Symposium, a philosophical work by Plato written between 385 and 370 BC, is about a friendly competition between speeches given by famous men at a banquet. During the talk, Socrates says that a priestess from Mantinea named Diotima taught him “the philosophy of love” when he was young. Socrates also says that Diotima slowed down the spread of the Plague of Athens, which destroyed the ancient Greek city-state of Athens in the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430 BC). Aside from these few details, we don’t know much about Diotima as a person.

Diotima, the woman who originated the concept platonic love

Even with these small pieces of information, Diotima played a big part in the Symposium, even though she didn’t even go to the banquet. She taught Socrates that love is a way to get closer to God and that the goal of love is immortality, which can be achieved by having children or making beautiful things. From this argument, we got the idea of Platonic love, which is a kind of love that is not based on physical pleasure and has been around for thousands of years.

She taught Socrates that love is a way to get closer to God and that the goal of love is immortality, which can be achieved by having children or making beautiful things.

Even though this idea was named after Plato instead of Diotima, there was never any doubt in the ancient world that Diotima existed. A bronze relief from the first century that was found in Pompeii shows Diotima and Socrates, with the figure of Eros in the middle. In this relief, she is in the middle of a lively conversation, and Socrates is listening carefully. Diotima was also talked about as a real person in writings from the second to the fifth centuries AD. But Diotima’s existence was questioned many times over the next few hundred years.

Maresilio Ficino, an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who lived from 1433 to 1499 and was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance, wrote Oratio Septima II (The Seventh Address II) in 1485. This suggested that Diotima was made up. Ficino’s comment that it was silly to think that a woman could be a philosopher took away Diotima’s voice and identity. This turned the priestess into a fictional character, which was her status for the next 500 years.

Real or Symbolic: Is Diotima in the Texts?

Nearly all of the people named in Plato’s dialogues have been found to be real people who lived in ancient Athens. Diotima is the only one whose existence has been questioned, and that’s only since the 15th century.

Early Middle Ages scholars and ancient people who would have known Diotima was real never questioned her existence when they talked about her. Even though Diotima’s ideas are different from Plato’s, she is still praised, which is rare in Plato’s work and shows a real respect. Early writings about Diotima also show that she was respected for her skills and her place in society. For example, Lucian’s comedy The Eunuch, which was written in the second century AD, starts off by mentioning Diotima, Thargelia, and Aspasia as proof that there were women philosophers. There is no reason to think that these women were anything other than philosophers who did their work.

The French scholar Giles Menage’s 1600 book, The History of Women Philosophers (Historia mulierum philosopharum), doesn’t question Diotima’s existence either. Menage says that Plato’s Symposium and Lucian’s words are proof that she exists. In the introduction to her translation of the Menage text, Beatrice Zedler writes, “What Menage wants to show is that there have been plenty of women philosophers, but we don’t know much about them.” “Diotima taught Socrates the philosophy of love,” Menage wrote. “Socrates himself says this in Plato’s Symposium.” In the early sixth century, Lucian used Diotima as an example of wisdom and understanding when he said, “…Diotima shall be copied not only in those qualities for which Socrates praised her, but also in her general intelligence and ability to give advice.” Even though Lucian’s text doesn’t question Diotima’s existence, the translator’s footnote on her says, “Diotima, a priestess of Mantinea, is probably made up because we only hear about her in Plato’s Symposium.”

“…Diotima shall be copied not only in those qualities for which Socrates praised her, but also in her general intelligence and ability to give advice.”

Lucian

Scholars say that this doesn’t mean that Diotima wasn’t based on a real woman. Most scholars in the 1800s and 1900s thought that Plato based Diotima on Aspasia, Pericles’s mistress, because he was impressed by her intelligence and wit. But this theory had another problem: in Plato’s dialogue Menexenus, Aspasia is called by her own name, which shows that Plato would not have made up names. This shows that Diotima is more likely to be a real person than a fictional one. But even though it seems like the idea that Diotima wasn’t real comes from Ficino’s inability to understand the idea of a female philosopher, there are other, more convincing arguments that Diotima did exist.

What does a name mean?

Philosopher Allan Bloom (1930–1992), for example, made it clear that Diotima was not a real person in his commentary on the Symposium. He wrote, “The name Diotima means “honoured by Zeus,” and the mention of the city of Mantinea in the form it appears in here is the same as the word for the science of divining.” She is obviously not real.” This could be an important point. The name Diotima means “Zeus Honor” in English. This could mean that a woman named Diotima honours Zeus or that Zeus honours a woman named Diotima.

People said that Diotima was from the city of Mantinea in the Peloponnese, which sided with Sparta during the Peloponnesian War. This place’s Greek name, Mantinike, seems to come from the root word “mantis,” which means “prophet” or “seer.” Socrates tells his fellow philosophers more important details about Diotima that hint at her successful prophetic powers. So, Diotima Mantinike would roughly mean “Zeus’s honour from the victory of the prophet.” If she did exist, her name and place of birth seem like too much of a perfect match to be her real name and place of birth. Bloom says, “This is one of several places in Plato where Socrates talks about how he stopped being a pre-Socratic philosopher and became the Socrates we know.” Socrates may be a great philosopher, but he didn’t just have this radical philosophical change all of a sudden in the time it took to eat a banquet.

When we put together Diotima’s very short stories and descriptions of her character, we find an intriguing puzzle. Diotima had a strong personality and seemed sure of herself. This was important for the headstrong younger Socrates, or any man in that time when men were in charge, to pay attention, listen, and try to understand her. Socrates, who was a man of reason and science who was interested in inanimate things, didn’t know much about true and deep love that goes beyond the physical. At this point in his life, he might not have even known what the Divine was.

People also said that Diotima was beautiful. But, as we see in the last parts of the Symposium, Socrates wasn’t just interested in beauty on the outside. But since Socrates liked sharp wit and humour, it seems that intellectual capacity is more like the beauty that Socrates was looking for. Also, Socrates would have been very interested in Diotima’s eyes because she was a “seer” or priestess. As a “seer,” Diotima could see things that were beyond the physical or scientific universe. This would have confused and interested the young Socrates.

The Friendship Between Diotima and Socrates

In the conversation with Diotima, Socrates’ lack of experience was brought up in Symposium. However, the conversations with the wise woman from Mantinea were about Socrates’ time in Athens. Socrates probably met Diotima when he was no more than 29 years old, and maybe even younger. Diotima’s purifying action in Athens is also important because, according to what Socrates said in the Symposium, it would have slowed down the spread of the plague in Athens. Since the plague in Athens happened in 430 BC, this means that Socrates probably learned from Diotima around 440 BC. Several times in the text, it says that Socrates and Diotima visited each other often over a long period of time.

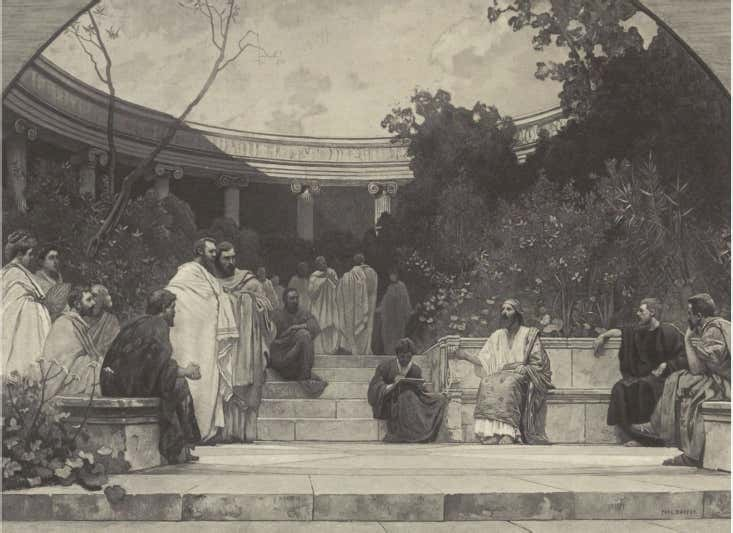

This exchange of knowledge with a woman, who was not a “philosopher” in the way that Socrates or Plato were at the time, gave Socrates the support he needed for a new way of thinking, which allowed him to argue against the poet Agathon’s speech about eros in the name of truth. Socrates brought Diotima, who is a woman, to a group of men only called a symposium. The symposium was a group of men who were at the top of Greek culture, and Diotima would not have been allowed to join it in real life. The fact that she is also a foreigner (without getting into the specific meanings of her being from Mantinea) added to the strangeness of her figure when compared to the refined and conspiratorial harmony between the people at the symposium in Athens.

A priestess and a prophet

Socrates mentioned Diotima as a priestess who had ancient knowledge in his speech. This made the other people there treat her words as riddles and see her as one of the keepers of truths that can’t be put into words. In this way, Diotima’s way of teaching is similar to that of the Delphic oracle, but the symbolic material she gives Socrates to think about before he gets into philosophy is much richer.

When it was Socrates’ turn to speak at the symposium, he said, “I’ll start by saying who and what love is, and then I’ll talk about what it does. I think the best way to do this is to use Diotima’s question-and-answer method.” She used the same arguments against me that I just used against Adathon to show that Love was neither good nor beautiful.

As the conversation goes on, we hear Diotima teaching Socrates about love, including the love of wisdom, virtue, beauty, and the good. In Plato’s works, these are the ideas that are often looked at and talked about. Diotima uses myths and analogies to help her students understand and talk about things. This is how she gets them to come up with ideas. She seems to have had a big impact on Socrates and taught him well, because he is able to remember, interpret, and build on the things he says he learned from her as he encourages, irritates, frustrates, and angers others in the Platonic dialogues.

Some people might say that Socrates wouldn’t ask a woman for advice on philosophical questions, but in two other dialogues, Socrates talks about the wisdom of priestesses. Socrates used the Priestess of Delphi as part of his defence in Plato’s Apology. The Priestess of Delphi was a prophetess who said Socrates was the smartest man in Athens. Based on these texts, we can assume that Socrates didn’t mind talking to priestesses and even trusted what they told him. So, it didn’t seem strange that he might have talked to Diotima, a priestess from Mantinea.

In another text, Socrates talks about another woman who taught him things. Socrates spoke well of the woman who taught him rhetoric, Aspasia, in Menexenus. Socrates says, “I shouldn’t be surprised that I can talk, Menexenus, since I have a great teacher in the art of rhetoric, she who has made so many good speakers.” The woman, whose name is Aspasia, was never called into question.

2 Replies to “Diotima and the Philosophy of Love”