I’ve given this post the title “A Family in Service” in recognition of the way the war affected both American serviceman Albert Rosenblum and his family as a whole.

Like many families during World War II, Al’s parents had more than one son serving in the military.

Al was married when he went overseas in 1942. A close network of relatives provided support for his wife Rose and for his parents while he was at war and a prisoner.

After the war’s end, Al stayed in the service, and Rose and their son Alan lived with him when he was stationed in occupied Japan. Al also served in the Korean War. He enlisted in 1929 and served to 1938. He then rejoined his old unit in 1939 and served until 1953.

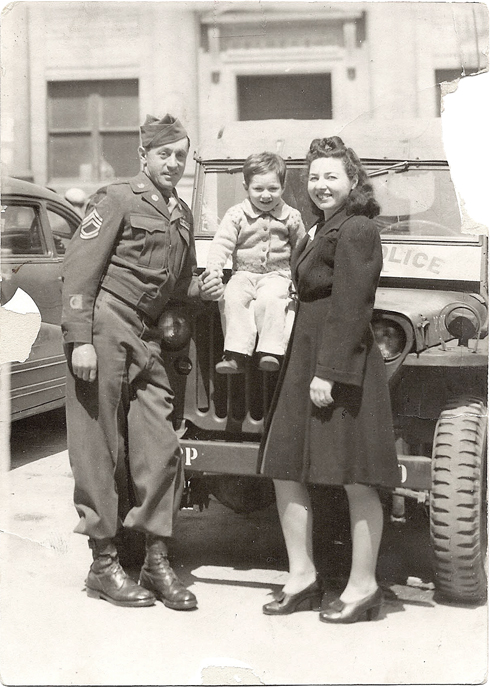

Staff Sergeant Albert Rosenblum with son Alan and wife Rose in Japan, 1947.

Here is Alan’s story of his dad’s service:

My father, Staff Sergeant Albert Rosenblum, joined the U.S. Army during the Great Depression of the 1930’s. He served at Fort Hamilton, New York, Schofield Barracks in the Territory of Hawaii, and Fort Douglas, Utah. During that period he twice encountered President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Once when F.D.R. made an inspection tour of Hawaii military bases and later at the dedication of The Hoover (Boulder) Dam, where my father was a member of the Honor Guard.

Photos Al took of Franklin Delano Roosevelt when the president was on Hawaiian inspection tour, 1934.

Al (on left) at rifle practice in Hawaii, 1934.

Al and Rose not long before Al was sent to North Africa, 1942.

After leaving the Army, Dad opened a small business in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. As rumblings of war grew, he re-enlisted with his old outfit, the 18th Infantry Regiment, in New York. They departed overseas on troop ships in August of 1942, and trained in Scotland until October, when they shipped out to North Africa.

The 18th Infantry went ashore east of Oran, Algeria in November of 1942. The next March, part of the 18th Infantry maneuvered into position at El Guettar, Tunisia. The 18th Infantry was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division—called the Big Red One—and Al said the soldiers used to joke, “If you’re going to be one, be a Big Red One.” He found himself in the middle of history about to unfold. He was in Patton’s Army, with F.D.R.’s son Brigadier General Ted Roosevelt commanding the sister regiments of the 16th and the 18th Infantries. They were facing Rommel’s “Afrika Corps.”

On the night of March 22nd, my father’s outfit was attacked by German panzers and infantry. Half of his platoon were killed and the rest were taken prisoner. Even though he was severely wounded, he had the presence of mind to discard his dog tags after capture. Dog tags were stamped with the soldier’s religion and the “H” on his, for Hebrew, could have had dire consequences.

He was flown in a German transport plane to Italy. During the flight, the transport was attacked by Allied fighter planes and he was wounded yet a second time, en route to Naples Airfield. He was then transferred to Italian Prisoner of War Hospital Camp 206 at Nocera, near Naples, where his wounds were treated. He would later say that the Italian doctors cared for him well and probably saved his life.

Once I asked him what it was like over there and, not wanting to frighten a ten-year-old, he said, “You would shoot your rifle and then reach over and pick an orange.”

His capture was hard on the family. They were used to his mail being delayed for several weeks and the censorship, but then my mother received a Western Union telegram on April 21, 1943 stating, “Regret that your husband …. reported missing in action (MIA) …. North Africa area since March 24th,” she didn’t know what to think.

She was living on her parents’ farm in White Lake, New York, and would take solace by working in the fields to ease her heart and mind about Al’s situation. Her two farmer brothers and her high school-aged sister were at hand for comfort and support, and a younger sister working in New York City visited whenever she could.

Rose on the family farm in White Lake, New York, 1943.

Dad’s family in Columbus was worried also. Two of his brothers were doctors in the Army Medical Corps, Dr. Max and Dr. Earl, who was a flight surgeon in the 8th Army Air Corps in England. They tried to use their connections and influence to find any information on Al’s whereabouts—but they had no success. Al’s other brother and sister also offered a support network to the family.

Al’s mother posted three stars in her living room window to honor her three sons in the military. She once said that she knew something had happened to her second son, Al, because the middle star “faded” in the sunlight at the time he was captured.

Dad was transferred to POW Campo 59 in Servigliano, Italy. Conditions at the camp were spartan, especially the lack of an adequate food supply. One of the prisoners’ main topics of conversation was food. They spoke of their mothers or wives and their home cooking, favorite foods and favorite restaurants, and what they would first eat upon returning home. They thought, dreamed, and hallucinated about food.

The Red Cross was a lifesaver. On occasion they would send food parcels to the camp, and these supplemented the meager meals—except for what was stolen by the guards.

At times the Red Cross was also able to send messages and forward packages from home to the POWs. Dad became very popular in Camp 59 when my mom used her food ration allowance for a salami, which she sent to him through the Red Cross. He said that men from other billets would come over to “chat” and enjoy a taste of the salami.

In my adolescent naiveté, I once asked my Dad if he ever had pizza while he was in Italy. He said, “No pizza, but we had cooked pig’s blood and it tasted pretty good at the time.”

Dad and three other prisoners hatched an escape plan that involved much self-sacrifice. As hungry as they were, they saved and hid “luxury” items from the Red Cross parcels and bribed a guard. The guard left a gate unlocked and they escaped that night with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They evaded Italian and German patrols by traveling at night, trying to stay off the roads, resting during the day in ditches and thickets of shrubs and trees. It was a difficult trek in foreign enemy territory, none of them understanding the language, and with no food or weapons and no clear destination. They were most worried about German patrols, as the Germans would shoot first and ask questions later.

Eventually they ran into some locals who put them in touch with the partisans. For almost a year they lived and worked behind enemy lines with the Italian underground. Wearing civilian clothes and working on farms, the group also intercepted and burnt convoys carrying ammunition and war equipment through the area.

This period was particularly difficult for our families, because they had no contact with Dad, or knowledge of his situation or whereabouts.

Dad was eventually repatriated when American troops moved up the “boot” of Italy. He was sent by ship to Boston, where he was debriefed at length. The first inkling the families had of his safe return was from my mother’s 16-year-old sister, who was working part time as a telephone operator that summer. She handled a long distance call from the military to my mother at the farm and knew it must be important. When she got home—since operators weren’t allowed to listen in—she learned that Dad had landed in the U.S. and was on his way back.

After the War, Dad decided to continue his career in the Army. He served two years in occupied Japan with Mom and myself, and 18 months in the Korean War. After WW II, the government decided that because of Dad’s POW experience at Camp 59 he would be reassigned from infantry to military police—and so he became an MP. Indeed, during the Korean War he handled Chinese and North Korean POWs, along with his other duties.

After Dad was discharged from his first military service in the late 1930s, he opened a small business in Columbus selling paper, cardboard boxes and bags to groceries, butcher shops and other businesses.

Interestingly, in the mid 1950s, we received a letter addressed to Sgt. Albert Rosenblum, Columbus, USA. It was from the son of a family he stayed with while working with the underground after his escape. The son, whom Dad had taught to box, was now a young adult and thinking of immigrating to the U.S. He wondered if Dad would be a sponsor. We wrote back, but sadly received no reply.

Doctors could never remove all of the shrapnel Dad sustained at El Guettar, and he received a partial disability from the V.A. On occasion, pieces would work themselves out and he would find little bits of metal in bed, which served as a recurring reminder of those war days.

Dad retired as a master sergeant, and he began a second career at the Defense Construction Supply Center.

Dad passed away in 1981. We miss him still.