Born on December 15th, 1973 in Nice, Alpes-Maritimes, France, Surya Bonaly is the adoptive daughter of two white parents, although she, herself is black. Her biological father is from Ivory Coast, West Africa, and her biological mother is from Réunion, an island off the coast of Madagascar. Bonaly is best known for her figure skating career however, she also trained as a gymnast in her younger years. She gave up gymnastics believing that she could have a more successful future as a figure skater.

Bonaly is often written by popular media as the “rebel” of figure skating for acts such as performing an illegal one-legged backflip during the 1998 Olympics in Nagano and refusing her second-place finish during the World Championships in 1994. Christine Brennan, a Sports Journalist and Commentator with ESPN referred to Bonaly as the “ultimate outsider in a sport where you have to be an insider.”

Ice skating was developed as a means of transportation in the Netherlands early in the 1200s. A few centuries later, it was introduced to British aristocrats, and ice skating was soon deemed an activity for the wealthy (Adams, 2010). Over time, the sport of figure skating was developed by Jackson Haines who incorporated dance movements and music into his skating. In these early years, figure skating was dominated by white males (Adams, 2010). When women began participating in the sport decades later, it was still clearly a sport created by and for upper-class citizens (Adams, 2010). During the 1800s and much of the 1900s, this meant being white (Burgess-Proctor, 2006).

To this day, figure skating remains a sport dominated by white women (Adams, 2010). In fact, Debi Thomas and Surya Bonaly were the only black women figure skaters to compete in the Olympics until the Winter Olympics held in PyeongChang, South Korea in February 2018 (Abney, 1999). Such low representation of black women at the highest level suggests that the institution of figure skating may have systemic barriers preventing black women from excelling at this sport. Elling and Knoppers (2005) demonstrated that reduced participation of ethnic minority females in many sports can be attributed to barriers such as historic unequal opportunities to participate in sport that has contributed to both a lack of desire and a lack of perceived ability to participate in the present.

As an expensive sport, black people not only had be allowed to participate in it, but they also had to be wealthy enough to afford it. As such, given the racism that black persons have been subjected to that has inhibited their participation in both sport and society as a whole, it is conceivable why there remains such low representation even today.

Growing up in a white and fairly affluent family, Bonaly was afforded the privilege she needed to get on the ice and compete to become a three-time World Championship silver medalist and a three-time Olympian. Despite her upbringing however, the media refused to acknowledge her as anything other than a black body to be studied as an object (Hoberman, 1997). Even more, Bonaly’s parents and coach contributed to Bonaly’s media portrayal as an “othered body” by originally telling people that she was born in Réunion and left on a beach because they thought that it sounded more exotic. They believed that portrayal of Bonaly as an exotic body would give her more coverage in media and help her career as a figure skater.

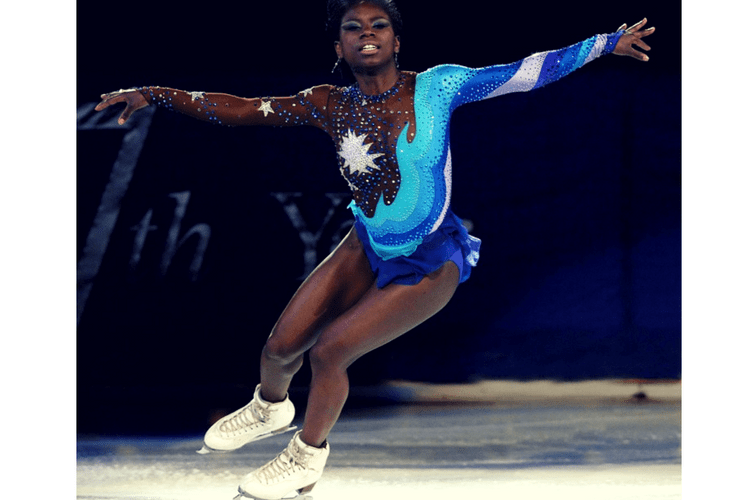

Figure skating is often described as a sport requiring the perfect mix of both elegance and athleticism. Bonaly did not fit the “dominant Anglo-ideology of what sorts of body form an Olympic figure skater,” as written about by Krause (2008). The ideal figure skater is built around the concept of white femininity characterized by being slender, petite, graceful, and not overly muscular (Krause, 2008).

Bonaly, on the other hand, was written about in popular sport media as a “great athlete” who was shorter, thicker, and more muscular than her white counterparts. This depiction of Bonaly directly counters the traditional white femininity that had defined the “ice princess” ideal look that judges, fans and the media were looking for (Krause, 2008). However, historically so few black women have been allowed to participate in figure skating, and the black body had never had the opportunity to work itself into the definition of an ideal figure skater which ultimately placed Bonaly at a disadvantage from the beginning of her career.

While figure skating is also often praised for how it has continued to become more athletic over the years, Bonaly was described as too athletic, lacking a certain grace that is required of a figure skater. During an interview, Bonaly went so far as to allude to potential racism she was facing by saying “Maybe I won’t be accepted by a white person. But, if I’m better, they have no choice.” What Bonaly is hinting at here, is the preconceived notion that judges had about her even before they watched her skate. There was this idea that no matter what, she would have had to do more in order to gain more technical merit points as her presentation points would never quite match those of the white feminine bodies she was competing against.

This describes the inherent racism behind the sport itself. Bonaly constantly faced negativity from judges as she did not fit in to their norm. Being black did not correlate with their idea of being graceful as characterized by the white feminine body. This clearly demonstrates that the dominate white culture determines who is and is not allowed to be exceptional and that definitions of what is acceptable behaviour can change based on who is performing it (Jackson, 1999).

Sports media is in a very powerful position to perpetuate this idea by defining and reproducing black athletes in relation to the dominate white ideology (Littlefield, 2008). In Bonaly’s case, the media was constantly deciding when Bonaly’s athleticism was allowed to be astounding, and when it was disrespectful to the culture of skating itself. The latter was discussed most notably, in Bonaly’s performance of the back-flip.

The first perceived slight to the skating culture that sports media produced was Bonaly’s performance of a backflip during a practice round prior to competition. It was referred to as a strategy to distract others and throw them off their game. This harmful media portrayal of her signature jump depicts Bonaly as a conniving villain doing all that she can to win and compares her intentions to animalistic malice (Bernard, 2016).

Moreover, the media attributed her ability to do a one-legged backflip on ice to her muscular build which they then attributed to her blackness often leaving out her training as a gymnast or throwing it in as an after-thought. Descriptors focused solely on her physicality undermine the hard work that Bonaly had to do to get to the elite level of figure skating by attributing her jumping skill to a phenotypic advantage that while not real, has been reproduced by the media so often that the myth has become a perceived reality (Entine, 2000, p. 18).

Also often left out, is that Bonaly must have been extremely intelligent to not only correctly perform a backflip on skates, but to do so on one leg and without injuring herself in the process. The technicality of performing such a jump would have required deep thought and planning, but the attribution of the jump solely to her physical features perpetuates a culture of attributing success of black athletes to physicality rather than intelligence (Fries-Britt & Griffin, 2007). Whether intended or not, this contributes to the construction and perpetuation of the ideology of white people as smarter than black people.

When discussing her decision to do a backflip at the Olympics, Surya commented, “I wanted to do something to please the crowd, not the judges. The judges are not pleased no matter what I do, and I knew I couldn’t go forward.” Bonaly’s remark points not only to the system that rejected her, but also signifies her bravery for performing in a way that made her happy regardless of what the system thought.

In interviews, Bonaly has never directly mentioned that she experienced racism, however, black athletes may sometimes feel like they do not have a place to voice their opinion because they do not want to be identified as “the problem.” This may be particularly true as Bonaly was performing in a sport where she was one of the only minorities competing at the time.

Despite these setbacks, Bonaly refused to downplay her strengths and differences. Her style and skill was perceived as threatening to the white culture of figure skating, but she unapologetically performed her blackness despite an entire culture of sport trying to white-wash her to meet their norm. Bonaly deserves a larger stage to share her experience as a black woman in a very white sport. She deserves an opportunity to rewrite the story of her “rebellious” moment as one of drive, dedication and hard work.

References:

Abney, R. (1999). African American women in sport. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 70(4), 35-38. DOI: 10.1080/07303084.1999.10605911

Adams, M. L. (2010). From mixed-sex sport to sport for girls: The feminization of figure skating. Sport in History, 20(2), 218-241. DOI: 10.1080/17460263.2010.481208

Bernard, A. A. F. (2016). Colonizing black female bodies within patriarchal capitalism: Feminist and human rights perspectives. Sexualization, Media & Society, 1-11. DOI: 10.1177/2374623816680622

Burgess-Proctor, A. (2006). Intersections of race, class, gender and crime: Future directions for feminist criminology. Feminist Criminology, 1(1), 27-47. DOI: 10.1177/1557085105282899

Elling, A. & Knoppers, A. (2005). Sport, gender and ethnicity: Practices of symbolic inclusion/exclusion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(3), 257-268. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-005-4311-6

Entine, J. (2000). Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We are Afraid to Talk About It. New York: Perseus Books Group.

Fries-Britt, S. & Griffin, K. (2007). The black box: How high-achieving blacks resist stereotypes about black Americans. Journal of College Student Development, 48(5), 509-524. DOI: 10.1353/csd.2007.0048

Hoberman, J. (1997). Darwin’s Athletes: How Sport Has Damage Black America and Preserved the Myth of Race. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Jackson, R. L. (1999). White space, white privilege: Mapping discursive inquiry into the self. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 85(1), 38-54. DOI: 10.1080/00335639909384240

Krause, E. L. (2008). “The bead of raw sweat in a field of dainty perspirers”: Nationalism, whiteness, and the Olympic-class ordeal of Tonya Harding. Transforming Anthropology, 7(1), 33-52. https://doi.org/10.1525/tran.1998.7.1.33

Littlefield, M. B. (2008). The media as a system of racialization: Exploring images of African American women and the new racism. American Behavioural Society, 51(5), 675-685. DOI: 10.1177/0002764207307747