David Bowie was a performer for the ages

It’s been a tough few months for the music world. The losses have come fast and hard: former Stone Temple Pilots singer Scott Weiland; Lemmy Kilmister and Phil Taylor of Motorhead; Eagles guitarist and songwriter Glenn Frey; former Rainbow and Dio bassist Jimmy Bain; and most recently, Earth, Wind & Fire founder Maurice White.

But personally (and this surprised me) it’s the death of David Bowie that has had the most immediate and lasting impact.

The news of his passing hit me hard and strange when it came over my cell phone’s news feed in the early morning hours of Jan. 11. I had spent the better part of the previous evening listening to the single “Lazarus” from Bowie’s new album, “Blackstar” and combing through his back catalog of music and videos, a treasure trove of the classic, the bizarre and the woefully misguided that I had become newly fascinated with in the wake of his reemergence. Before I went to bed that night I made a mental note to order “Blackstar” and several other Bowie albums.

When the news came through around midnight, it felt like a bad joke: an artist who I had admired but undervalued for years, whose work I was finally ready to dive into, was gone, suddenly and without explanation, on the eve of a triumphant return to form.

Like most kids who came of age in the 1980s, my first exposure to Bowie was the video for the song “Ashes to Ashes,” which was played in heavy rotation on MTV during its formative years. Though I was too young to have any idea of his impact on the music and culture of the previous decade, one look at the fantastically strange sight of Bowie’s skeletal frame traipsing through a 21st century wasteland dressed up as a decadent European mime was enough to seal those disturbing, hypnotic images in my mind forever.

Like his character in that video, Bowie traveled through the entertainment world of the 1970s like a detached and homesick observer of the waste and folly of all human endeavor, his own included. But as singular as he was, Bowie was also a product of his time. He was part of a generation of punks, soul ramblers and English blues freaks, visionaries and wordsmiths rooting around in the past and tunneling through into the future. He was among the fools and mutants too weird for their times who found something holy and created their worlds anew.

For Bowie, that new world involved not only music, but performance. He used his training in mime techniques and fascination with Japanese Kabuki culture to foreground what musicians have always done but rarely acknowledged: create characters for the stage that are far more interesting than their everyday selves.

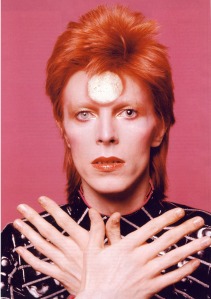

Of course, Bowie’s day-to-day existence during the 70s was fairly eventful as well. With his scarlet bouffant and shaved eyebrows, he was both repellent and beautiful, a cadaverous alien without race, class or sex who existed on a diet of cocaine, milk and red peppers. And he looked as comfortable in a dress as he did in a leather jacket.

But while the press and most fans focused on Bowie’s otherworldly otherness, they often missed the very human sorrow and yearning, not to mention the sheer songwriting skill, of his best work. Listen to any of his great early songs like “Man Who Sold the World,” “Life on Mars?,” “Moonage Daydream,” “Starman,” or “Changes” and what you hear is a deeply empathetic soul trying to make sense of the confusing tangle of 20th Century culture, with its soul deadening technology and information overload.

But ultimately, whatever Bowie represented in the past is not nearly as important as what he was in the end — a man who used the enormous creative powers he had been gifted with to take an unflinching look at impending death—that ultimate unknowable mystery—with warmth, rude humor, and not an inconsiderable amount of anger.

I don’t know if “Blackstar” is a great album, but it is possibly the most perfect album for its time and circumstances. A hypnotic mesh of digital witchcraft and propulsive alien jazz, its mad, swirling pools of saxophone, bass, drums and guitars are both deeply unsettling, darkly humorous, and oddly beautiful. It may be the most challenging, deeply felt music of Bowie’s career.

That’s no accident. Bowie knew he was dying and that knowledge seems to have freed him. “This way or no way,” he cries in “Lazarus.” And in “Dollar Days” he offers this remarkable look at the closing down of life’s possibilities, even as the will pushes on.

“It’s all gone wrong but on and on

The bitter nerve ends never end

I’m falling down

Don’t believe for just one second I’m forgetting you

I’m trying to

I’m dying to”

In the end, the plastic showman, the celebrity worshipping soulless actor turned out to be the most honest, most real and bravest talent of his era.

The world is a brighter and far more interesting place for his having passed this way.

Leave a comment