Old Retro!

Shooters!

Maze Games!

Single-screen Platformers!

Platformers!

Antz

Platform: Game Boy Color

"Z," the movie's memorable protagonist voiced by actor Woody Allen, could be any old ant here.

Although no longer given much regard, the Dreamworks-led Antz was a much-hyped property in 1998. Fully rendered in, at the time, state-of-the-art CGI, the studio promoted the film as the future of animation while hoping, more privately, to blunt the always encroaching Disney machine. This meant a blitz of books, toys—and yes, video games!—to accompany the movie’s release.

Hence this, a mediocre retread of the movie’s main beats, distilled to ugly, 8-bit form. It’s a platformer of the typical licensed variety—functional but not particularly interesting—with the player bounding the protagonist Z around levels that play almost like reskinned duplicates of each other. Remember the funny nightclub scene from the film? It’s recreated here as a bunch of tunnels and shafts great for (inexplicably) collecting rings and hopping about. Remember the epic termite battle? It’s recreated here as a bunch of tunnels and shafts great for (again) collecting rings and hopping about. Once the proceedings reach outside the hive, a scant more variety is introduced, but by then it’s already too little, too late.

The 8-bit minimalism does it no favors, either, featuring well-animated but not particularly endearing takes on the title characters. Music is shrill and droningly repetitive, evoking none of the movie’s ambiance or charm. In fact, it’s only the game’s interstitial cutscenes that suggest any connection to the source material—these are usually well drawn and provide a gist of what the film is actually about.

Not good, but playable—fans might want a copy to complete their shrine of everything Antz, but otherwise, this is another license-based game rightfully snubbed.--D

Publisher: Infogrames

Developer: Planet Interactive

Release: Sept. 24, 1999

Genre: Platformer

Axelay

Platform: Super Nintendo

The Illis System has succumbed to an alien invasion, its fleet defeated save for one stubborn survivor—the righteous pilot of the powerful Axelay “stratafighter.” He must now go where no man has, penetrating the heart of the enemy armada to eliminate its mysterious leader. Hostile cityscapes, an aquatic underworld, even a lava planet alive with giant, airborne worms—the game’s six worlds are as diverse as they are lethal, packed with every imaginable danger. More noteworthy, however, is the dynamic perspective, which alternates between vertical and horizontal action to produce a shooter of unusually eclectic feel. The overhead levels are particularly immersive, tilting the view to simulate a perpetual horizon from which objects gracefully “fall” into being. The side-scrolling missions are less mesmerizing, benefitting instead from stronger level design and more straightforward confrontations. Indeed, the vertical stages’ dipped viewpoint leads to some cramped navigation and nebulous hit detection rarely felt in their left-to-right counterparts. The game’s selectable weapon system is similarly unique, allowing the ship’s pod, side, and bay compartments to be affixed with crucial add-ons. Initially, these armaments are rather bland—the “Straight Laser” fires a fireball-like volley, the “Round Vulcan” spreads bullets in a two-way spray, and the “Macro Missile” launches dual torpedoes at incoming foes. But newer weapons become available over time, and some, such as the all-penetrating “Wind Laser,” prove almost cathartic in their destructive fun. And yet, this idea of withholding arms seems a strange misstep, as it renders certain weapons unavailable, and thus wasted, for large swaths of the game. Fortunately, the game is more gracious in terms of challenge; sustaining damage merely causes the loss of the currently selected weapon. This equates to having a four-hit life bar, provided players switch to the next gun before being struck again. Instant respawns, extra lives, multiple difficulties, and added continues also keep the proceedings fair. Well-crafted graphics and a bold soundtrack elevate the action even further, but there’s no shaking the grounded truth—while half the game is stellar, the overhead sections fall just short of the stars.

Final Thoughts: Axelay is often deemed as being one of the SNES’s finest shooters. And with its massive bosses, slick use of Mode 7 effects, and surprising lack of slowdown, perhaps it deserves that distinction. And yet, when counterbalanced with its uneven level design, underwhelming animation, and nominal replayability, a newcomer might just second-guess that glowing praise. But no matter; Axelay remains a safe, reliable choice for any shooter fan stuck with only a Super Nintendo.--D

Publisher: Konami, Inc.

Developer: Konami Co., Ltd.

Release: September 1992

Genre: Shooter

The overhead levels show more spectacle and feel more epic, but the horizontally-scrolling stages play better overall.

The bosses, as in many a shooter, offer some of the most memorable moments.

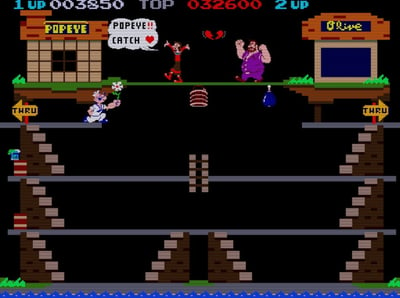

Bomb Jack

Platform: Arcade

Like many early-‘80s arcade games, Bomb Jack is inexplicable in its premise. As a superhero (named Jack?), the player must launch himself around the screen, collecting (and presumably defusing) as many bombs as possible in a single bound. As he does so, enemies spawn and zip around after him, anxious to cancel his flight.

They will succeed.

This is due to “Jack,” despite his ‘super’ distinction, being a rather fragile hero. One hit from anything ends his pint-sized life, and he’s defenseless otherwise. All he can do is swerve through the air, slow his descent, or drop immediately back to a platform, all while maneuvering through swarms of flying saucers, golems that transform into ricocheting death orbs, and other nonsense. Fortunately, collecting bombs feeds a meter that, once full, releases a ‘P’ icon that flings itself around the arena. Snatching this “power-pellet” turns the enemies into defenseless, point-granting coins, affording the player a brief reprieve from the insanity.

The game is fun, but just briefly; the repetitive nature of the (often frustrating) gameplay becomes obvious after just a few stages—and since there’s a hundred of these deathtraps to suffer, most players will eventually curse and move on. An improved sequel—Mighty Bomb Jack—is the version worth trying today, with the NES iteration currently available on the Nintendo Switch on-line service.

But…is Bomb Jack a true single-screen platformer? He definitely jumps! There are platforms! The levels are contained in a single screen! That said, the game can also be likened to paddle/ball games like Breakout and Arkanoid in which a sphere must be propelled into stacks of blocks, “collecting” them, in a sense. Bomb Jack simply makes its hero both the paddle and the ball. Or rather, the game can be categorized with maze-games such as Pac-Man thanks to its “grab-the-bauble” and “dodge-the-monster” proceedings.

But assuming it’s indeed an SSP, and despite its own underwhelming nature, Bomb Jack at least reveals the versatility of the genre. Give it a try, then seek the sequel.--D

Publisher: Tehkan

Developer: Tehkan

Release: October 1994

Genre: Single-screen Platformer (sort of)

Filling the meter (with the x1 sitting inside) releases the 'P' icon seen at the bottom right corner of the first image. This turns all the baddies into coins for a few fleeting seconds (as seen in he second pic).

The backdrops are few and repeat without much continuity. Here, players can see the Tehkan (developer's) headquarters.

BurgerTime

Platform: Arcade

BurgerTime seems born of a former fast-food worker’s fever dream, one in which the condiments he once prepared have come to life…and want a piece of him instead. And considering the game’s developer, Akira Okimoto, had previously worked as a fry cook, this unseemly feeling isn’t altogether misplaced.

So, players control the harried Peter Pepper, a quick-order cook who must scurry across a series of catwalks/rafters, toppling slabs of meat and toppings down chutes to create platters of mega-burgers. Impeding his efforts are a slew of ever-encroaching enemies; Mr. Hot Dog, Mr. Pickle, and Mr. Egg all want poor Peter dead.

And, no doubt, these fiends have the advantage. Peter moves slowly, even stodgily, over the floors and up the ladders. And worse, he’s nearly defenseless, armed with only a few rattles of a pepper shaker (pepper spray?) that temporarily stuns the incoming monsters. He can also flatten the baddies by tumbling foodstuffs upon them, but even when successful, the mutant edibles always return. In classic fashion, Peter’s nightmare is perpetual—after completing six stages of increasingly taxing design, the cycle repeats, dooming Peter to an endless shift in which he might just become the secret meat.

Much like fast food in general, BurgerTime is tasty at first, but soon becomes cold, then gross, as players begin to notice the slow gameplay, stiff controls, and obnoxious, looping music. Better single-screen games certainly define the era and genre, but the question remains—does BurgerTime qualify as true single-screen platformer? Without an ability to jump (or even fall), probably not…but because its 1990 sequel, Super BurgerTime, does introduce true platforming along with a number of other mechanics, the original—the prototypal entry, one could argue—is tentatively granted the same classification.

Which is to say, despite its heritage, BurgerTime is a remarkably average, flavorless game.--D

Publisher: Bally Midway

Developer: Data East

Release: November 1982

Genre: Single-screen Platformer (kinda?)

There's not much story, but the game does a decent job explaining the basic goals and introducing the "cast."

Getting trapped is all too easy. Fortunately, the player can "pepper spray" his foes to escape, if only for a set number of times.

Crush Roller

Platform: Neo Geo Pocket Color

The screen above will become increasingly common in the later stages.

The "Pac-Man Clone." It’s the informal term for any overhead maze game in which collecting and survival are the foremost priorities. In Pac-Man, this meant eating all the dots while avoiding the ghosts. In Ladybug, this meant eating all the flowers while avoiding the insects. In Mouse Trap, this meant collecting all the cheese while avoiding the cats.

But Crush Roller tries something different—rather than skittering a critter through a maze of crumbs and foodstuffs, the player here steers a nondescript paintbrush. There’s no food to collect, just corridors to paint. And once the maze is completely glazed, another set becomes available. Enemy “fish” provide the challenge, patrolling the arenas and often giving chase. Players can escape the stalkers by using “rollers” situated in specific lanes. Almost like a zipline, these squeegees race back and forth, flattening foes and buying precious time, but at a cost; the fish always respawn now faster than before.

Based on the 1981 arcade game (called Make Trax in North America), this port is easily the definitive edition. Vastly improved audio and aesthetics aside, the game offers a variety of new mazes that become selectable as progress is made, allowing players to essentially plot their own unique “route” to the conclusion. Moreover, a unique “saboteur” will appear in each level, leaving footprints across the freshly laid paint and undoing progress. Should these characters be intercepted, however, they become added as a memento to the visual “Ojama-Collection” archive, giving expert players a curious sub-objective to achieve.

All this whimsy, however, belies a cruel difficulty; in later levels, enemies become especially swift-finned, making escape nigh-impossible unless a roller is nearby. Also odd, rounding corners sometimes leaves single pixels behind unpainted...and virtually invisible. Having to pinpoint and then backtrack to these off-color artifacts can be nerve-wracking, especially on a small screen already crowded by ever-encroaching foes. Infinite continues help mollify the frustrations somewhat, but high-score chasers are in for a chore.

Still, this is an excellent update to the original game, with enough nuance and charm to elevate it well above being just another insipid clone. It’s not Pac-Man…but it still paints a pretty picture.

Publisher: SNK Corporation of America

Developer: ADK Corporation

Release: 1999

Genre: Arcade, Maze-Runner

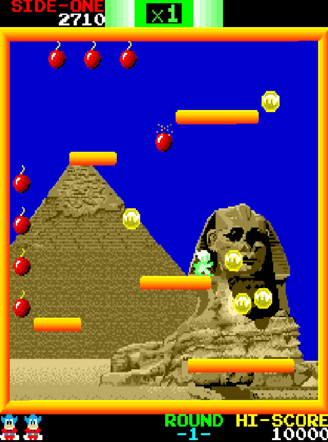

Diet Go Go

Platform: Arcade

The two athletes - not pumped up, but plumped up. Ha!

As a follow-up to Tumble Pop, Diet Go Go would be almost akin to a bootleg reskin if not for one key difference—while the former was about exploiting gravity to one’s benefit, Diet Go Go outright defies it. This time, players must send their attackers airborne, bouncing them like beach balls between other foes. But rather than using a vacuum set in reverse, the male and female pair toss fruit (pink apples?) to fatten their baddies up. One piece suffices, bloating the minion enough to be knocked into other foes, while a second fruit “poufs” them into balloon-like wrecking balls that can be sent ricocheting around the screen, pulverizing anything in its trajectory. It’s fun if nonsensical. And requires little, if any, real skill or finesse.

And that, alongside its derivative nature, is Go Go’s greatest flaw. Levels almost seem to complete themselves, with a single ping-ponging attack often clearing a drove of enemies with little thought or action by the player. Powerups, from speed boosts to increased firepower, make progression even easier. The only real wrinkle is the addition of a slot machine—by collecting coins, three roulettes will spin at the top of the screen, sometimes rewarding players with a deluge of gems and other items. But effectively, it adds little to the overall experience.

More interesting, maybe, is the game’s obsession with food. Although the protagonists can hurl an unlimited, rapid-fire supply of fruit, enemies can fling their own foodstuffs. Touching a cupcake belched by, well, a walking cake, will bloat the player and decrease his speed, while a second hit brings complete obesity…and defeat. It’s a quirky, even counterintuitive dynamic, considering food almost universally signifies a point bonus in similar games. And instead of having to run that extra poundage off, which would have made too much sense, all it takes is grabbing another item—an energy drink—to trim that poundage off.

Like Tumble Pop, players complete stages by globetrotting the world. But unlike its predecessor, the locales here are much more surreal and bear little resemblance to their real-world counterparts. England, for instance, is set in a bizarre candy land, Russia holds a haunted grove, and the Bermuda Triangle features, what else, an underwater Atlantean city. Bosses are entertaining but equally bizarre, ranging from a gigantic vampire to a crab-like, walking pot of boiling carrot stew. Dr. DePlayne, the villain and only true holdover from Pop, delivers the final confrontation.

Where Go Go excels, at least marginally, is in its art design. Enemies are more expressive, backgrounds more detailed, and the main characters (slightly) more memorable than in Tumble’s efforts. The music, unfortunately, merely serves its purpose, lacking the catchy quality of its forebear’s; while Tumble Pop manages to remix its main theme again and again without anyone minding or even noticing, Go Go’s attempt to do the same is more glaring in light of already feeling a bit recycled. And yet, despite its insipidness, the game is still fun. Fast-paced and polished. And extremely accessible to the casual passerby.

But without some greater substance—some added technique or flourishes to learn—the game becomes the junk food it’s supposed to hate. A middling recipe destined for the kitchen drawer. An ephemeral distraction at best, a disposable diversion at worst.

Diet Go Go never received a home release, and the “why” is obvious. The game is just a snack; a 25-cent palate cleanser between bigger, zestier dishes.--D

Publisher: Data East

Developer: Data East

Release: 1992

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Bosses are pretty wacky, with the top parodying the Evil Queen from Disney's Snow White.

Wordless "cutscenes" are interspersed between the completed worlds. Funny!

Don Doko Don

Platform: Arcade

Meet Bob and Jim, the game's two unlikely heroes.

Taito released a flurry of platformers in the late ‘80s, many of which were of the single-screen variety. Bubble Bobble, of course, is the most renowned, and led to a series of popular sequels and spinoffs. But a separate franchise started around the same time, starring not bubble-blowing dinos, but a spunky witch who transformed her enemies into mushy cakes. It never received a true sequel, but did inspire a similar title set (vaguely) in the same universe. Known by its Japanese-transliterated name as Don Doko Don, the witch has been transplanted by two dwarven, mallet-wielding lumberjacks tasked with rescuing the land’s precious princess.

As unlikely as they seem, these garden gnome doughboys are actually a natural fit for a world of runaway mushrooms, lollipop-lapping crocs, penguins donning cat pajamas, and giant worms anxious to swallow the gnomes whole. Players must guide their wizened warriors through fifty-stages of such wackiness, stunning enemies with their mallets and then flinging them at other foes. Multiple baddies can be carried for a stronger attack, but like a hot potato, these fiends can't be held for long—tossing them fast is critical to survival.

But no matter. The stages themselves are the bigger threat, featuring platforms and ledges of often lethal character. Some are bouncier than an air mattress, constantly bobbing the player in errant directions. Others are slippery, or act like conveyors, or literally spin around, knocking minions in wayward motions; no matter the type, they’re always arranged around dangerous, ever-encroaching foes. Couple these quirks with level designs that don’t always offer an obvious or intuitive solution, and the game can get surprisingly difficult.

The dwarves aren’t particularly formidable, either. They move as one would expect from a rotund old-timer—sloooow, in other words, and their mallets are barely better, offering both limited range and power. As in other Taito platformers, powerups are always spawning, including crucial strength potions that allow enemies to be hurled through walls (to hit other oblivious foes), and speed boosts to help prod the stodgy gnomes along. These enhancements last until defeat, but other consumables, from time-stopping statues to throwable hammers, are strictly temporary. Some items are so uncommon that, in typical Taito tradition, their true purpose is often lost on the casual player. Indeed, an additional fifty levels (and a secret ending) hides within Doko's depths…but most will never know.

A highlight, perhaps, are the game’s bosses that dominate every tenth stage. Although designed to steal lives (and quarters), they’re at least memorable, featuring a variety of outlandish designs. Similarly, the enemies are colorful and brim with personality, granting a comical touch to the proceedings. In fact, it’s only the heroes who disappoint, the pair feeling bland, even generic, by comparison. Backgrounds, although generally flat and low-detail, at least change by stage, veering radically from each other depending on the setting. Some jaunty tunes further establish the quirky mood.

Which means Don Doko Don is a good game, and one that probably deserves more prominence in the grand canon of single-screen releases. It isn’t as instantly fun as Snow Bros., lacks the lullabic warmth of Rod-Land, and can't match the infectious catchiness of Bubble Bobble’s main theme in terms of sound. But as a successor to The Fairyland Story, this is an admirable step forward.

If only Taito had given the series another chance.--D

Publisher: Taito

Developer: Taito

Release: 1989

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Later levels take an especially surreal edge, with twirling platforms and psychedelic backgrounds.

Bosses can also be...a bit flamboyant.

Fans of The Fairyland Story may remember this ravenous worm. Come on, now, where're Ptolemy and her tasty cakes?

Donkey Kong Jr.

Platform: Arcade

The game is tough. The surreal Stage 4 is especially so.

The original Donkey Kong is a legitimate classic—if Pac-Man gave the medium a persona, DK gave it a sense of consequence, an added incentive to prevail. With these two titles, gaming overcame its racing and space-blasting constraints to become a journey not just of action, but of synergy shared between player and avatar. Unlike its contemporaries, DK offered a conclusion—a possible happy ending—if the player was willing to get serious. Movies and books offer effort-free finales, but in gaming, Kong signified a new paradigm: nothing is guaranteed. Happy endings needed to be earned.

Or put another way, Donkey Kong elevated the characters and quest above the gimmicks. Both hero and villain had their separate roles and goals to play. And anyone who participated in their unfolding drama—the player—became part of the story by joining, or even becoming, the protagonist himself. For some, it was an out-of-body experience.

Then Donkey Kong Jr. came around, demoting the original’s hero to villain status and inviting players to now command Junior, the big ape’s pudgy son. Like Mario in the previous outing, the wee primate must traverse four stages of assorted hazards, this time climbing vines and dodging chomping traps and hurdling pesky birds to free his dad from captivity. It’s another “reach the top” affair, but the graphics are more expressive and Junior’s moveset a bit more elaborate than what the first game dared to achieve. Superficially, it’s the superior experience. But somehow, it fails to captivate—to fully absorb—as its predecessor did just a year before.

Why? Some might say it’s due to Junior’s stodgy controls, whether jumping from platforms or hoisting himself from vine to vine. Others might blame the unrelenting enemies that are difficult to evade or even predict.

But perhaps the true reason owes to a deeper, more primal source. If the original Donkey Kong encapsulates, however imperfectly, the Hero’s Journey, it’s therefore a link to the collective unconsciousness of Man—his need to protect, to rescue, to be heroic. This makes Mario the player’s insertion point, the individual each must become to rescue his princess of myth. But in Junior’s case, such a spiritual leap isn’t so easy. Who dreams of freeing a goofy gorilla, especially one hated and defeated in the previous adventure?

That’d be like the knight, after saving his damsel, rushing back to now help the dragon. It’s a little weird and inexplicable. And likely explains why Junior’s game, even today, is nowhere near as adored as its forefather. And indicates why Junior himself has all but been stricken from the Nintendo canon.

People long to be heroic—to be dashing men, in a sense.

But who dreams of being the beast?—D

Publisher: Nintendo

Developer: Nintendo R&D1, Iwasaki Electronics

Release: 1982

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Mario is the villain? And is the second "Mario" a prototypical Luigi?

Oh, Mario also has a secret hideout, apparently. And a helicopter. Good thing Junior has Pauline's parasol with which to give chase!

Although Junior is featured prominently, Nintendo has abandoned the poor tyke in recent years.

Galaga: Destination Earth

Platform: Game Boy Color

The backgrounds suffice...if nothing else.

Hasbro wasn’t always just a toy company; in the mid-90s, it founded Hasbro Interactive, a video game production house dedicated, in part, to reviving old-school classics from gaming’s past. Yes, even back in the year 2000, games like Frogger and Pac-Man were already considered retro.

Unfortunately, Hasbro Interactive’s take on these faded franchises didn’t always achieve the same classic status. A prime example is the company’s 8-bit take on Galaga, a sloppy “reimagining” that zaps all the fun and charm from the original. Enemies swarm and swerve in indecipherable patterns, pelting the poor player’s ship with bullets difficult to dodge and, nay, even see! Indeed, the screen now scrolls left and right, allowing the aliens to drop their payload outside the screen at inexplicable, death-ensuring trajectories. The audio is also lacking, deprived of the original’s whimsical pops and pipings, although graphically, some of the backgrounds do sport a sort of pixelly, 8-bit charm.

So…don’t bother. Stick with the original or its legions of follow-ups and better remakes. Galaga ’88, Galaga Arrangement, and Galaga Wars for starters…--D

Publisher: Majesco Entertainment

Developer: Pipe Dream Interactive

Release: Sept. 25, 2000

Genre: Arcade Shooter

Mario Clash

Platform: Virtual Boy

In Mario Clash, frontal attacks are useless on most foes, good for turning them around and little more.

As seen in the bottom-left corner, defeating enemies requires a sly attack from the side, meaning players will always be seeking the opposite plane.

Although Mario himself is almost invisible in this shot, he's managed a 2X combo by ricocheting a shell between two enemies. Such maneuvers are tough to pull off but are immensely satisfying.

Uh oh! Mario's in a predicament here, having no shell and surrounded by baddies. Without a Koopa Troopa nearby, the plumber can do nothing but evade and pray...he's utterly defenseless.

An occasional bonus level punctuates the action in which Mario must leap for the coins passing overhead. If played without the depth of the actual VB headset, catching all twenty is especially tricky.

Nintendo’s ill-fated but perhaps (slightly) underrated Virtual Boy was not meant for long-winded experiences. Its garish red-on-black graphics were often an eye-straining eyesore that demanded regular breaks. Indeed, the system itself boasted an “automatic pause” feature for this very reason; after so many minutes, the console would suggest taking a rest, allowing the player to pull his head out from the visor and give thanks for a world of color.

Hence Mario Clash, a game made for such fleeting, arcade-style proceedings. There’ no epic quest here to save the Princess or liberate the Mushroom Kingdom. There’s barely a story at all. It’s just Mario climbing, floor by floor, a Babel-high tower that’s been invaded, apparently, by some air-pirate interlopers. Crabs, snakes, beetles, Pokeys, Para-Goombas…the foes are more pest than pirate, making Mario more exterminator than liberator. It’s an obvious nod, of course, to the original Mario Bros., a single-screen platformer in which the hero had a critter-ridden sewer to clear; by defeating every enemy, Mario would advance to the next stage in which another set of creatures had to be expunged.

Mario Clash is no different, forcing Mario to stun, then bump, every enemy he encounters from the current floor. The “how,” however, is where the mission gets tricky—his signature “stomp” move is next to useless in this reality. It’s only good for paralyzing turtles, whose shell he must then hurl at other pests. But just tossing the projectile directly at them is not what the game wants; most enemies must be nailed from the side. This means Mario must travel between the foreground and the background, hurling the shell just as the enemy passes on the opposite, parallel platform.

When emulated on a modern system, this hopskotching between catwalks is handicapped by an acute lack of depth perception. Background ledges often blend with those on the forefront, causing just enough momentary confusion to beg an untimely death. This is how the real Virtual Boy proves itself, the machine providing the necessary sense of depth and clarity to better survive Clash’s dangers. Ideally, skilled players should be able to dive down pipes and warp swiftly between opposite planes, felling enemies with shells and even coordinating combos attacks before making a confident escape. That sensory depth is not only useful, it sets the game's rhythm.

But no matter how it’s played, the action soon grows repetitive long before the final 99th floor is reached, a reality exacerbated by floaty controls and a Mario left helpless unless another shell can be procured. Worse, because everything is fixed to a subtle three-point perspective, targeting is never wholly intuitive. For instance, when Mario is standing at the mid-point of the screen, he’ll toss the shell in a “straight” line as expected. But once he shifts more to the left or right, that straight trajectory becomes increasingly “diagonal” in terms of human perception, forcing players to adapt accordingly as they aim from the back or front platforms. Given how chaotic later levels become, and scarce the shells sometimes are, this slight disorientation can easily lead to swift defeat. And without a save feature of any kind (unless through emulation!), death means a cruel reboot to level 40, the highest floor players can choose when trying again.

Most Mario games are remembered fondly; Mario Clash isn’t remembered at all, its legacy not bad…just nonexistent. The game’s few fans had once hoped, even expected, it would be revived on the 3DS, but that opportunity has long since faded. This leaves Clash in a sort of perpetual purgatory, ignored by its Nintendo jailers who, in truth, seem equally eager to pretend the Virtual Boy itself never existed. If the 3DS was the VB’s spiritual successor, Clash still awaits a similar rebirth.

At least, if it’s a comfort, the game isn’t abundantly good, a quirky artifact of a very specific, transitional period of gaming history. In other words, that early 32-bit era is rife with quality titles sadly unsung in the modern clime, Nintendo-made or otherwise. And Mario Clash is hardly the most deserving of a resurgence.

Maybe, just maybe, not every Mario game is meant for immortality.--D

Publisher: Nintendo

Developer: Nintendo

Release: October 1995

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Mr. Do!

Platform: Game Boy

Note the skilled, assorted "texturing" with the levels above. Without the crutch of color, the artist(s) had to be extra clever in differentiating the game's distinctive stages.

Although an essentially defunct franchise now, Mr. Do! enjoyed a respectable measure of success during the Golden Age of Arcades and the immediate years thereafter. This meant a bevy of ports sprinkled across a number of home systems, some better than others. And the Game Boy version, amazingly, is one of the superior efforts.

So the gameplay is essentially the same—the eponymous Mr. Do, a clown who apparently enjoys digging into the lairs of underground monsters, must either collect all the cherries buried within a stage or, if necessary, defeat all the bad guys. Alternatively, levels can be completed by collecting the rarely-seen diamond, or by spelling “EXTRA” through the metagame of targeting certain creatures. New players will just scramble for the cherries or pop the incoming monsters as circumstances dictate.

No matter the goal, survival isn't easy. Mr. Do attacks with a “power ball” that ricochets around a level, maybe hitting the intended enemy, maybe not. But even if it does, the clown must wait a few seconds before he can attack again, leaving him incredibly vulnerable. A second means of defense—digging beneath apples and dropping them onto foes—can be used for both survival and scoring big points, but the swift-swarming enemies can make setting up a proper trap difficult to achieve.

This Game Boy conversion keeps the original’s frenetic whimsy intact, with well-drawn graphics, invigorating tunes, and some reasonably fast, smooth-scrolling action. This “scrolling” aspect, however, is also the port’s primary (if inevitable) weakness, as the detailed graphics all but necessitate the zoomed-in view. This means only a portion of the playfield is visible at a given time, making the anticipation of enemies exceedingly difficult. (Incidentally, selecting “pause” does reveal the full map and enemy placement). Purists might also disagree with the updated art design that reimagines the monsters as blobby, hairball-like things, and a garish, redrawn clown that looks almost like a monster himself. And lastly, the game’s underlying grid-based structure offers less freedom of movement than, say, the SNES adaptation.

And yet, the serious effort that went into this edition is evident throughout, from the impressive animation to even the menu options; the game is not arcade perfect, but for anyone wanting a quick Mr. Do! fix circa 1991, this was (and is) a sweet cherry jubilee.--D

Publisher: Ocean of America, Inc.

Developer: Universal Co., LTD.

Release: November 1992

Genre: Arcade, Maze Action

Mr. Do!

Platform: Super NES

Original Mode

Battle Mode

The Golden Age of Gaming was a surreal, trippy time for the fledgling medium. From scampering mice and bouncing kangaroos to scattering, neon centipedes, early game design happily embraced the absurd—a style not unlike the earliest cartoons that also indulged in the wacky and weird. But one such arcade classic, Mr. Do!, remains overlooked in this vast milieu; the game still awaits a proper 21st century revival despite its many Pac-Man and Q*bert contemporaries already receiving their generous share. In fact, so overdue is Mr. Do! for a proper return, the last remake it did receive was this very SNES port from 1996!

So, Mr. Do! is about a clown—a clown who inexplicably loves burrowing through the ground and collecting cherries while being chased by gangs of so-called “creeps,” odd monsters who apparently really hate little men in face paint. (Or, perhaps, intruders digging tunnels through their homes?) But unlike similar games like Dig Dug, where the goal is to simply eradicate all the bad guys, the player here has four potential options: grab all the cherries, defeat all the creeps, spell “EXTRA” by defeating specific enemies, or, if super lucky, snag a rarely-seen diamond.

The game’s genius rests in the first two of these objectives. As in Pac-Man, players can scramble for the cherries, hoping to outrun the creeps before becoming overtaken. Doing this, however, often forces the player into taking the second option as more and more enemies emerge from the center of the screen. Indeed, defeating foes often becomes inevitable, even desirable, when just trying to survive and clear the stage as expediently as possible. Mr. Do isn’t much of a warrior, either, so the mere act of attacking presents a strange risk/reward dilemma. His primary defense is a “power ball” that bounces somewhat erratically through the tunnels, maybe hitting the intended target, maybe not. But until it does hit something (and even a few seconds thereafter), the clown can’t attack again. This relegates him to fleeing and, if his timing’s right, crushing his pursuers beneath buried apples. But there are only so many apples….and they can flatten Mr. Do, too…and the enemies can also use them. Thus, what seems a silly Dig Dug rip-off is revealed to be a much more tactical affair of knowing when to pivot between sensible aggression and wise retreat.

Adding to the frenzy is the main sub-objective—every stage has a bonus item that freezes the usual enemies while a hoard of new creatures, the “alphamonsters,” now descend from the top of the screen. One of these creatures is labelled with a specific letter which, if defeated, adds to the spelling of “EXTRA.” Nail all five, and a hard-won extra life is rewarded.

This version is a nice conversion, offering a relatively authentic arcade experience while also including an additional “Battle Mode” that features updated graphics, extra items, and simultaneous two-player action. It’s unfortunate these (mildly) improved visuals and features can’t be activated for the main game, but the mode’s inclusion is still appreciated. More irksome are the controls which cannot perfectly duplicate a joystick’s precision, leading to the occasional, undeserved death.

Mr. Do! remains an oddly forgotten classic that, until someone revives the franchise for modern times, remains best played in the arcade or, amazingly, on the also very-vintage Super Nintendo.

An enthusiastic, if bittersweet, recommendation.--D

Publisher: Black Pearl Software

Developer: C-Lab

Release: Dec. 15, 1996

Genre: Arcade, Maze Action

Nightmare in the Dark

Platform: Neo Geo MVS (Arcade)

Pack foes into fireballs and, um, roll them down slopes. Makes perfect sense!

Since 1986, the single-screen platformer has heavily borrowed from the Bubble Bobble template. Rather than just trying to reach the top, players were now supposed to run their avatar all over the board, collecting items and powerups while trouncing all the baddies. Once the last one was vanquished, a new stage dropped with similar but remixed proceedings.

But more than Bubble Bobble, it was 1990’s Snow Bros. that really seemed to inspire the genre. The elegant mechanic of bowling enemies down slopes into other foes was too obvious, too intuitively satisfying, for other single-screen adventures to ignore. Hence Nightmare in the Dark, a game that, despite appearing a decade later, still shamelessly sticks to the classic’s gameplay.

This time, the player commands a gravekeeper who slings reams of fire at his undead foes. But rather than incineration, the foes merely become paralyzed, allowing the player to continue “stacking” more attacks until the enemy balloons into a full-blown fireball. Now it can be grabbed, dragged, and eventually rolled into other creatures, earning point multipliers for every additional enemy flattened. In short, it plays just like Snow Bros.

Even the powerups are similar, with felled monsters dropping potions for increased speed, longer range projectiles, and stronger attacks. Taking damage removes these buffs, as does grabbing the occasional skull which serves as a sort of anti-enhancement. A mere three hits sends the gravekeeper to his, well, grave, although the game’s arcade-origins means he’s only a quick continue away from resurrection.

Where Nightmare does differentiate itself, however, is in its wonderfully stylized, ghoulish graphics and cool, jazzy soundtrack. Despite all reasoning, the disparate forms gel perfectly together, creating a memorable experience that somehow redeems the derivative mechanics. The five bosses that cap the game’s 25-stage gamut are also a highlight, featuring captivating designs and certain artistic flourishes that far outclass the normal minions. These encounters can also be brutally difficult, absorbing untold quarters from those not playing from an emulator.

In fact, Nightmare’s greatest flaw is not the plagiarism but the unfairness—the hero is simply too slow, his attacks too tepid, to reliably juggle the barrage of enemies and projectiles always swarming from all corners. Forget maximizing points; players will be hard-pressed to merely survive unless they speed through each gamut fast…strategic planning be damned. It’s a problem Snow Bros. also shares, but it’s more a nightmare here.

This is a fun game. A polished game. A game that oozes personality on an almost Tim Burton-scale. Had the same enthusiasm been applied to its underlying fundamentals, this could have stood as an off-kilter, underappreciated classic. Instead, it’s more a reanimated corpse of what’s come before, albeit a strangely attractive one.

And that, of course, might have well been the intention.--D

The art is one of the game's undeniable triumphs, with ebullient bosses and some striking, ghostly backgrounds.

Publisher: SNK

Developer: AM Factory

Release: Jan. 27, 2000

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Saboten Bombers

Platform: Arcade

The single-screen platformer, a genre inherently constrained by its own spatial inhibitions, often relied on bizarre themes and premises to compensate. Whether chasing gorillas up girders or turning pigs into cakes or whapping mushrooms with mallets, it was a style of game often defined by the weird. And Saboten Bombers is the perfect example.

So, the story, or at least the barest suggestion of one, unfolds in a quick scene showing critters—insects and weird plant-like things—apparently overrunning a house. On a window sill, two tiny cacti stand watch before uprooting themselves and hobbling after the interlopers. What then transpires is a 100-stage battle for the home, the cacti traveling from room to room and bombing the pests out of existence.

Yes, the two cacti attack by lobbing bombs at their foes. These bombs will bounce and ricochet around, attaching themselves to any enemy in their path before finally exploding. The more enemies snagged and popped in a single toss brings, naturally, a greater score. It’s not unlike the typical Snow Bros. “bowl them over” dynamic, except here the bomb is as deadly to the player as it is to the creatures. Indeed, the bombs are such a liability, what with their swift, unpredictable trajectories and considerable explosions, they could be deemed the game’s most dangerous enemy.

Not that the usual bad guys are pushovers. Well, some are—Saboten’s foes are unique to other games in that they’re harmless when not attacking. This means the game’s initial critter, a weak starfish-like thing, can be literally pushed around the screen with little retaliation. Moreover, an artful stomp can bring most baddies to a stop, allowing players to corral multiple creeps for an explosive payoff. It’s a subtle collection of mechanics that soon becomes forgotten in an ever-mounting din of incinerations and increasing difficulty. Before long, enemies start respawning in waves, begin taking multiple hits to defeat, and get progressively aggressive with their own explosives, searing the screen in disorienting napalm. All this set against a punishing time limit...even survival becomes a hardship. Those aiming for some fancy high score chains are in for a struggle.

Interspersed between the domestic destruction are competitive stages in which the two cacti duel to the death, flinging bombs until only one remains. Here, a layer of strategy is also presumed, but in reality, matches quickly devolve into a screen of ping-ponging bombs. The bosses are more interesting, appearing on every tenth room. From giant hornets to weird, bulbous birds, these bouts are fun if sometimes overtly frustrating.

Indeed, the game’s whimsy belies a brutal sensibility, with most players likely giving up long before the 100th level is ever reached. Powerups, including speed and bomb enhancements, do little to prevent the next inevitable death. In fact, the best item is a blue flower that appears wherever the player was last defeated. Grabbing the item instantly cleans the screen of all enemies—even bosses!—and always reappears at the next misstep. It’s as if the developers knew their game hadn’t been properly fine-tuned and, rather than fixing those deficiencies, simply inserted this to artificially alleviate the body count.

These problems are regrettable for a game that, thanks to its cheeky nature, well-crafted graphics, and slick animation, makes a good first impression— a mix of Snow Bros. with a whisk of Bomberman, plus its own secret ingredient. But that initial enchantment soon withers to what becomes a repetitive grind; there’s no elegance to the mechanics, no sense of real progression, no satisfying or practical strategy. No style. Bombs are thrown. Bombs explode. Bombs dominate everything and, some might say, even undermine the entire experience by the end. It’s "rock-paper-scissors" without the rock, in other words.

And "bomb-paper-scissors," naturally, can only end in oblivion.--D

Saboten's environs are well-drawn and varied, even if the stages themselves play largely the same.

Falling enemies can leave the cacti seeing stars.

Bosses are also diverse, although they soon begin repeating (albeit in more difficult forms).

Later level designs force players to devise techniques not immediately obvious, such as "bomb-jumping" up walls.

The game's ending, for those few who reach it, suggest a sequel that never came. Or, more mundanely, it might simply be referring to the 'XX' levels that follow after the 100th.

Publisher: Tecmo

Developer: NMK

Release: 1992

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Snow Bros.

Platform: Amiga

Did these three receive help from the illustrious Sonic Team?!

Later backgrounds feel rushed, generic, almost place-holderish--maybe due to the game's dubious release status.

Defeating the boss of every tenth stage reveals a nice splash interstitial showcasing the next boss.

The "not-at-all self-congratulatory" main team. Although, to be fair, their adaptation is quite good.

The single-screen platformer often got slighted on consoles, appearing only in dribs and drabs across different systems. Not so with the home computer, however. A number of SSPs, from Rod-Land to Bubble Bobble, got numerous PC adaptations. And for Snow Bros., this Amiga version is especially interesting.

Namely for its story, which, like many Snow Bros. adaptations, opens in strict contradiction to the others. This time, there are no princes turned into snowmen, no Satan or King Scorch on the attack, no accursed sun that must be thawed. Rather, a girl is simply snatched from her cozy European village by an inexplicable monster—the game’s first boss. But God is kind (there’s even a Christian church in the background), casting down a lightning bolt on an unremarkable little snowman. This brings the little tyke to life, from which he then capers after the girl.

It’s an elegant opening to what’s an otherwise straightforward port—accurate and, on the surface, almost identical to its arcade counterpart. Players hop their heroes across platforms, lob shots at baddies until they’re packed into snowballs, and then cast them down at other critters. What’s different is the difficulty; offering both an easy and a hard mode, the game is much more generous with the extra lives than in other versions, giving everyone a realistic hope at reaching the game’s self-reverential ending. After showing the rescued girl hopping with her snow bro amidst an uncannily sunny valley, a long and ostentatious credits sequence rolls; here, the programmer’s skill in warping and scaling the game’s enemy sprites is put on display. And if that showboating isn’t enough, the game’s three key team members then appear as garish caricatures of themselves, an affectation meant more to service their egos than reward the player.

But developer pretensions aside, this is a fine rendition of the classic game. A few liberties are taken-- the process of spelling “snow” for a 1-up chance has been greatly simplified, completing every tenth floor now yields a spiffy piece of boss art, and some of the backgrounds for the upper floors seem oddly generic (rushed?) when compared to the originals. But for fans lacking access to the arcade game, this is an impressively faithful adaptation, offering the core experience without the bloat of other ports. No more, no less.

Unless one counts that scary credits scroll.--D

The opening, although somewhat nonsensical, offers a narrative elegance lacking in the other versions. That Snowman will soon be granted life...

Snow Bros.

Platform: Sega Mega Drive

So, the story: princesses get nabbed, then rescued, then are left to play savior for their now kidnapped snowman companions. And judging from the bottom picture, the foursome shares an interesting relationship...

The artwork is still weird...is that a Minion in the background?

The new levels have Puripuri and Puchipuchi playing the heroines. It's somewhat inexplicable, but their cute sprites are definitely an improvement over the vanilla brothers'.

The new levels' artwork is also peculiar. Why is everything here now set in a futuristic corridor/hangar? Is this a metaphor for the devil's undying influence through the ages?

The final boss--unlike King Scorch from the NES version, this foe's true identity isn't as easily confirmed. But if sources are to be believed, he's the literal devil himself.

Despite being a reasonably popular arcade game, Snow Bros. never received much support for the home. While fans might recall the somewhat obscure NES and Game Boy editions, owners of the Sega Genesis or Super Nintendo were left in the proverbial cold. It was a 16-bit game destined for an 8-bit screen, it seemed, like a vibrant Technicolor movie shown through a black and white TV. Disgraceful!

Unless one lived in Japan. Here, owners of the Sega Mega Drive (Genesis) got what many consider to be the game’s definitive edition—a convincing 16-bit conversion of the arcade hit that retains its feel and aesthetic. It also offers a load of new content; whereas the arcade game nixed the context in true “just-put-the-quarter-in!” style, the home port actually gives, to some degree, some semblance of a story. As told in the opening cutscene, two princesses are playing with their snowman pals when a demon (Satan?) appears overhead, overtaking the daytime sky. He swiftly snatches the two girls away, forcing the brothers to chase him (apparently) to the jagged tower drawn far into the background.

That’s one version of events, anyway. The NES game offers a rather different account involving a certain “King Scorch” who nabs the girls while transforming human princes Nick and Tom into the iconic snowmen. The 2022 remake offers yet a different telling, basing itself mostly on the NES story but switching out Scorch for “King Artich,” a fiend who, despite the name, fights while riding atop a giant fire-breathing chicken… (A cockatrice?)

More significant, however, is the Mega Drive version’s ending—once floor fifty is beaten, the princesses are rescued only for Nick and Tom to be nabbed in their place, leaving the damsels beating their breasts and forced to pursue. Yes, in a table-turning twist, players now take command of princess Puripuri or Puchipuchi for the game’s extra twenty floors, both of whom are somehow endowed with the exact snow-flinging powers. It makes little sense (and is likely why the remake adopts the NES account), but the girls’ sprite work is nice and the twenty new levels are fun enough. (Editor's note: Per info gained from a Snow Bros. fan, the Japanese manual explains the opening events a bit more sensically.)

Everything else, of course, is much the same as the arcade. The rules, based on gravity and trajectory, involve packing enemies into snowballs and then rolling them down platforms into other foes. It’s a mechanic that makes instant, intuitive sense; a natural fit for a genre based on 4:3 boundaries. Only a harsh difficulty—partly due to unfair platform traps and some incorrigible bosses—harm the overall fun factor. The password feature is a godsend.

So, it’s a good game…but is this iteration of Snow Bros. the definitive version, beating even the arcade original? Its (slightly) more forgiving challenge and extra content certainly suggest as much, but it remains a frustrating climb all the same; the twenty extra floors only make it harder. By contrast, the NES offers a more approachable challenge and, for those who care, a superior story.

Whichever version one opts for, always bring a friend! It’s the crisscrossing, zigzagging teamwork that kept people playing back in the day, ensuring those princesses actually got saved…and granting the game that timeless sense of exuberance still so compelling today.--D

Publisher: Tengen

Developer: Toaplan

Release: 1993

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Snow Bros.

Platform: NES

The square "wells" above are essentially traps--the player can't easily escape once falling into one. And it's really easy falling into one.

A cinema scene shows "King Scorch" nabbing one of the princesses. Oddly, he's not featured in the game itself.

Bubble Bubble might be the foremost representative of the single-screen platformer, but Snow Bros. carries more of its soul. After its release in 1990, the genre became inescapably influenced by the game’s mechanics and sensibilities; Tumble Pop, Saboten Bombers, Nightmare in the Dark…it’s hard not to find a succeeding one-screen platformer that doesn’t crib something from the Snow Bros. dynamic.

Which is not surprising; the game is fun. As snow siblings Nick or Tom, players must progress through 50-stages of hopping and snow-throwing, using gravity to their advantage. Indeed, the game’s genius comes in its core mechanic—pack an enemy into a snowball (really, snow boulder), then bowl him down the screen at other enemies for powerups and big points. Savvy players, learning the nooks of every level and understanding their foes’ behavior, can turn each arena into an almost Rube Goldberg-style machine, toppling henchmen from every corner of the map. It’s here where the game truly satisfies. The aforementioned powerups also heighten the fun by adding some much-needed speed to the heroes’ normally stodgy movements, plus strengthening and lengthening the efficacy of their projectiles.

Further variety comes with the bosses, who guard the chamber of every tenth stage. Some of these battles are fun; some, especially the dual-birds of level 30, come packed with unfair attacks that only repeated practice can realistically overcome. Level design, unfortunately, begins to feel repetitive as the game climbs into its final floors, with platforms placed in ways to intentionally trap the player while enemies descend for easy kills. As before, these moments don’t seem especially fair, and certainly snuff some of the fun found in the earlier stages.

Fans of the arcade original will find this NES port extra interesting, as Capcom/Soft House definitely took some liberties in its story and framing. The brothers, the game now explains, were once human princes before being cursed by the evil demon, King Scorch. This added context is both welcome but weird…considering the demon never appears during actual play. Nevertheless, the game’s mechanics, graphics, and sound all match the arcade in authentic, if undeniably 8-bit, fashion. A faithful, impressive conversion, overall.

But is it the best single-screen platformer on the system? Or, rather, of all-time? Being influential doesn’t always mean being the best, but for fans of the genre or those with an NES fetish, this is one cartridge (or ROM) well worth seeking out.--D

Publisher: Capcom

Developer: Soft House/Toaplan

Release: November 1991

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Snow Bros. (Jr)

Platform: Game Boy

Interestingly, this version eschews the typical "save-the-damsel" narrative for a more cryptic focus on the snow brother's world and primordial mythologies. As shown above, each time a boss is defeated, a tablet of prophetic import is acquired.

The ten new levels play like the others, but are harder to manage due to enemies that can now warp around the chambers at will, firing in any direction.

Snow Bros. Jr (Snow Bros. in North America) would have been better labeled “Snow Brother,” as only one snowman takes the stage in this adventure. Whether due to the Game Boy’s processor limitations or just the impracticality of offering cooperative play on a handheld device, Nick (Tom?) must climb the game’s fifty floors alone—not to save two winsome princesses, but his own kidnapped twin. Once the bro is rescued, ten bonus levels unfold, culminating in a battle against the sun itself.

It’s a weird story—one told through cryptic interludes spliced between the game’s six boss fights. Perhaps the manual explains more, but judging from the cutscenes alone, the sun seems to have lost its heart—becoming, well, heartless in its treatment of the world below. And who better to snuff out a star’s burning tyranny than a frosty snowman? It’s an odd if obvious metaphor, but one that at least grants the game some distinction over its console and arcade counterparts.

Otherwise, the experience in largely the same, just sloooowwwer…Nick seems to move at half speed compared to other versions, and he isn’t particularly quick in those, either. He also attacks more slowly, firing only two shots at once before the following “reload.” This intermittent delay doesn’t affect the mechanics much, but does rob the gameplay of that signature “zest” so intrinsic to the original’s appeal. Nevertheless, the proceedings still work as expected—first pack enemies into snowballs and roll them down into other foes, then collect the points and power-ups they leave behind. The original five bosses also return, albeit in less formidable form; players who struggled with other Snow Bros. adaptations might appreciate Jr's more manageable challenge.

Perhaps inevitably, Snow Bros.’s arcade, Mega Drive, and NES incarnations render this port all but irrelevant. Jr is simply slower, drabber, and less refined than its bigger brothers found on other formats. But, for diehard fans clamoring for yet another retelling of a game that originated with no story at all, this is worth a curious playthrough.--D

The original bosses return for this pea-soup retread, although they're not quite as brutal.

A bonus level is offered after every ten floors. It's as inconsequential as it looks, however.

Publisher: Capcom U.S.A., Inc.

Developer: Toaplan Co., Ltd.

Release: January 1992

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Sonic the Hedgehog

Platform: Master System

Second only to Nintendo’s Super Mario in terms of mainstream recognition, Sonic is the rare ‘90s video game franchise that has survived the climes of modern times, handedly outlasting his rascally mascot contemporaries as the years turned into decades. Even Sega, the Blue Blur’s corporate originators, has floundered where the hedgehog hasn’t; it often seems Sega lives on because of Sonic, not the reverse.

But for all his fame, the hero’s early history is still largely framed within his 16-bit games: Sonic the Hedgehog 1-3, Sonic and Knuckles, and Sonic CD. These fabled five are held in a kind of fond, reverential awe, the earliest accounts on record for the hedgehog’s considerable lore—a veritable, interactive Torah ofor the Sonic faithful. But Sonic was more than a 16-bit experience; Master System and Game Gear owners received a somewhat divergent gospel, a separate series of games both similar to their upscale counterparts, yet strikingly distinct. Games that, today, are deemed more apocryphal than appreciated.

Indeed, this rendition of "Sonic the Hedgehog," the first in a series of 8-bit games released across the Game Gear and Master System platforms, offers a different interpretation of the usual creed. In the 16-bit releases, stages were multi-tiered and beckoned exploration. Speed was paramount, platforming was secondary. There were inexplicable loop-de-loops and meta-pinball wizardry and floating mazes that spun against cascades of falling birds and neon fish. It was an exercise in flash over substance, some might say. But really, the games were simply a journey into the surreal—dynamic works of abstraction that compelled all who played.

But this 8-bit scripture paints a different picture, offering a game more straightforward, more linear, more deliberate. Here, precision platforming is better emphasized; tiered-exploration is rare. Environments are less exotic, more mundane—generically-devised “Bridge” and “Jungle” locales now join the more thematically rich Green Hill and Labyrinth Zones. Progression feels more utilitarian with presentation favoring function over form. Only the bonus rounds, with their bouncy, bumper-heavy, physics-defying antics, match the whimsy of the Mega Drive original.

The Sonic the Hedgehog series became a hit because of its 16-bits—this 8-bit retelling, no matter how clever or faithful, could never hope to overtake the preeminent edition. Unlike the competition between Super Mario 3 and Super Mario World, wherein the former could live, for a time, without facing an immediate replacement, Master System Sonic enjoyed no such luxury. It appeared not before, but amidst a graphical renaissance, and was thus ushered into instant irrelevancy. Gamers wanted the future, and Master System Sonic was but an inconsequential demake long before the term even existed.

But that was then. 8-bit graphics are now an aesthetic--an artistic choice--and Sonic is bigger than ever. If not a classic, this unsung romp remains a happy addendum to the hedgehog’s heritage, and fans owe it another chance.

As does Sega. If there's any justice, the company will do a Sonic Origins 2 dedicated directly to Sonic's full 8-bit legacy. The faithful should demand nothing less.--D

The game's bonus level sees a radical redesign from the 16-bit rendition--although the goal still involves "reaching the end," it's more about handling the tricky spring-physics than navigating a spinning maze.

Both versions still share a decidedly lethargic Sonic when moving uphill from after a complete standstill.

The Chaos Emeralds return for a total of six. This time, they must be found in the levels themselves.

Unlike its 16-bit counterpart, this version of Sonic provides an attractive map of Sonic's homeworld. Sega would later include a 3-D rendition of this same scene in 2022's Sonic Origins.

In one instance, the stage even scrolls vertically for a time. A missed jump means defeat.

Publisher: Sega

Developer: Ancient

Release: October 25, 1991

Genre: Platformer

Super Mario Land

Platform: Game Boy

Although no mainline Mario game is truly obscure, there is one title many flippantly disregard or simply overlook—the endearingly simple, or infamously basic, Super Mario Land.

At first glance, the game seems deceptively like the original Super Mario Bros. The graphics bear a similar likeness, the mechanics are largely the same, the levels are still overly linear, and even backtracking is kept impossible. Indeed, in a certain sense, it’s the original’s true sequel.

But there’s a strangeness, an almost eerie, unseemly feeling, that pervades the experience. Like chomping into an apple that’s gone a little too soft, or a banana that seems a little too brown. Here, Mario’s journey is a cascade of gray. Koopas (called Nobokons here) explode when stomped. Robots march along the seashore while flying saucers serve for trees in the background. Fireballs have been replaced with “Superballs” that bounce once and then fly uselessly into the air. Moai statues bounce and pounce like springs. Bowser has been replaced by an alien (Tatanga). Even the princess isn’t the same. (Hi, I’m Daisy!)

In short, the game feels oddly off-brand, as if contracted to a third-party that didn’t fully understand the property, or like a random fangame that veered into the weird. And those intuitions are not altogether wrong…

Super Mario games were usually the product of series creator Shigeru Miyamoto and his R&D4 development team. But circa 1988, another division, R&D1, was scurrying to develop the Game Boy handheld and its initial lineup of titles; wanting an easy showcase of the system’s abilities, Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi told the team to design a Mario platformer. Look, scrolling graphics! Lots of moving characters! Catchy music! Genre-blending gameplay! And so, Super Mario Land was born—not from the hands of Miyamoto’s team, but from the Game Boy group only vaguely familiar with the series’ canon and mythos. Ultimately, R&D1 made whatever game it wanted, using only the first Super Mario Bros. as a reference.

Which explains, of course, the slight cognitive dissonance many experience when playing the game, that familiar but slightly off-putting feeling as Mario grabs an invincibility star or dives down a pipe or rides atop a hopping boulder. The question, then, is whether these differences, some more subtle than others, improve or detract from the overall experience.

Fortunately, the passage of time has been kind to this one.

No doubt, Super Mario Land was popular in its day, but it also had the advantage of being a launch game for an exciting new novelty. As years passed, Mario’s first Game Boy adventure quickly became dismissed in light of better titles, whether designed for the handheld or its bigger console brothers. That dismissal eventually became derision, with critics retroactively declaring the title as too short, too quirky, too inconsequential. And they weren’t altogether wrong.

But today, where so many Mario games feel cut from the same, blasé template, when the franchise’s last major new villain was Wario from 1992 (thanks to Land’s sequel, no less!), when other experimental off-shoots like Super Princess Peach and the Wario Land series have been left to languish if not outright die…Mario Land’s distortions of the traditional formula now seem daring, even brilliant. Mario in a submarine, blasting marine life? Fun! Mario in a biplane dogfighting aliens? Weird…but fun! The four kingdoms themselves set in real-life locations, from Egypt (Birabuto) to China (Chai)? Neat!

Modern Mario games could use a sliver of this unabashed kookiness.

The good news is that the unseemly hijinks continued, somewhat, in Super Mario Land 2; the sadness is that Nintendo eventually abandoned the (2-D) Land games and timeline altogether (a few nods in Mario Maker 2 notwithstanding), saving only Wario and Daisy before never looking back. Two characters got spared, but not the series’ quintessential quirk—an ingredient that makes Super Mario Land ever-special over the passage of time, a symbol of an era in which games were crafted with a more freehand approach and corporate rule didn’t dictate all.

It’s hard not to yearn for the old Nintendo.--D

Boss fights are simple but serve their purpose.

Stages 2-3 and 4-3 are horizontal shooters. Pretty fun ones, too.

Flying saucer trees?

Aww, but that's Luigi's girl...right?

Publisher: Nintendo (R&D1)

Developer: Nintendo

Release: July 1989

Genre: Platformer

Tumblepop

Platform: Arcade

The single-screen platformer is rife with classics and also-rans. Taito gave us the genre-defining Bubble Bobble. Toaplan gave us the seminal Snow Bros. And Data East gave us Tumblepop, a game as generic as its mishmash of a name implies.

Well, that’s not entirely fair. Though the plot is almost non-existent, and the game’s twin heroes distinctly unremarkable, its primary mechanic doesn’t actually suck. Well, it does, but in a good way—by inhaling enemies into an overpowered vacuum (think Ghostbusters or Luigi’s Mansion), the player can then spew them back at other attackers. Inhaling multiple baddies in a single go releases an even more rapacious discharge that then ping-pongs across the screen, piercing through the remaining foes. It’s a dynamic doubtlessly cribbed from Snow Bros., but with an important distinction; more than just being stunned and tossed, baddies can now be momentarily held, carried, and dispensed at will. It might seem incidental, but this added wrinkle makes for a faster, brasher, more dynamic game.

Indeed, the vacuum might even be too powerful. Its reach is generous, capable of yanking foes and items through walls and other obstacles. Skilled players can literally bound about the screen, sucking up the stage’s inhabitants and collecting their spoils before the time limit has barely budged. And really, they're compelled to, as the enemies can only be held for so long before breaking free for further mischief. Baddies flattened by an attack will either drop point-granting baubles, the occasional speed, range, and strength-boosting upgrade, or a random letter--spelling “Tumplepop,” triggers a cursory bonus stage.

As for why these two kids are battling clowns, ghosts, robots, and other such monsters, the game never directly explains. In a nod, perhaps, to Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, the scamps travel to eight unique spots across the globe, vacuuming monsters as if everything were self-evident. Once the planet has been cleansed, they head into outer space for another two rounds of battle. A mad scientist-type attacks, loses, and well…the end. Congratulations.

A dull aesthetic reinforces this flimsy narrative, imposing its milquetoast heroes against a swath of bland backdrops. Players will visit such illustrious locales as Rio and France, but most will hardly notice. The enemies are no better, feeling inconsistent with their environments as if snipped from a different game. The ten bosses are more memorable but, at best, only vaguely represent their homelands. Moreover, the animation is merely serviceable, the stages overly crowded and compact, and the music, although catchy, is really just the main theme remixed nine separate times. All this, combined with the already derivative gameplay, leaves Tumblepop feeling like a churn n’ burn release—a hastily spun confection originally intended to fill the gap between bigger, more prestigious titles.

But, it’s still fun. And very accessible. And the difficulty curve is much fairer than some its more famed single-screen competitors. It might lack the overall warmth and charisma that made, say, Bubble Bobble an instant classic, but as a rushed introduction to the genre, Tumblepop might just be the easiest way in.--D

Joe and Mac characters? An interesting foreshadowing, indeed...

Interstitial cutscenes add to the fun. Right?

Publisher: Leprechaun Inc.

Developer: Data East

Release: 1991

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Enemies, at best, only vaguely connote the lands they represent.

Boss battles can be fun...