“I have discovered the marvelous qualities of my shadow. Lately it has been detaching itself from me by virtue of its powers of flight.” —Leonora Carrington in a note to filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky

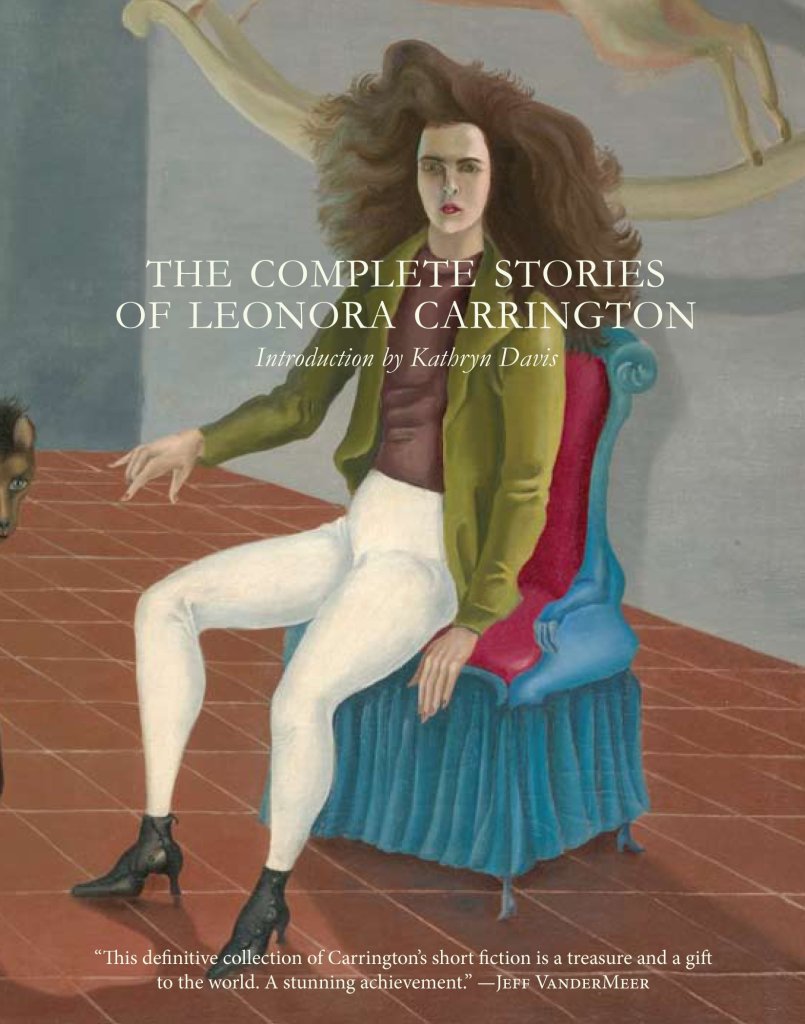

Leonora Carrington, the Surrealist artist who passed away in 2011 at the age of 94, once said that she wrote for others and painted for herself.The publication of The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington in 2017 by the (very fine) Dorothy Project drew much-deserved attention to the delights of her fiction. It also offered an opportunity to consider Carrington’s stories in relation to her better-known visual work. The story “The Debutante” (1937-1938) nestles snuggly into painting from the same year, The Inn of the Dawn Horse (1937-1938), chosen for the cover of The Complete Stories. This affirms the consistency of Carrington’s themes and style across media. Upon closer consideration, however, these modes of expression are often less congruous than they initially seem. This bears out Carrington’s response to Marina Warner when asked about the relationship between her paintings and written fiction: “I haven’t been able to reconcile image world and word world in my own mind.”

Carrington was prickly when it came to interpretation of her visual work. She described its ideal reception in an artist’s statement from 1975: “Once a dog barked at a mask I made; that was the most honorable comment I received.” Carrington’s paintings evoke esoteric symbolism, a syncretic scramble of cyphers drawn from the Tarot, Kabbala, alchemy, and Celtic mythology. Reading Robert Grave’s The White Goddess (1948) influenced her profoundly. When Carrington spoke of painting for herself, she meant a polyvalent self jostled by many ghosts and animal familiars. Her “inner bestiary” multiplies modes of perception. The paintings remain in varying states of tentative becoming. They evade direct comprehension.

Carrington created between 1500 and 2000 works of visual art, and scholars—Whitney Chadwick and Susan Aberth, the most probing among them—have attended to a portion of her prolific output. The body of work contains many murky, twilit paintings, ciphers; many that hold the traces of a dark struggle, or that seem unfinished or unresolved. Those are the paintings, one would suspect, that she made for herself. One such painting is Samain (1951). It conjures up a peculiar sorority. I’ve set alongside Carrington’s short story “The Sisters” (1939). While separated by a dozen years, the choice for comparison is based on thematic affinities. The space between these two works leaves generous room for musing, but far less for sustained argument.

While story and painting share fairytale qualities, verbal and visual signifiers carry psychic charges and sensory enchantments in distinctly different manners. Even so, Carrington’s images and words don’t always function as one might expect. It is the black marks on the white page that are most painterly. Her purpling of prose summons the senses. Stories, like “The Sisters,” are encrusted in detail, choked by pigment and heavy perfume.

When Carrington did have more literal stuff to work with–paint, surface, brush–feathers aren’t as soft or skin as rosy on the canvas as they are on the page. Paradoxically, it’s the stories that embody their subjects plumply. The paintings often stretch bodies thin, seeming to strive, even, to shed them. The stories often address the matter of flamboyant forays of fancy while the paintings often deal with escaping ghosts and immaterial shadows. The verbal signs are lodged in dense matter while paint attempts to free itself of its material condition, fleeing toward the mystical or metaphysical. In “The Sisters,” at least, abstract signs serve the sensorium. And in Samain, material marks cast shadows.

Carrington’s short story, “The Sisters,” is a wicked slip of a Gothic tale with startling images piled up like mishandled fruit. In the spirit of high parody and in a mere six pages it stuffs in way too many of the familiar tropes of the ghastly genre: a letter announcing the arrival at stormy twilight of a fallen aristocrat (Jumart) at a decrepit mansion with an attic imprisoning a pale and vulnerable maiden with vampyric tendencies (Juniper) eclipsed by her cruel doppelgänger possessed by perverse and decadent appetites (Drusille)…

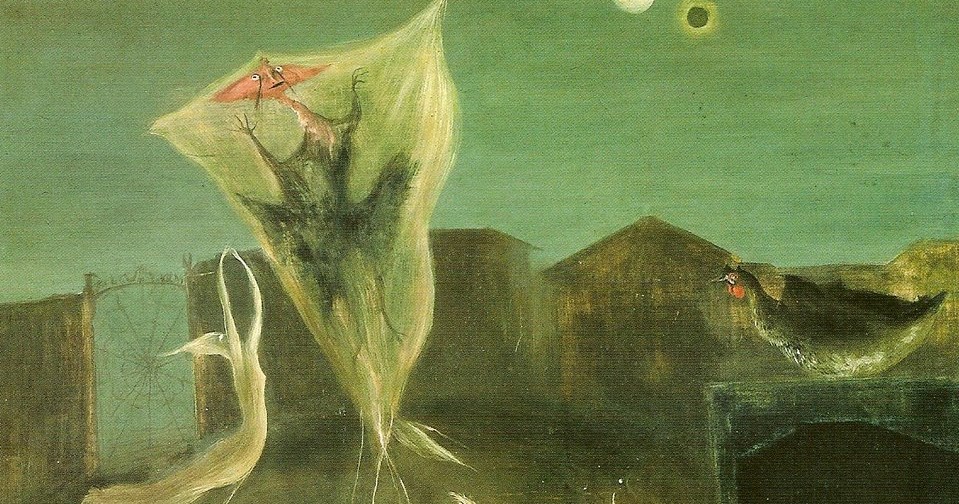

So. The ignoble Jumart has written to his lover Drusille in anticipation of their immanent reunion. The name of the dethroned and destitute king refers to the bastard offspring of a bull and a she-ass. He is nothing if not a ridiculous homme-enfant. Drusille waits for him a wild garden on what promises to be, indeed, a dark and stormy night. Around her, bloated streams carry off flowers, crushed butterflies, and small birds like so many ruined virgins. Drusille cackles with glee at the little perished bodies. “The Sisters” is populated by more than its share of dead birds. The story begins with torturing tugs against flight.

When the sun slices through the clouds, dark Drusille goes inside, crossing the threshold from the untamed realm to the domestic. She hurls insults at her maid Engadine, who is in the thick of preparations for the lovers’ reunion. She scents scarlet sheets. She stuffs melons with larks and suckling pigs with nightingales. Drusilla climbs a winding staircase, key in hand, toward the house’s hidden room. To no Jane Eyre reader’s surprise, there’s a madwoman trapped in the attic. Drusille’s sister, Juniper, is confined to the garret crawling with rats, bats, and spiders. The delicate Juniper, evergreen, is Drusille’s feral other; a hybrid girl-bird aching with unfulfilled yearning. Juniper requests a candle. Its light dramatically reveals her in stark chiaroscuro: Her body was white and naked; feathers grew from her shoulders and round her breasts. Her white arms were neither wings nor arms. A mass of white hair fell around her face, whose flesh was like marble. She begs for a bit of red (wine or blood?) and her sister offers only water. Juniper is desperate to see the new moon. The word “moon” flickers on the page, appearing again and again in a mere few lines. Drusille departs. In a breathless rush to meet the arriving Jumart in the garden, she neglects to lock the attic door behind her, unleashing doom.

Jumart enters the scene, a sartorial spectacle: His long, iron grey beard flowed over his green satin coat embroidered with butterflies and the royal monogram. On his superb head he wore an enormous gold wig with rose-coloured shadows, like a cascade of honey. A variety of flowers, growing here and there in his wig, moved in the wind. The enchanted Jumart swoons, while Drusille fills increasingly with dread. The fruits in the trees appear to her to hang like “little corpses.” When she complains of a headache, Jumart replies [with the story’s best line]: “I shall eat your migraine.” As the lovers retire inside to their hedonistic feast, the scene shifts to the kitchen and Engadine’s tireless labors.

The vampyric Juniper has escaped and comes after her red, which she finds at the peril of the ill-fated maid Engadine. Throughout the story the word “red” appears like drops of blood on paper. While Juniper sucks at Engadine’s neck, her marmoreal flesh grows warm. She glows like sun-struck snow, flashing peacock colors. She crows like a raucous cock and makes her winged escape toward the silver moon. The story ends abruptly, no moral in sight, with the tableau of the Drusille and Jumart surrounded by the glut and gore of their bacchanal heaped around them: Drusille’s hair moved like black vipers, the juice of a pomegranate dripped from her half-open mouth. Meat, wine, cakes, all half eaten, were heaped around them in extravagant abundance. Huge pots of jam spilled on the floor made a sticky lake around their feet. The carcass of a peacock decorated Jumart’s head. His beard was full of sauces, fish heads, crushed fruit. His gown was torn and stained with all sorts of food. Jumart is an ersatz bird, engorged, abject. The bawdy tale has burst at the seams. Phosphorescent Juniper, the changeling, has made her exit on the wing.

“The Sisters” overloads the senses. The prose is whipped up of the same frothy stuff as its subjects. The palette is lavish, with no fewer than thirty color terms (fierce yellow, lilac, scarlet, rose, snow white, wine red, silvered black…) in the space of its few pages. The story growls and shrieks and slams and sucks. The flavors are too numerous and rich to name. Cloying scents of jasmine and patchouli and musk hang heavily in the air. At its ending, the story lands in a puddle of unctuous confiture.

Carrington once drew this analogy: “Painting is like making strawberry jam–really carefully and well.” In light of the sauced and sugared passages of “The Sisters,” the simile better suits Carrington’s prose than her painting. But what Carrington might have been after when she evoked preparing jam in reference to painting is a more subtle transfer of energies, something closer to the scent of the word “berry”–not so much the glutinous stuff of pulp and thickened juice but a heady, alchemical sublimation. Like a less ghastly Juniper, Carrington was in pursuit of the tiny aromatic particles that escape on an updraft of air.

Carrington was partial to the medium of egg tempera. The concocting of yolk, vinegar and powdered raw pigment was a ritual that for her involved not so much the materia prima of paint but rather the ingredients for alchemical transformation. Alchemy was the subject that determined so much of her subject matter, and loomed largest in her cosmology. When laid onto wood panel, tempera paint dries into a matte, powdery surface well-suited for registering ineffable entities—light spirits of “snow, dust, and cinnamon,” to use Carrington’s phrase from her novella, The Stone Door (1977). In Carrington’s case, what lay just beyond the grasp of the five senses ultimately prompted a shift from the stuff to the stirring of spirits.

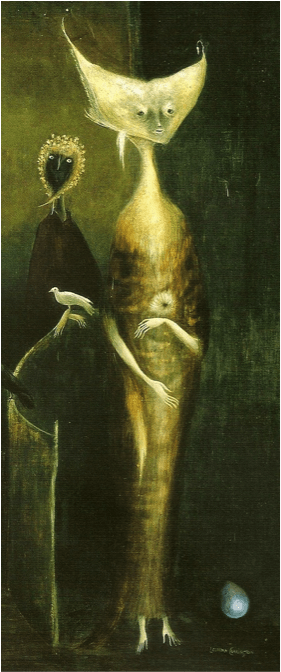

The painting Samain (1951) shares much with “The Sisters”: staging, uncanny doubling, stark contrast of illumination and obscurity, and most significantly, the struggle between earthbound captivity and the power of flight. The title refers to the Celtic All Hollow’s Eve, coincident with the Mexican Day of the Dead, marking the passage from summer to winter. On this night the membrane between the mundane realm and the world of spirits is particularly thin, enabling exchanges of the subtlest sort to occur. In the painting, two moons—one white, the other black and rimmed in the fire of the solar orb it eclipses—gleam in the sky like mismatched pearls.

Viewers find themselves in a shadowbox, again inside the confines of a walled garden, but now in the company of ethereal spirits in states of flux. The delicate cobwebbing of the gate suggests that witches, wild sisters, preside here. Animal familiars and hybrid beasts sprout tridents, claws, whiskers, and horns. Once glimpsed, souls light as smoke flicker in and out of eyeshot.

Carrington’s favorite paintings were prehistoric bison floating on torchlit cave walls. She reaches back to that cave, back beyond rationally determined phenomena and linear historical time to right imbalances of power (between male and female, civilization and wilderness). Her images arise from a leveled symbolic field. Human beings are revealed to be nothing more nor less than animals. As she writes in The Stone Door: Sorcerers and alchemists knew about animal, vegetable, and mineral bodies. They hack away the crust of what we have forgotten and rediscover things we knew before we were born.

While painting Samain, Carrington struggled with the difficulty of capturing the shifting light of dusk. The moody, muted grey, tinged by bluish-green moonshine, appears at first as a near monochrome then moves a bit awkwardly through tonal modulation. The gloom is shot with rare touches of orange incandescence. The colors are restrained and alchemical—white is associated with purification and the production of silver; black with putrefaction. Grey admixtures predominate. Spare touches of red refer to physical matter.

Compositionally, three vignettes vie for the attention. Separate triangles are formed by birds, by cats, by sylphs or by white lozenges. The most dominant triangle is formed by three roughly rhyming forms: a kite aloft, an empty white shell of another kite afoot, and the similarly-shaped head of an elegant creature to the far right. The vectors trace a shifting set of magical coordinates. The whole composition is punctuated repeatedly by curved slivers shaped like tiny crescent moons. The gaze is made to flit around this de-centered space with some urgency. In a phrase that seems precisely right, Edward James described Carrington’s painting as the “vertiginous sublime.”

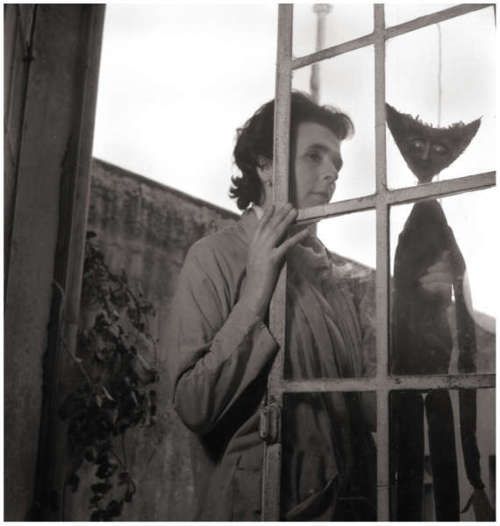

The tall, slender creature wears a furry, owl-feathered mantle and gently holds what might be an invisible egg. Floating just above her bent wrist is a floral burst. She has delicately tapered, clawlike hands, not unlike those we imagine for Juniper. Her opalescent head takes the mutable form that appears often in Carrington’s painting. It appears in doll form, too, in the photograph taken of Carrington by Kati Horna in 1960. The shape is a manta ray, perhaps, or a medieval cowl or wimple, a cat, the horns of Hathor, a moon, or a moth. Inhuman, unblinking pale pink eyes bulge. Her gaze is riveting, eerie and inscrutable. It beckons across an impossible breech. Just behind her stands a shawled crone like a whiskered walnut wearing a wildflower crown. Her gaze is cast like a spell upon the viewer as well. A white dove perches on her folded hands. The bird keeps company with a black crow and a plain, plump, earthbound hen.

A short wall demarcates a space to which the manta ray woman alone is privy. Within it sits a well-rounded pale blue egg, the alchemical egg that holds all potential within it as a muddle of solar and lunar, female and male, sulphur and mercury, matter and spirit.

Beside the wall, barely visible to those who don’t know to look for it, is an impossibly small door, granting access to the earthen mound inhabited by the diaphanous Sidhe—wispy, white, shape-shifting fairies from Celtic mythology that populated Carrington’s childhood reveries. The artist seems to have set herself the task of painting figures of blown glass, light as breath. They hover above ground, holding the ribbons of the kite that has caught the wind. It is also an airborne chrysalis. Inside this tissue envelope lurks a weird, black bat with a head like a pink moth undergoing its mysterious transformation. Two tawny spotted wild cats dance around this group; a third feline stands guard over a deflated chrysalis, dross that has been shed and cast off. Attempts at flight are precarious.

Here and there, the drawing is gossamer, picked out in glimmering silver. Overall the brushwork is thin and wispy, aimed at transparency. The painting seems to remain unfinished, still emergent from the active unconscious particular to Leonora Carrington. She registers the unseen spirits’ tentative attempts at becoming visible.

In L’art magique (1957), Andre Breton—an admirer of Carrington— enumerated Hieronymus Bosch’s earthly delights. The passage seems especially fitting of Carrington’s aspirations for Samain’s spirits as they become painting: This is the desire of the inhabitants of the Garden…I would like to have wings, a shell, bark; breathe smoke, have an elephant’s trunk, twist my body, be divided into many parts, be in everything, emanate like an aroma, develop like a plant, pour like water, vibrate like sound, shine like light, curl up under all forms, penetrate each atom… Painting was the medium by which Carrington extended vision toward the visionary. The spirits pushed back at this membrane, and on enchanted occasion, managed to pierce it. The painter grappled with the processes of transmutation and sublimation, trying to get beyond the five senses that weigh heavy on the page and burden readers, like Jumart and Drusille, with all-too-human bodies.