Aldous Huxley

In June 2016, I attended the annual conference of the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature (SSML). There I read my fiction and presented on “The Space and Place of Western Minnesota Writers.” Since I had just been accepted into law school, throughout the conference I kept drifting to the question of how I could combine my passion for literature with my interest in law. (Though, of course, as every good lawyer knows, good legal writing is also good creative writing). Then an idea came to me: I could study judicial references to dystopian literature.

Brave New World (1932)

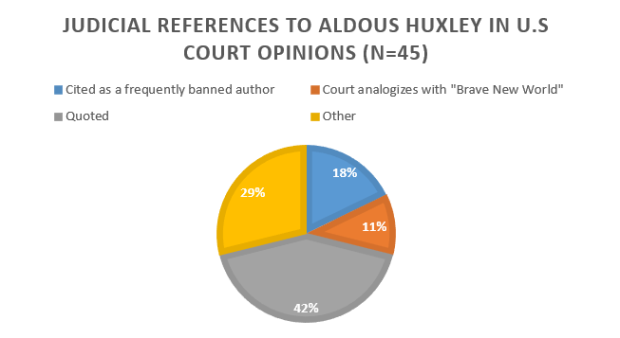

Someday I’ll expand this to include George Orwell and 1984, but as a test-run, I decided to focus on Aldous Huxley, the English author of Brave New World (1932; “BNW”) and The Doors of Perception (1954). Given BNW’s dystopian bioethics, I assumed it would be leveraged as a rhetorical device—the specter against which parties framed discussions of modern medicine, drugs, and government control. So, using Lexis-Nexis, I ran a keyword search for “Aldous Huxley” and found 45 opinions. (The keyword “George Orwell” returns 210). Twenty-nine of these were from federal courts, with the rest coming from the states. I then coded the keyword-reference per its context—i.e. whether the opinion analogized with BNW, referenced book bans, quoted Huxley personally, or referenced Huxley in some “other” context. This last catch-all included references that were not in any way unique or meaningful (e.g. a reference to Timothy Leary’s friendship with Huxley or a court’s takedown of a brief appealing more to literary than legal theory).[1]

What I discovered is that, in fact, very few cases analogize with BNW (n=5)—and while it seems to be the refuge of the dissent, it is the cause of eye-rolling for the majority.[3] Book banning cases will often include lists of frequently challenged books, placing BNW alongside Slaughterhouse-Five, Fahrenheit 451, etc. (n=8). The plurality of cases merely quote Huxley, either in epigraph or to make a point in-text (n=19). They tend to use one of five quotes:

- Generally: “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” (n=8)

- Re: Copyright: “Parodies and caricatures are the most penetrating of criticisms.” (n=4)

- Re: Excusing Inconsistency: “Consistency is contrary to nature, contrary to life. The only consistent people are the dead.” (n=3)

- Re: Dogs: “To his dog, every man is Napoleon; hence the constant popularity of dogs.” (n=2)

- Because a Law Clerk Made a Bet: “There are things known, and there are things unknown, and in between are the doors of perception.” (n=1) [3]

Given the small sample size, admittedly, this survey lends itself more to being a curiosity than a window into how courts use literary authority and rhetoric. But, as a test run, it offers guidance a larger-scale project might take. For example, by adding George Orwell’s work to the mix, one could use similar coding here but distinguish between references to 1984, Animal Farm, and the broad Orwellian themes of government surveillance and political language. Interestingly, one could also record whether such references are more likely to appear in dissenting opinions (where, I’d wager, judges lean more on rhetoric than logic).

What are your thoughts?

[1] Leary v. United States, 383 F.2d 851, 857 (5th Cir. 1967) (“[Leary] said that he formed a religious research group after returning to Harvard University, and with the help of Aldous Huxley, he experimented with certain psychedelic drugs.”). State v. McCord, 753 S.W.2d 641, 643 (Mo. App. 1988) (“McCord fails to cite any specific provision, by article and section number, of the U.S. Constitution or the Missouri Constitution. Although his brief contains some case citations, most of the brief consists of references to, and quotations from, such writers as Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, Aldous Huxley, C.J. Jung, William James, Plato, Sigmund Freud, Adam Smith, Edmund Wilson, Thomas Paine, Alexis de Tocqueville, William Shakespeare, Robert Burns, Walt Whitman, John Dewey, A.M. Schlesinger, Jr., and S.I. Hayakawa.”).

[2] Compare Nelson v. Krusen, 678 S.W.2d 918, 932 (Tex. 1984) (Kilgarlin, J., dissenting) (“Although today’s society is not the genetically controlled one anticipated in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, a doctor’s power to control genetic information, without restraint, may have subtle, far-reaching and devastating effects on family planning.”), and Surrogate Parenting Associates, Inc. v. Commonwealth, 704 S.W.2d 209, 216 (Ky. 1986) (Vance, J., dissenting) (noting of new biomedical technology that “[t]he Brave New World of Aldous Huxley seems to be upon us.”), with State v. Martin, 955 A.2d 1145, 1154 (Vt. 2008) (rejecting the idea of an “inexorable march from DNA databases like Vermont’s to a dystopian future of eugenics, gene-based discrimination, and other horribles worthy of Aldous Huxley.”).

[3] State v. Berroa, 6 A.3d 1095 (R.I. 2010) (quoting Huxley in an epigraph in an opinion holding that the defendant’s charges of drug possession and conspiracy were based not on “things known” but inferences, i.e. “perception”).