not wasting material, saving energy. This was a philosophy of Frei Otto, one of my mentors. He said that his interest was in having the minimum material or minimum energy to get the maximum space. So that’s the same thing. How to take advantage of each characteristic, or each material or each method of construction to reduce material and energy but still gain space. I’m doing the same thing now with materials like carbon fiber and plastic.

SL: What do you think it is about you that drives you to work with materials and techniques that are not fashionable?

SB: Well, since I was a student, when I studied history of architecture, I was a big fan of Frei Otto and others like him. They could avoid following the fashionable style by inventing their own material and structural systems. So I wanted to be an architect who was not influenced by the fashionable style. I don’t want to copy other people’s designs. I want to make my own structural systems. That’s why I started developing my own systems for paper structures and wood structures.

One example is the roof of the Centre Pompidou in Metz. I wanted to use the timber structure horizontally, not vertically. Normally, in order to take advantage of the structural effect of beams, we have to use them vertically. But I started using them horizontally in order to avoid the complicated connection of steel overlapping with timber. The idea came from a traditional Chinese hat. Originally I worked with Ove Arup, and I proposed my structural design. They proposed a different structural system, saying it was cheaper, and I compromised. But the price turned out to be more than our budget, and the mayor forced me to change the structure to steel. I didn’t want to do that, so I visited a few architects who were really good with timber, and finally I met Hermann Blumer through a timber contractor in Germany. When I showed him my original design, he immediately said that it was possible, and cheaper than the other one. In two weeks he had analyzed it and gotten an estimate from a contractor. I changed my engineer to work with him because he always understands my philosophy and we share the same direction. He’s one of the real genius engineers who can realize my proposals.

SL: Are there people that you’re following, either engineers or architects that are really being inventive with wood?

SB: I don’t see anyone.

SL: Do you think there are a lot of things holding back real inventiveness with wood? Perhaps it’s because the codes haven’t adapted? Or because of cost? Lack of training? Or is it just lack of imagination?

SB: I think timber specialists, with expertise in both engineering and architecture, are very limited. In most schools there’s nobody who can really teach timber structures. There’s nobody like Frei Otto. He not only pioneered the thin membrane structure, but he is also the pioneer of the timber grid structure.

SL: Do you see timber becoming a default in construction? Do you think that it could someday replace concrete and steel?

SB: No, no, no. It cannot replace other materials because each material has its own characteristics. For instance, some people try to make high-rise buildings out of timber instead of steel. I’m not interested in doing that because timber is not appropriate for high-rise building. Timber is so weak, and protecting it from fire is so difficult. Now in Japan some companies have made fire-rated timber structures, but it’s fake. Because of our codes, it’s timber surrounded by cement and just decorated outside with a very thin wood like a timber column or beam. But if we start doing this, the inside could be concrete or steel. It doesn’t matter. High-rise building with this kind of material is not necessary. It’s all fake.

SL: It clearly sounds like you’re not impressed with the majority of the timber architecture or construction that’s happening right now.

SB: The architect has to invent their timber system structure, not depend on the engineer. I never asked Mr. Blumer to design the structure. I always designed it myself, and he analyzed and helped me realize it. But most architects just design the shape and ask the engineer to find the solution in timber or even steel. They don’t design the structure.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Viewpoints

Navigating the Path to Net Zero

METROPOLIS mines its archives for pioneering perspectives and projects that prove the possibilities of net zero design.

Projects

WholeTrees Brings Structural Round Timber to the Children’s Museum of Eau Claire

the Children’s Museum of Eau Claire makes use of a new carbon-smart structural round timber (SRT) by Madison, Wisconsinbased timber products company WholeTrees Structures.

Profiles

Shepley Bulfinch Celebrates Its 150th Anniversary with Boston Exhibition

A Legacy of Design Innovation, on view through May 7, commemorates the firm’s decades long legacy of progressive practice and innovative design.