Category: 2000s

Stuff I Didn’t Buy #1

As you may have gathered already from reading this blog, I buy a lot of things at thrift stores. But, conversely, I also don’t buy a lot of things at thrift stores. My Dad and I usually do a thrift store run three or four times a week and it’s rare that I buy something interesting enough to write about on the blog. Many times I just come back with a book or two. Stumbling across something interesting enough to write about on the blog is an uncommon and happy occasion.

Other times though, I’ll see something that was interesting but that I decided for various reasons not to buy, Recently I decided to start documenting these things with my iPhone. Keep in mind that taking photos of items in thrift stores is not easy. I don’t want to draw too much attention to myself and often the lighting is very bad. These are not pictures that are up to normal Electric Thrift levels of clarity and composition.

This Bang & Olufsen Beogram 2400 turntable was a real surprise to find nestled within the serpentine labyrinth that is the Abbey Ann’s off of Tallmadge Circle. You can often find stereo equipment at that Abbey Ann’s but this was a cut above their usual offerings.

What this had going for it was that is a striking European early-1970s design. It was in the original box, including the cartridge, the Styrofoam packing material and the instructions. I adore the look of European electronics so this sort of thing is right up my alley.

There were two problems here. First, I think the price was a bit steep, though Abbey Ann’s is known to negotiate quite a bit. The second problem was that all of the glue on this thing had decided to dry up and much of the trim was coming off. It’s a bit hard to see in this photo but the wood-grain on the front was just hanging off. The little metal plate on the top of the end of the tone arm was coming off as well. The dust cover was getting stuck on something and would not close correctly.

I think if this has been one of B&O’s linear tracking Beograms I would have bought it in this condition. However, I’m already backed up on conventional turntables and this B&O looked like it was going to be trouble so I took these photos and moved on.

A few weeks later this 1980s JVC boombox showed up at that same Abbey Ann’s

This tugged at my heartstrings a bit because my Dad had a similar (probably slightly more recent, because it was black) JVC boombox in the late 1980s/early 1990s. I fondly remember making recordings with my brother using the built in microphone and tape recorder. My Dad had originally bought that JVC boombox because it got shortwave, like this one.

Despite all of the 80s electronics I buy, I haven’t yet gotten into boomboxes. I think I’m mainly waiting for one that’s in nice condition and fully functional.

Any time I’m looking at something with a tape player I’m worried about the condition of the mechanism. There are so many mechanical parts, including belts, that can deteriorate. I remembered that eventually the tape mechanism in my Dad’s 80s JVC boombox broke and I wasn’t really in the mood to spend even $10-$15 to find out if this boombox had any of the myriad of problems that tape decks can develop.

Those tape issues were also the first thing I thought of when I saw this Ampex reel-to-reel tape deck that showed up at the State Road Goodwill in Cuyahoga Falls.

I’ve wanted a reel-to-reel for a while now and this one is gorgeous in a mid-1970s silver and wood-grain way.

There were three problems here. The first is that reel-to-reels are notoriously troublesome. I believe one of the more notable moments of my Dad’s thrift store shopping career was when a reel-to-reel he purchased started smoking when he brought it home and turned it on.

The second problem was that while this is a great looking item it lacks two features I want to see in a reel-to-reel: Four channel output and some sort of exotic noise reduction like Dolby A or DBX. To me, the appeal of a reel-to-reel should be it’s exoticism compared to the common cassette deck and having fancy noise reduction should be part of the fun.

The third problem was that Goodwill wanted $50 for this thing. Sometimes I really question the pricing of some of this stuff I’ve seen at thrift stores lately. Asking $50 for something that’s for all intents not tested and sold “as-is” is not cool.

Coin collectors have a pricing theory that works like this: The price of a coin starts with the worth of the metal (copper, silver, gold, etc) and then you add a “numismatic premium” for the rarity of the coin and the condition of the coin.

I like to think that electronics at thrift stores should work in the opposite way. You start with what a sort of idea of what the thing should be worth and then subtract a “broken-ness risk premium” for the possibility that the thing is incomplete or broken.

$50 is a fair price to pay for a fully operational, totally complete (minus instructions and packaging) reel-to-reel. But it fails to take into account my risk in buying a potentially broken item.

This Memorex S-VHS deck from the same State Road Goodwill was the first S-VHS deck I has ever seen at a thrift store.

It was in pretty bad shape and my same concern with the tape mechanisms on the boombox and the reel-too-reel applied here as well.

There was also a front panel door missing. This looked like a lot more trouble than it was worth, whatever price they had on it.

Completeness is also a common reason I don’t buy some things.

This strange thing was at the Village Thrift on State Road a few months ago. I didn’t know what it was at first. Maybe some sort of TV?

When I turned it around and read the label things became clear.

This was some sort of pen-based tablet PC input device, like a poor man’s Wacom Cintiq.

I have learned from an experience with a Wacom Intuos (which I someday may write about) that you should never buy a pen-based tablet of any type without the pen because finding a suitable pen can be very expensive.

Completeness was also the reason I didn’t buy this Sony Mavica camera.

Comparatively early digital cameras are an area I’ve wanted to start collecting, so I was happy to see this Mavica show up at the Midway Plaza Goodwill. Unfortunately, the very proprietary looking battery (Sony, natch) was missing. I looked for a place where I could at least plug in an AC adapter. Then, I realized that there was this notch cut out of the area around the battery door with a little spring loaded door. it seems like rather than having an AC adapter this model had a thing that went into the battery compartment with a cord coming out of it (hence the little spring-loaded door) that acted as the AC adapter. Another piece of proprietary crap I would have to pay shipping for on eBay. Not worth it.

A Meditation on Racing Videogames

I’ve been on a videogame kick recently, so I ask if you will indulge me once again. The post on the Saturn, and my memories of Daytona USA and Wipeout specifically, stirred my thoughts about the racing game genre.

I own a few racing videogames.

It hadn’t actually occurred to me quite how many racing games I own until I tried to gather most of them in one place to get this picture. I also have several groups of games not shown here:

- A whole era of PC racing games from 1997-2005 or so like Rally Trophy, Motorhead, Rallisport Challenege, Colin McRae 3, and others I don’t have the boxes for at my apartment.

- A whole group of PC racing games like Midtown Madness that I just have in jewel cases from thrift stores.

- More recent purchases like Dirt 2, Blur, Fuel, and Grid 2 that I only own digitally.

I’m not really a big car guy or even someone who really enjoys driving in real life. It’s not really the cars that draw me into racing games.

I think what it comes down to is that I love playing videogames but I hate the “instant death” mechanic in most types of games.

That is to say that if Mario falls down a hole, he’s dead and you have to go back to the start of the level. If a Cyber Demon’s rocket hits Doom Guy he’s dead and you go back to the start to the level. In the vast majority of games the punishment for failure is that you the player are ripped away from whatever you’re doing and you lose progress in some way.

Racing games are in many ways the opposite of this. If you go off the road or hit a wall generally you lose time and you’ll probably not win the race, but the the priority is to politely get you going on your way again. Even in games like San Francisco Rush, where you can hit a wall and explode, you are quickly thrust back into the race somewhere further down the track. It’s like if you spilled a glass of water at a nice restaurant and the waiter quickly comes over to mop it up and replace your drink. You and he both know you just did a silly thing but he wants you back enjoying yourself as soon as possible.

That does not mean that these games are “soft”; it’s just that they don’t believe that constantly slapping you across the face is good value for money.

I mentioned in the Sega Saturn post that I don’t tend to like 2D games. The vast majority of racing games operate from an inherently 3D perspective that places the camera either behind the car or on the car’s bumper. In the pre-3D era there were attempts to do racing games with 3D-ish perspectives using 2D graphics, and I own a few such as Pole Position II, and Outrun.

It was difficult for 2D games to draw a convincing curving road so these games tend to make the player avoid traffic rather than attempt to portray realistic driving.

Racing games as we know them today trace their ancestry back to arcade games like Namco’s Winning Run (1988) and Sega’s Virtua Racing (1992) that were among the first to use 3D graphics and be able to draw a road in a more realistic way.

When consoles started using 3D graphics a nice looking racing game was a surefire way for console makers to show off their technology. A nicely rendered car on some nicely rendered road with some glittering buildings behind it is much less likely to trigger the uncanny valley than a rendering of a human. I think we can all agree that games like Gran Turismo 5 have come closer to real looking car paint than any game has come to real looking human skin.

Throughout the 1990s racing games exploded into several distinct sub-genres:

Arcade style games are the direct descendants of Virtua Racing and Winning Run, which is where the sub-genre derives it’s name. These days, these games are seldom released in arcades. Arcade-style racing games are not expected to have realistic handling but instead have handling designed for fun more than thought. The brake peddle/button in many of these games is a mere formality. Early on in the 3D racing era companies like Namco and Sega added drift mechanics to their games where you could toss the car around corners at speed rather than braking realistically. Arcade racers like Daytona USA and Ridge Racer were very popular in the 32-bit era (Playstation, N64, Saturn) but the arrival of mainstream simulation racers drew attention away from these games in the late 1990s and early 2000s (which sadly meant many people overlooked the fantastic Ridge Racer Type 4). The arrival of Burnout 3: Takedown in 2004 reinvigorated the sub-genre by allowing you to knock other cars off the road rather than just trying to pass them.

Beginning with games like Driver, free-roaming racing games left the predefined track and let the player roam though cities and other environments. Crazy Taxi (1999) combined the arcade-style with free-roaming forcing the player to memorize routes through a large city in order to pick up and deliver fares. Test Drive Unlimited (2006) allowed players to drive around the whole island of Oahu. Burnout Paradise (2008) put the frantic Burnout style of arcade racing into an open city.

Kart racing games (named after Super Mario Kart) tend to have arcade style handling but in most cases have a recognized character like Mario or Sonic sitting in a tiny car. In Kart racers it’s expected that you can driver over or through symbols/objects on the track to pick up weapons, which you can use to slow down or otherwise befuddle opponents, or drive over speed pads which give you a nitro boost. In Kart games the strategy of using the weapons is as important or more important than your ability to guide the car. The Kart racing genre is 90% Mario Kart and 10% everyone else. If you’ve never played them, I recommend Sega’s two recent kart racing games: Sonic and Sega All-Stars Racing and it’s sequel Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed.

Futuristic racing games are a close cousin to Kart racers because they also allow you to pick up weapons on the track to hurt opponents. Generally futuristic racing games have more realistic graphics than Kart games and a cyberpunk/dystopian visual atmosphere accompanied by a electronica soundtrack. Wipeout is the patron saint of futuristic racing games.

Simulation racing games seek to exactly simulate the handling characteristics of a real car. Games like the Gran Turismo series, F355 Challenge and the famous Grand Prix Legends take great pride in the way they have exactly replicated real tracks and the handling of real cars on those tracks. There are actually people who have become real drivers after learning in these games. Gran Turismo popularized the idea that mainstream simulation games should have dozens of realistically rendered sports cars that need to be collected by the player. In Gran Turismo the incentive to race is to collect cars. Today Microsoft’s Forza series and Sony’s Gran Turismo are the kings of mainstream simulation racing.

There is another sub-genre that doesn’t really have an established name that is somewhere between the simulation and arcade styles of handling. I like to call it sim-arcade. The Dreamcast’s Metropolis Street Racer is an early example of this type of game. Codemasters’ Grid and Grid 2 are more recent examples. In sim-arcade racing games you still have to think about your line and braking correctly for the turns but it’s not quite as anal about it as the simulation games. A lot of people confuse this style for the arcade-style because they assume that any game that is not full-on simulation must be arcade style. A good rule of thumb is that if you don’t have to use the brake except to trigger a drift, you’re playing an arcade style racing game. If you have to actually brake for a turn and you’re not playing a sim, it’s probably this sim-arcade style. There can be a arrogance among simulation players that more realistic games are better but I tend to really enjoy the sim-arcade style.

Descending from 1995’s Sega Rally Championship rally racing games are intended to replicate rally driving on off-road surfaces. The actual sport of rally racing takes place as a series of time trials cars drive individually but some of these games allow players to drive against other cars as well. The Sega Rally games take a more arcade approach to handling while Codemasters’ Colin McRae Rally and Dirt games take a more balanced approach somewhere between sim and arcade. Today Dirt 3 and Dirt Showdown basically own this genre.

I wish I could say that the current state of the racing game genre is as rich and vibrant as it was in the past. There is a crunch going on in the videogame industry where game budgets are increasing faster than sales and the large videogame publishers increasingly feel they can’t take risks about what their customers will buy. I suspect that racing games have become labeled risky niche products while military-style first person shooters like Call of Duty and third person action games like Assassin’s Creed are commanding big budget development dollars.

In 2010 when Disney and Activision put out well-advertised arcade-style racing games (Split/Second and Blur, respectively) sales were abysmal and the excellent studios behind those games (Black Rock and Bizarre Creations, respectively) were closed. The fact that both games looked superficially similar, which confused potential customers and the fact that both games were released in the same week up against the blockbuster hit Red Dead Redemption does not seem to have entered any executives minds as to why sales were poor. A chill seemed to descend upon the arcade racing subgenre after that with only Electronic Arts carrying the torch after that with their Need for Speed games.

The videogame playing public, it seems, are sick of just going around in circles and developers can’t seem to figure out what to do next.

Lately developers have been keen to invent shockingly dumb and bizarre plots to justify racing games:

- In Split/Second the game is supposed to be some massive reality TV show where the producers have conveniently rigged and entire abandoned city to explode while daredevils race through it in order to provide interesting television.

- In Driver: San Francisco the main character is actually having a coma dream where he believes he can jump into the consciousnesses of drivers in San Francisco and complete tasks in their cars. I wish I was making this up.

Racing games, like puzzle games, are probably better off without plots.

Still, I think racing games need a kick in the pants in order to stay a relevant mainstream genre.

In other genres, like side-scrolling shooters and platformers the influence of indie developers are helping those genres find the souls they had lost under the weight of big budget design by committee. I’m hoping something similar happens with racing games. I am extremely enthusiastic about the 90s Arcade Racer game on Kickstarter that is a love letter to the arcade racing games that Sega made in the late 1990s (Super GT/SCUD Race and Daytona USA 2) that they were too stubborn to release on consoles.

Odds and Ends #2

I mentioned last week how much I loved going to the library as a child. These days rather than going to the library I tend to buy used books from thrift stores and used book stores.

I used to look at thrift store book sections with disdain because they were mostly filled with romance novels, out-of-date political books, self-help guides from the 70s, and other forms of useless drivel.

But, what I came to realize is that there’s always a diamond in the rough and considering how much rough thrift stores tend to have, the rate of finding diamonds is pretty high. The beauty of it is that because these books tend to be so cheap you can really indulge your curiosity without feeling like you’re throwing away money.

Sometimes I’ll buy a book because I know nothing about the subject matter.

Ekiben: The Art of the Japanese Box Lunch

I was at the Goodwill on State Road in Cuyahoga Falls recently when I found this 1989 coffee table book about Ekiben, the Japanese tradition of creating special Bento box lunches for sale at train stations so that people can eat them on the trains.

I can’t imagine a similar book about American airline food, can you?

Other times I will buy a book because I am very familiar with the subject matter or I’m collecting books on a specific subject. Ever since my parents bought me the Encyclopedia of Soviet Spacecraft as a child I’ve been interested in collecting books about spaceflight, including books by or about astronauts.

We Have Capture: Tom Stafford and the Space Race

I think I found this copy of We Have Capture, the autobiography of astronaut Tom Stafford (co-written with space writer Michael Cassutt) at the Waterloo Road Goodwill in Akron.

Among the Apollo astronauts Tom Stafford is somewhat forgotten because he didn’t walk on the Moon and until I read We Have Capture I didn’t realize how much of an impact Stafford had made. After flying on Gemini 6 and Gemini 9 , Stafford commanded the Apollo 10 mission, which was a dress rehearsal for Apollo 11. He and Gene Cernan descended in the Lunar Module to about 47,000 feet above the Moon’s surface before testing the Lunar Module’s ability to abort during landing.

However, the most interesting part of Stafford’s career came after the Moon landings. In 1971 was sent as a US representative to the funeral for the cosmonauts who died on the Soyuz 11 flight. Later he would command the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), the flight that is depicted in the jacket image. ASTP is somewhat forgotten today but in a historic moment of the Cold War in 1975 the final US Apollo flight docked with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in order to demonstrate international cooperation. What’s fascinating is that in the 25 years after ASTP Stafford continued to act as an adviser for NASA and helped to shepherd the Shuttle-Mir flights and the transformation of the failed Space Station Freedom project into the joint US-Russian-European-Japanese International Space Station project. In many ways the most interesting parts of the book have to do with Stafford’s techno-bureaucrat functions on that ground more than what he did in space.

Incidentally, I hope someday a space writer like Michael Cassutt, Andrew Chaikin or Dwayne Day writes a book-length history of the origins of the International Space Station (ISS). From what I understand there were some unique political, diplomatic, and engineering challenges that were overcome to create the ISS.

The best writer to tell that story may be William Burrows, author of books including Deep Black and Exploring Space.

Exploring Space: Voyages in the Solar System and Beyond

I found this copy of Exploring Space at the Waterloo Road Goodwill in Akron. This is a funny book because to look at the cover this looks like your standard “spaceflight is so great” kind of hagiography that’s common among books about spaceflight. In Exploring Space from 1990, Burrows actually takes a more critical approach.

I don’t think Burrows dislikes us spending money on exploring space. Rather, he’s unhappy, perhaps even disgusted with the way we’ve gone about doing it. The history of spaceflight is rife with good ideas that were poorly executed repeatedly before the engineers got them right (JPL’s early flights in the Pioneer, Mariner, Ranger, and Surveyor series) , good ideas that we spent way too much money on before they were finally executed right (Viking and Voyager) and questionable ideas that were forced to be realized because of political pressure (like the Space Shuttle). The bizarre way that we fund spaceflight through political kabuki lends itself to these kinds of costly messes. I suspect that if Burrows were writing Exploring Space today he would be more sympathetic to NASA’s cost controlled Discovery program, very unhappy with the James Webb Space Telescope, and seething with rage about the forthcoming SLS launch vehicle.

An interesting example of when spaceflight vision and reality collide is well illustrated by…

Challenge of the Stars: A Forecast of the Future Exploration of the Universe

This thin coffee-table sized volume is another book I found at the Waterloo Road Goodwill. I remember that I spotted it right after one of the book’s authors, the English astronomer and television presenter Patrick Moore, had died late last year.

Much like The Compact Disc Book, I mentioned last week, the fun of Challenge of the Stars is seeing if what they predicted would occur that has occurred and what has not occurred. One thing they got right was the “Grand Tour” of the solar system that became the Voyager 1 and 2 probes.

This stunning illustration of a proposed docking between a Soviet Soyuz and the US’s Skylab space station (note the Apollo CSM waiting in the distance). This idea was turned down in favor of the Apollo-Soyuz Test project flight that Tom Stafford flew.

What really caught my eye though, was the section on space stations and a manned Mars landing.

On the bottom left is one of the earlier proposals for the Space Shuttle. Rather than the External Tank and Solid Rocket Boosters we bacame so fami,iar with, this earlier proposal used a liquid-fueled booster that would fly back to the launch site and land rather than being discarded like the External Tank.

The real prize though, is the photo on the opposite page. Here’s a closer view.

Other than the fact that this is a beautiful piece of art, there’s quite a bit of political history attached to this image. This was produced for a study that Von Braun’s group at Marshall Spaceflight Center conducted in 1969 about what to do after Apollo.

That blunt-nosed craft in the middle of the image with the three cylinders with the USA insignia on them are Von Braun’s idea for a manned-Mars exploration ship. The three USA-labeled cylinders are actually nuclear powered rockets. Here a space shuttle is delivering a fuel shipment to the craft while it’s being assembled in orbit nearby a space station. What you’re seeing envisioned here would have taken dozens of Saturn V launches to get into orbit.

On a later page is an illustration of what the Mars Excursion Module, Von Braun’s Mars lander, would have looked like sitting on Mars. Note that it’s basically a giant-sized Apollo command module.

The excellent False Steps blog goes into more detail but essentially this outrageously expensive proposal was laughed out of the room in Washington. One of the reasons we got the Space Shuttle after Apollo was that the Space Shuttle was seen as more cost effective than Apollo, and into this atmosphere NASA’s spacecraft designers at Marshall were tilting at windmills rather than proposing a more cost-effective alternative to the Shuttle.

It’s fascinating to imagine what might have been though, had Von Braun’s Mars mission proposal been accepted by Nixon. In fact…

Voyage

Voyage, by Stephen Baxter is a science fiction novel that explores an alternate history where a version of Von Braun’s proposal was actually carried out and the United States landed on Mars in 1986.

I believe I found this paperback at Last Exit Books in Kent.

Voyage is a real treat for spaceflight fans because it goes into immense detail about the trials and tribulations of the political squabbling, engineering feats, test flight mishaps, and other nerd candy that lead up to the Mars landing. Clearly Baxter studied the various Mars mission proposals from the late-1960s and early 1970s carefully because many of the details from Von Braun’s plan, like upgrade versions of the Saturn V and the NERVA nuclear rocket project make their way into Voyage. He also takes cues from real life as well. For example, rather than the Challenger disaster, a gruesome mishap occurs with on a NERVA rocket test flight. Rather than the ASTP mission flying, the Soviets are invited to a US Skylab-style station orbiting the Moon. If you’re a space nerd at all, Voyage is going to be right up your alley.

Sometimes I stumble onto neat space memorabilia in unexpected places.

Atlas V AV-003 Interactive DVD

I was at the Kent/Ravenna Goodwill a few weeks ago browsing at the DVDs and suddenly I see a DVD that says Atlas V AV-003 on the side.

I expect to see Atlas V rocket serial numbers the on the NASASpaceflight.com forums, not on something at Goodwill.

The Atlas V is a launch vehicle originally developed by Lockheed Martin and currently built and operated by the United Launch Alliance. You might remember the original Atlas rocket that began as an ICBM in the 1950s, flew astronauts during the Mercury program in the early 1960s, and became a workhorse for launching satellites and space probes well into the 1990s. Since then, the Atlas name has become a sort of brand name for the Atlas rocket family. The current Atlas V has design heritage that goes back to the Titan and Atlas-Centaur rockets and uses a first stage booster engine built by the Russians.

This is the Atlas V AV-003 Interactive DVD. AV-003 refers to the serial number of the rocket, so this DVD documents the launch of the third Atlas V in 2003.

At first I was a bit disappointed in this DVD because it seemed to be full of standard marketing video drivel and over-produced launch video crud. That is until I found the menu where they let you watch every camera that was covering the launch. There are the cameras you expect to see: cameras on the pad and tracking cameras that track the rocket from afar.

But then there are cameras mounted on the first and second stages. I’ve seen these used on launch videos before, but I had never had the chance to just watch the raw footage with no commentary or editing.

Here is a view on the first stage looking downward as one of the solid rocket boosters separates.

And there it goes tumbling away.

This camera is looking upward as the payload fairing (aka the nose cone) separates after the rocket has gotten far enough out of the atmosphere that it can shed the weight of the fairing.

This is from the same camera looking upwards after the first stage has shut down and the second stage, a Centaur upper-stage, has started and speeds away from the dead booster.

I have no idea how a DVD like this made it’s way to the Kent Goodwill, but it made my day when I found it.

SNK NeoGeo Pocket Color

This is my NeoGeo Pocket Color (NGPC), a short-lived handheld videogame system that the somewhat esoteric Japanese company SNK sold from 1999-2001.

I believe I found it at Village Thrift sometime well after the system was discontinued in the United States in 2000.

Village Thrift has a good habit of taking a lot of items that go together, like a NGPC and several games, and putting them together in a clear plastic bag. I remember finding it at their showcase, rather than the electronics section.

I’m also not sure if the scratch on the screen was there when I bought it or if that happened later.

The games that were in that plastic bag along with the NGPC were:

Sonic The Hedgehog Pocket Adventure, a Sonic the Hedgehog platformer:

Bust-A-Move Pocket, an entry in the well-known puzzle game series that resembles Bejeweled:

Baseball Stars Color, a fairly straightforward baseball game:

Neo Dragon’s Wild, a collection of “casino” games:

Metal Slug 1st Mission, a portable version of SNK’s Rambo-like side scrolling platforming shooter:

And finally Metal Slug 2nd Mission, the sequel to Metal Slug 1st Mission:

Oddly enough, there were no fighting games in that lot because that’s what SNK was known for and what enthusiasts wanted the NGPC for.

There are several neat and interesting things about the NeoGeo Pocket Color hardware. The first is that it has this tiny spec sheet for the display written above the screen.

You know, in case you ever need to look up it’s pixel pitch.

The screen on the NGPC can be difficult to see in all but direct sunlight and it can also be a pain to photograph. So, if my screenshots look odd, that’s why.

The need for very bright light in order to see the colors well was a problem with a lot of the color portable systems of this time period. I fondly remember the uncomfortable position I had to sit in to play Tetris DX on my purple Game Boy Color while hunched below a reading light that was attached to my bed. Penny Arcade memorably poked fun of the difficult to see screen on the Game Boy Advance in 2001. The rise of back-lit screens like the one on my Game Boy Micro finally alleviated this problem.

The unfortunate thing is that when you see screenshots of games from the NGPC and Game Boy Color from emulators you realize what beautiful colors those games were putting out and how the hardware made them almost impossible to see.

The NGPC has a unique 8-way joypad located on the left side of the console. This was the system’s most memorable feature and one that people would be wishing for on other portable game systems for years afterword.

Unlike the control stick you might see on an XBox controller this is a digital control pad, rather than an analog one. However, because it can move in eight directions it’s easier to point in a diagonal direction than a conventional cross-shaped D-pad like you find on Nintendo systems. SNK specialized in 2D arcade games that had sophisticated joysticks so it’s no surprise to find something like this on their portable system. The joypad has a really solid feel and makes a lovely clicking sound as you move it around.

On the back the NGPC curiously has two battery covers. The system uses two AA batteries to power the system and one CR2032 button battery to backup memory to save games and settings.

If the CR2032 dies you get this lovely warning message when you turn off the console.

When you turn on the NGPC the boot screen has an attractive little animation accompanied by a cute little tune.

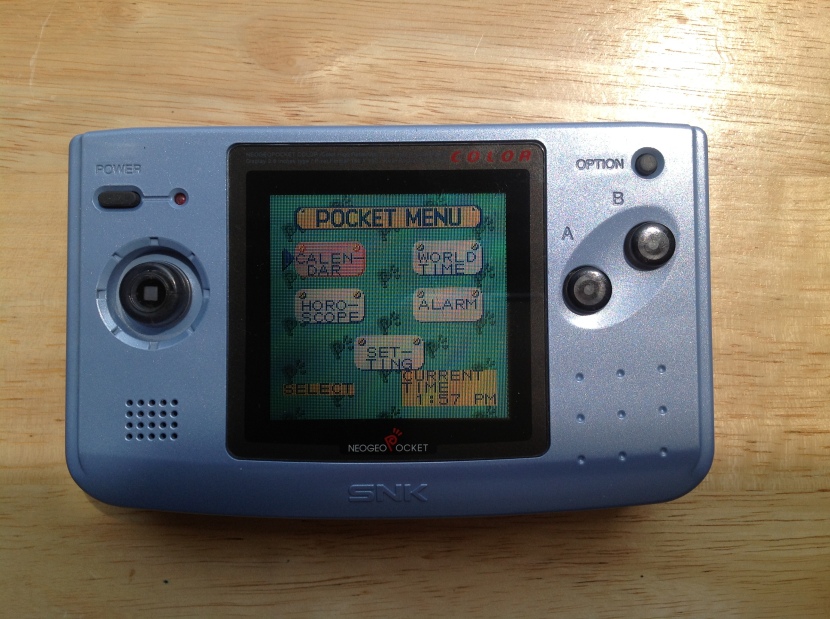

If you turn on the NGPC without a cartridge you get this menu screen that includes a calendar and (in silly Japanese fashion) a horoscope.

I can’t think of a videogame feature more utterly useless than a horoscope.

In order to explain the NeoGeo Pocket Color I have to tie together a few threads.

SNK is not what you would call a household name in the US but it was one of the titans of the Japanese arcade in the 1980s and 1990s. Their specialty was (and still is) was 2D fighting games. That is to say that the graphics are hand-drawn sprites that view the action from the side.

In 1990 SNK released the NeoGeo home console which for all intents and purposes was one of their arcade machines repackaged for home use. As you would expect it was outrageously expensive. The console itself (including a pack-in game) was $650 and games cost $200.

If you owned a Sega Genesis or a Nintendo SNES the NeoGeo must have seemed like some sort of mystical Shangri-La.

If you purchases a NeoGeo what you would have gotten for your obscene amount of money were perfect arcade games in the home. From the beginning of the home console market the fidelity of home console conversions of arcade games had been a constant problem. There were always compromises in animation, music, fluidity, and control sensitivity. Not so, if you were a NeoGeo owner. What you got was perfection.

But in the mid-1990s the market moved on to consoles such as the PlayStation and N64 that were built around 3D graphics. The arcades moved on too, and fighting games like the Tekken and Virtua Fighter series that were built on 3D graphics excited the public’s imagination.

SNK’s contemporaries like Capcom (whose Street Fighter series is one of the pillars of the 2D fighting genre) found ways to stay relevant by developing new series like Resident Evil while continuing their line of 2D fighting games. SNK didn’t and the NeoGeo became an expensive collector’s item.

Then, something possessed SNK to release a monochrome portable system called the NeoGeo Pocket in 1998 followed by the NeoGeo Pocket Color in 1999.

1999, when the NGPC came out, was a very strange time for portable videogames because it’s when the technological gap between the home consoles and portable consoles was at it’s peak. It wasn’t so much a technological gap as it was a chasm.

It’s funny how technology trends wax and wane over decades. Today, vast sums of R&D dollars are being spent on making components (especially CPUs and GPUs) for portable electronics faster and more power efficient. Intel’s new (Jone 2013) Haswell processors have marginal speed gains for desktop users but offer better battery life and less heat for mobile users. Across the industry from Apple to Samsung the effort is going into making better mobile devices.

Back in 1999, everything was different. Back then the money was being put into chips for devices like PCs and home game consoles that were plugged into the wall. We wanted faster devices and didn’t much care how much power they used or how much heat they put out.

In the home console market, the Dreamcast had just debuted, ushering in an era of more more refined 3D graphics that would lead to the PS2, XBox, and GameCube.

The Dreamcast was powered by a 32-bit Hitachi SH-4 RISC CPU and a PowerVR GPU that’s the direct ancestor of the GPU in today’s iPad and PS Vita.

Meanwhile in the portable realm the popular Game Boy Color was still based on an 8-bit CPU, technology that was solidly rooted in the game consoles of the 1980s. Very roughly this meant that the state-of-the-art home console was at least several hundred times more powerful than the leading portable console.

Battery life was the root cause of this gap. You could build a much more powerful portable system with a much more powerful CPU, much more RAM, and a higher resolution back-lit screen. But, it would have been heavy and had horrendous battery life. The marketplace thrashings that the Atari Lynx, the NEC TurboExpress, the Sega Game Gear, and the Sega Genesis Nomad received at the hands of the Game Boy throughout the 1990s were all clear proof of this reality.

Essentially those systems had tried to be to the Game Boy what the NeoGeo had been to the SNES and the Genesis, a far more powerful, far more expensive competitor. But, there was no place for that in the portable market.

The breakthroughs that would happen in the mid-2000s that allowed the revolution in portable computing devices simply had not occurred yet.

In 1999 the Game Boy Color sat at the sweet spot between battery life, weight/size, and cost. As a result, any serious competitor would have to have a comparable size, weight, cost, and battery life to the Game Boy Color and that precluded anything that was vastly more powerful. But it would also make it difficult for a serious competitor to differentiate itself from the Game Boy.

Technically, the NGPC was a 16-bit system and the Game Boy Color was just an 8-bit system but at these CPU speeds, with these amounts of RAM, and with these screens, the difference was negligible.

So the situation you had was that SNK must have felt that their background in 2D arcade games would be an asset in portable games, which were still totally dominated by 2D graphics even as the home consoles were putting out increasingly sophisticated 3D graphics. They probably also thought that as a company that specialized in fighting games they could build a portable game system suited to fighting games (with that gorgeous 8-way joypad) and exploit a market that Nintendo had ignored.

The problem was that 1998-1999 was an awful time for any company not named Nintendo to launch a handheld game console. From the earliest days of the Game Boy most of the best games had been essentially miniature versions of console games. The great games of the Game Boy from 1989 to 1998 include Super Mario Land 1 and 2, Metroid II, Legend of Zelda: Links’ Awakening, Kirby’s Dream Land, the Donkey Kong Land series and other games that basically would not have existed without their console counterparts.

Pokemon changed all of that in 1998 (in the US). Here was a game that had no console counterpart. Here was a game who’s popularity was strongly attached to being able to play the game against and with friends by connecting your Game Boys together. Here was a game that lent itself to consuming every available hour of a child’s day –on the school bus, on the playground, waiting at the doctor’s office, etc — like no game since Tetris.

NGPC had nothing comparable to Pokemon. At the time, the influence of SNK’s 2D arcade games was waning in American arcades so for the vast portion of the NGPC’s potential audience they had very little to offer. There were SNK enthusiasts who loved the NGPC and there were fighting game enthusiasts who loved the NGPC, but on the whole it didn’t make much headway in the American market. And that’s why mine ended up at a thrift store a few years later.

Nintendo Game Boy Micro

I had originally planned to put up a different post this week but some technical issues and the fact that I had a cold means that post will have to wait for some other week.

Today though, I’m going to bend the rules somewhat because this is an item that technically I didn’t buy at a thrift store but I did buy used.

This is my Nintendo Game Boy Micro which I purchased sometime in 2008 at The Exchange in Cuyahoga Falls.

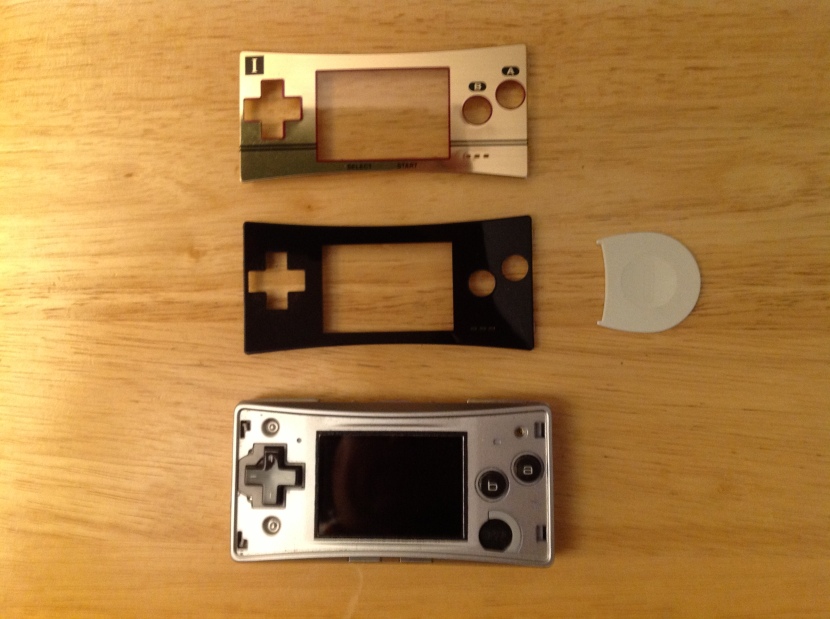

Released in 2005, the Game Boy Micro is a miniaturized Game Boy Advance that loses compatibility with original Game Boy and Game Boy Color games but gained a brilliant (if tiny) screen and a headphone jack that the Game Boy Advance SP oddly lacked..

The Game Boy Micro is, in my opinion, the sexiest piece of videogame hardware ever created. It’s so tiny and jewel-like while at the same time so utterly minimalistic that it just looks better than anything else Nintendo, or perhaps anyone making portable game systems has ever made. It’s not surprising looking at it’s brushed metal construction that the Micro was a contemporary of the iPod Mini and was widely believed to be Nintendo’s bid to capture customers looking for another stylish portable gizmo. It’s so beautiful that you almost feel bad inserting a cartridge because it clashes with the color scheme.

Practially the Micro can be a bit tough to hold for any long period of time. The tiny size (it only measures 50×101×17.2 mm) means that in order to have your index fingers on the shoulder buttons and your thumbs on the D-pad and a+b buttons there’s a good chance you’ll have to hold your hands at an uncomfortable angle. I have pretty small hands and holding the Micro is just about at the edge of discomfort for me. Additionally, while the screen is bright and the colors are well defined the screen is still just 2 inches wide.

The Micro’s party piece is that it’s faceplates are removable so you can change the appearance of the system by changing faceplates with a plastic tool.

Here are the three faceplates I own, along with the plastic tool:

I believe that when I bought the Micro used it was wearing the obnoxious red/orange faceplate. Back in 2008 you could still order new faceplates from Nintendo’s parts site so I bought the stylish black plate and the nostalgic Famicom faceplate. Sadly today they only offer replacement AC-adaptors.

The plastic tool inserts into these two holes on the side of the Micro with the D-pad (on either side of the screw):

Micro owner Pro-tip: Always insert new faceplates so that you hook in the side with the longer hooks near the a+b buttons first.

This is what the Micro looks like without any faceplate mounted:

One practical advantage to the faceplates is that they act as hard screen protectors, but really they just look bitch’n cool.

However, the real reason I want to talk about the Game Boy Micro is it’s historical significance to Nintendo. The Game Boy Micro is the last Game Boy as well as the last 2D gaming system from Nintendo.

Now, I would not be shocked if some day Nintendo reuses the Game Boy name but suffice to say Nintendo started selling a line of cartridge-based portable game systems with four face buttons (labeled a, b, start, and select), a D-pad, and one screen in 1989 with the original Game Boy and created a succession of systems with those attributes that ended in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro.

Following the Game Boy Micro Nintendo retired the Game Boy name and has produced the Nintendo DS line of cartridge-based portable game systems with two screens, one of which is a stylus-based resistive touchscreen, six face buttons (labeled a, b, x, y, start, and select), and (at least) a D-pad.

More importantly though, the Game Boy Micro was the last Nintendo system of any kind that was primarily built to play games based on 2D, sprite-based graphics rather than today’s 3D, polygon-based graphics.

This means that the Game Boy Micro was Nintendo’s final love letter to the era when it dominated the videogame world with the NES/Famicom and SuperNES/Super Famicom. There’s no coincidence to the fact that the Micro itself resembles and NES/Famicom controller.

From the release of the Famicom in 1983 to December 3rd, 1994 (when Sony released the Playstation in Japan) Nintendo was undoubtedly the single most important force in the console videogame world. Surely Sega played some part as well, but while they could on occasion be Nintendo’s equal they were never Nintendo’s superior.

But, as the world marveled at the Playstation and the rise of 3D graphics, Nintendo’s influence crested and then began to wane. Today they are an important part of the industry, but they have never again become undisputed champion.

However, in the portable gaming arena, Nintendo was still the undisputed champion (and still is today, as tough as it is for this PSP and Vita owner to admit). When Nintendo decided to replace the Game Boy Color in 2001 it returned to a 2D-based system and created the Game Boy Advance. An era of 2D nostalgia reigned with the GBA finding itself home to classics of the 16-bit era re-released as GBA games and new 2D classics that heavily drew inspiration from SNES games.

So, when Nintendo said it’s final goodbye in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro it was really closing the door on the era of 2D gaming it had dominated from 1983 to 2005. In that way the Micro is comparable to the last tube-based Zenith Transoceanic or the last piston-engined Grumman fighter aircraft. When a great company wants to say goodbye to one of it’s great products they will often create something fantastic as a last hurrah and that is clearly what Nintendo did with the Game Boy Micro.