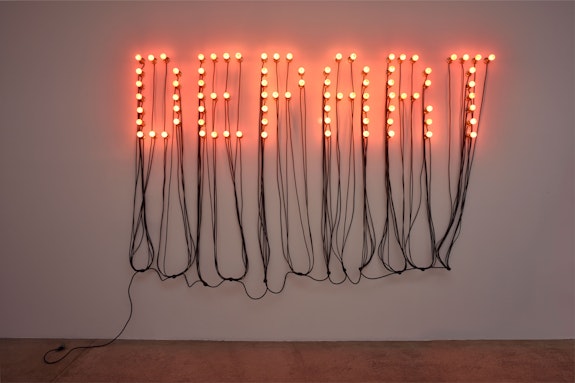

Christian Boltanski’s Life in the Making, his most recent retrospective on view at the Centre George Pompidou could be seen as a survey into five decades of the artist’s practice. Or as the artist hopes, it could also be seen as a fresh new take on his entire career. The show starts with the word “Depart” (departure) and finishes with “Arrivé” (arrival), to paraphrase him: it’s not like a train ride but more like an initiation journey.

Paris, France

The Pompidou CenterNovember 13, 2019 – March 16, 2020

Boltanski has long been one of France’s most renowned contemporary artists and since the late ’60s, a pioneer who paved the way for this country’s understanding of politics in conceptual art.

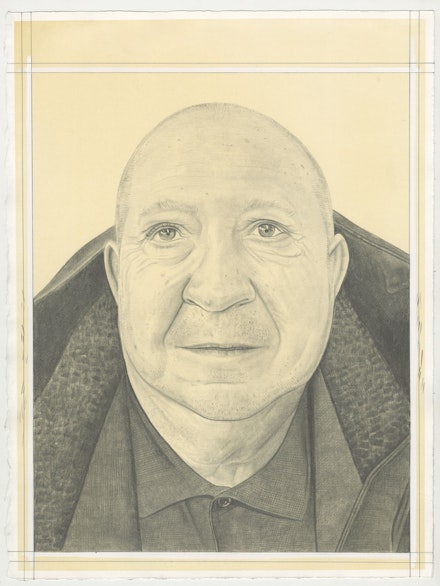

As the elevator doors of the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York open, I am surprised to see an ambient effervescence as the staff prepares for the gallery’s holiday party at Mr Chow. A charming presence, Boltanski introduces himself in French and we head to the library and start our conversation over a couple espressos.

Installations addressing the memory of the Holocaust and other tragedies have participated in building the reputation of a serious and grave personality but at 75, he is lighter than ever and for the Rail, he opens up about age, what it means to be living in what he calls his “overtime,” and how he sold his future death to a mysterious art collector.

Alexis Dahan (Rail): Have you ever lived in New York City?

Christian Boltanski: Yes, but it was only for one month. I think it was in the early ’80s when my girlfriend (Annette Messager) was at the PS 1 Studio Program. At the time, I was with Sonnabend Gallery and they had a very dirty place in SoHo where they would put their artists. So we had this very big studio on Crosby Street, but it was so dirty! There were no street lights, no restaurants, there was literally nothing!

Rail: And Sonnabend was in the same building as Leo Castelli (her former husband).

Boltanski: Yes, her gallery was on the third floor and his was on the second floor of 420 West Broadway. And I think I also had my second solo show there in 1989. I think the first show at her gallery was Gilbert and George. And I think the second show was me in 1974. There were very few galleries. I remember this building was very bare. Paula Cooper was the first one to move to SoHo.

Rail: On Prince Street in 1968. How old were you?

Boltanski: I was something like 30. You know I met Ileana [Sonnabend] in the mid ’60s when I was very young. I've always been very lucky in my life. Everything was simple. The first big event was Documenta 5 led by Harald Szeemann in ’72. This was the beginning. Then my work got attention in Germany and it spread everywhere. Harald was like a father to me. I loved him.

Rail: You also have a deep connection with Bernard Blistène.

Boltanski: Yes, he is my curator for my show at the Centre Pompidou and he was also the curator for the first show I had at the Centre Pompidou, which was in ’84. He was young and I was young and now he is rather old and I'm very old!

Rail: As long as one acts young one will never age… So let's talk about the exhibition a little bit because we are recording this in December and this will be published in February so there is still one month to go. Is it a retrospective?

Boltanski: It's a retrospective in the sense that it shows the first movie I made in ’68. And you also have a painting from ’67. But in fact, what I wished to do was to create one work altogether. This show is one work. Even if some parts are old and some are new it must be looked as one work. It's a way or a road. But not a road that begins in ’67 and finishes today. I really wanted to create an exhibition that is only one piece. Sort of like if you come back home and there's nothing to eat so you open the fridge and you find a carrot, some eggs, and other things and you put it all together to create something new.

Rail: So you change the integrity of each artwork?

Boltanski: Yes, absolutely. Sometimes I use artworks like materials or like a medium. This exhibition begins with the words “Départ” and finishes with “Arrivée.” These are new works. And in between, you experience the show like an initiatic journey.

Rail: It’s pretty rare for you to use words as artworks.

Boltanski: That’s true, I don't use words. I don’t like them so much. These two works really just say you begin and you finish. It’s my life so it is a kind of retrospective, there is a departure and an arrival. Just like in life, you get born and you die. Alain Resnais, the filmmaker, wanted to make a movie called “Arrivée, départ.” But he didn't have the time to do it. It's also the reason why I used these two words.

Rail: How is it initiatic?

Boltanski: Well, the beginning of the show is more sad than the end.

Rail: Did you ever get to meet or know Resnais?

Boltanski: No, but I deeply love his trajectory from tragic to comic. His work is definitely an inspiration for me.

Rail: And what about the title of the exhibition?

Boltanski: It’s very difficult to translate it because it’s a wordplay with an idiom.

Rail: In French, “Faire son temps” means you have expired, right?

Boltanski: Yeah, it means you are done!

Rail: But in English they named it “Life in the making” which means it is still in the process of being made.

Boltanski: Yes, the reason I chose this title is because it’s both. “Faire son temps” literally means making your time. You make your time. I make my time. But it also means: this is over, this artist already made his time, he is finished.

Rail: It’s a pity the translation does not have this.

Boltanski: I love titles with antithetic meaning. For example, when I made the piece at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2010 before it travelled here to the Park Avenue Armory. It was called Personne, which means either nobody or a lot of people.

Rail: But joking about yourself as if you were finished is a little tragic.

Boltanski: It’s ambiguous. When you are asked to make a retrospective, it basically means you’re dead!

Rail: [Laughs]

Boltanski: Much of what I do now is retrospectives anyway! These last few years I've had a very large retrospective in Shanghai, another one in Tokyo, in Jerusalem… Everywhere I go people ask me to do a retrospective and it’s normal, you know, because of my age so for this one I added a little joke.

Rail: Maybe you should have started your career with a retrospective!

Boltanski: [Laughs] I think, when you're an artist like me, you always speak about the same thing. When you travel somewhere it’s about the food you eat, the landscape you see or the friends you meet. It’s always the same trip, but each time you look at it in a totally different way. And I believe for an artist, it’s always the same work, but we don’t look at it the same way, whether we are young, middle-aged, or old. I think each artist only has one trauma at the beginning of their artistic journey.

Rail: The curator, Bernard Blistène, says about the exhibition that it tells the story of how you started as an archeologist of your own story, and then how you became a creator of myths.

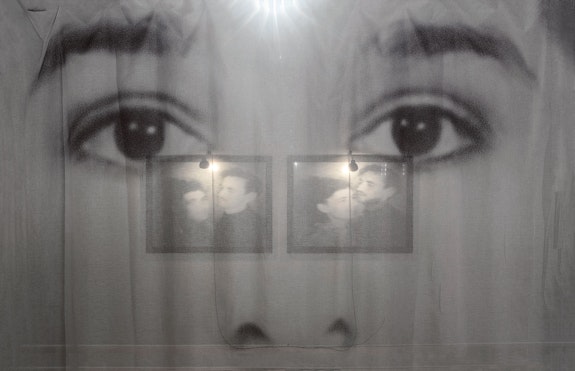

Boltanski: There were three moments in my story. When I became an adult there was the Photo album of the Family D, which was more conceptual. And another moment when I lost my parents with works that were more visual like Lessons of Darkness, the exhibition I had at the New Museum in 1989. And in the last 10 years, it’s been a new time for my work. Today, half of my work is destroyed after each show, but it can be done again. A little bit like a musical partition.

Rail: Do you mean like classical conceptual art where the work can just be the instructions?

Boltanski: Yes, but my work is tangible. There is only one artwork titled Personne and although it was shown at the Grand Palais in Paris, and in New York at the Park Avenue Armory, and in the Hangar Biccoca in Milano, in Japan and in Shanghai—there was never any shipping.

Rail: How does that differ from let's say a Sol Lewitt instruction?

Boltanski: It's a little bit the same but Sol Lewitt's instructions were always extremely precise. For me it is not precise. In Milano the piece was a certain way which was not how it was in Paris or in New York. I love that you can change it. Sol Lewitt is like a classical music partition and for me it's more like jazz. You can play with it, you can play with the space. In Japan it was outside and it was very, very hot. And in Paris, it was inside and very cold. It's totally different if you work outside with the heat or inside with the cold.

Rail: Does it matter how your work is received?

Boltanski: I was surprised the Centre Pompidou show was so well received by the French public because I didn't make so many shows in Paris. The last one was 14 years ago. I thought my art was not so good for the French public.

Rail: Why is that?

Boltanski: Because they’re French! They over-criticize. Germans love to be philosophical. Japanese people love to believe everything. French people love to doubt.

Rail: That’s the Descartes tradition.

Boltanski: Exactly. Are you really French? [Laughs]

Rail: I am expatriated and happy. And I don't think the French deserve France.

Boltanski: Me too! Though I was born in Paris, I feel more like a central European artist. As an artist I have no country. It's like Georges Perec wrote, “We are all born on Ellis Island.”

Rail: Georges Perec is perfect for you.

Boltanski: He is one of my favorite writers. He uses rules and at the same time he is very sentimental. I am a sentimental minimalist. Felix Gonzales–Torres was a close friend and for me, he was also a “sentimental minimalist.” He was using a minimal form but his work is full of feelings and emotions.

Rail: What other books by Perec do you like?

Boltanski: All of them but specifically I Remember (1978) and The Disappearance (1969) which he wrote without using the letter “e.” And for a lot of other reasons he is very close to me.

Rail: Do you know Perec personally?

Boltanski: I did not meet him and it’s a big disappointment. Once I was at a dinner in Andy Warhol’s Paris apartment without Andy Warhol and I saw Perec was on the other end of the table and all I wanted to do was go up to him and tell him “I love your work,” but I did not and he passed away two months later…

Rail: What about the other members of OULIPO (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle)?

Boltanski: I am a close friend with Jacques Roubaud. He made one book with sentimentality. But he's more of a mathematician while Perec was always about the coexistence of rules and feelings.

Rail: Are you still working with this framework?

Boltanski: No. Now I work with something a little different. I want to create legends and mythology. For example, there is an island in Japan called Teshima where I archive heartbeats. I have something like 80,000 heartbeats now. A lot of people visit the island not because I'm an artist or because they know my name. They go there to hear the heartbeats of their grandmother. It's not an art piece anymore, it’s a place of pilgrimage. Now I try to create legends like that. Do you know there is a man in Tasmania who bought my life?

Rail: Yes, I do know about your “pact with the devil” with the collector David Walsh. Is there some physical manifestation of these newer works in the retrospective?

Boltanski: There is my own heartbeat which is an old artwork but no heartbeats from the Teshima piece. It is important that you must travel to hear the heartbeats archive.

Rail: That is also part of this initiatic journey. However, I notice you can get a little USB key at the Centre Pompidou with a fragment of recording from The Life of C.B. (2010–ongoing)

Boltanski: Yes that is the Tasmanian work. It’s an inside joke because with these large museum exhibitions there is always merchandise at the end and it's always awful like a tote bag or something. I thought it would be much better to create a way to sell my life. And David Walsh accepted to sell a little part of my life because he has hours and hours of it.

Rail: How and when did your relationship with Walsh begin?

Boltanski: We were introduced by Jean-Hubert Martin, a renowned art historian who was a frequent visitor to Australia while performing research on aborigines. Martin was asked by Walsh to work on his collection and he suggested that we meet because my work has explored the theme of death and that also was a theme of Walsh’s collection.

Rail: How old is he?

Boltanski: I think in his fifties, he is young.

Rail: Imagine if he dies before you!

Boltanski: It was a big discussion that led to a complicated contract with a lot of lawyers. I wanted that if he died before me, his heirs would keep paying me every month. But he didn't want that. So the project will stop when the first one dies. If he dies before me then the project stops. He has millions of hours of recording already!

Rail: So, what is he recording right this second?

Boltanski: My empty studio.

Rail: Do you have to be in the studio a certain amount of time every year?

Boltanski: No. I'm free of that. At the beginning I tried to say hello and sometimes I would arrive naked! Now I totally forgot about the cameras. What is funny is that when you look at someone's life you can't have your own. For this reason he hired someone and this poor guy's job is to stay in front of the screens and look at me.

Rail: And it's not really you, only an image of you.

Boltanski: Yes! He really has nothing at the end. I don't do much and I don't work in my studio. I work on the computer, but I don't produce any objects.

Rail: When you began The Life of C.B. in 2009, were you aware of Jonas Mekas’s diary film in the ’60s or Dieter Roth’s Solo Scenes (1997–98), which comprises of 131 video monitors stacked in a grid showing his daily routine of the last year of his life?

Boltanski: I knew of the Mekas and Roth work but what I’m doing is very different. Life of C.B. is being recorded all the time, whether I’m there or not. So it’s constant until my death.

Nothing really happens. It’s just compiling thousands of DVDs in a library that no one will see. The recording is not the artwork as opposed to the works you mentioned that have been shown around the world.

Rail: So let's just focus on these three works: The Heart Archive (2008) in Teshima, The life of C.B. in Tasmania and Vanitas (2009) in Salzburg (where a speaking clock enunciates each second that passes). In a certain way, they all transcend time. Unlike your early works, they are not so much about the past and seem very much anchored in the present.

Boltanski: Yes you don't have to go to Tasmania to see the artwork because there's nothing to see. What is important is to know that the piece exists. That's what I mean when I say that I create a legend. It’s not about the object it’s about being aware of its existence.

Rail: If that knowledge is what matters in order to become what you call a legend, does the work even need to exist?

Boltanski: It is important that it exists in reality otherwise it would be too easy. And also I like the process of creating things. I like it when it’s difficult. In Salzburg with the bishop it was awful. He had to accept having some type of time machine under his cathedral. I also love how the information spreads. I call it a legend because like anything with oral transmissions it changes all the time.

Rail: Are there any other “legends” you are working on?

Boltanski: Yes and it can be seen in this Centre Pompidou show. It is called Misterios (2017) and I made it in Patagonia. For the Indians who live there, the whales are the animals who know the beginning of life, they know the truth. So I went there and asked questions about Misterios but nobody would answer me. So I decided to ask the questions to the whales. For this I made large trumpets and when the wind goes inside it makes noises that sound like the language of the whales.

Rail: Did the whales answer?

Boltanski: They never answered! Nobody sees the trumpets and they will be destroyed in six months. But I hope that this story is going to stay with the locals, I want them to say, “Once upon a time there was some crazy man who arrived and tried to speak with the whales.” And perhaps this story will become a legend for this place.

Rail: So you are trying to use transmission as a medium?

Boltanski: Yes. There are two ways of sacred transmission. One way, the Christian way, is to put little bones and protect them in a vitrine for example. The other way is like they do in the Shinto religion in Japan. They build a Temple and they destroy it every 20 years. And they build it again so all the temples in Japan are very fragile. There are always new and old at the same time. Japan influenced me a lot and I want to do similar things.

Rail: With this in mind, and since you were born in 1944, how would you say the development of information technologies has affected the way you work?

Boltanski: Well, because I work a lot with archives, it definitely had an effect. Now computers have the biggest archive you can ever imagine. I tried to work with Facebook. I wanted to look for all the dead people on Facebook. But it's difficult to do that. People think Facebook is something pleasant but in fact, it’s full of dead persons…

Rail: Or robots and people who don’t exist at all.

Boltanski: Yes. I'm a very traditional artist because my questions are always the same. And each time I try to speak with the language of our time so of course I use a computer for videos, photos, and sounds. Once I made an Internet specific artwork and it was a disaster… It was 10 little movies called “Storage Memory.” One minute per month and they were all for sale for one dollar. What is beautiful with computers is that you can touch everybody everywhere. At the beginning 500 people paid and at the end there were only two people so I stopped. Internet must be free, nobody wants to pay. The idea of Facebook is that it looks free. It's not really free though. To pay is not in the spirit of the Internet.

Rail: What other effects do you think the evolution of information technologies have had on the practice of art?

Boltanski: What is incredible is that you can be an artist in the middle of nowhere and know exactly what happened in New York last week. When I was young, it seemed that to be an artist it was important to live in New York but today you can make art and live anywhere. You can be in your village and have all the information on every new artist. I don't think computers have changed art. Not for me. I can use a computer to make my art but what is important is what I want to say. So whether I find information in some newspaper or on the computer, I don’t see any difference.

Rail: Now let’s talk a little bit about politics and how it affects your art. Some of your most well-known works are about the memory of the Holocaust.

Boltanski: I was born at the end of World War II. Most of my parent’s friends were survivors. My father was a survivor in a way since he was hidden by my mother under the floor of their apartment during the Nazi occupation of Paris. So I kept hearing all these stories and as a very little boy, it really changed my spirit. Today I believe we are still at war. Nothing changes. I don't believe we are in a time of peace. How many immigrants die in the Mediterranean Sea? This is war. There are places a little quieter than others. But in fact, if you think globally, we’re at war.

Rail: What can an artist do about it?

Boltanski: The function of the artist is to ask questions. I love to ask questions and I hate people who believe they have the answer. People with answers are very dangerous.

Rail: What do you think about people who think that art can change the world?

Boltanski: I think art cannot change the world. Art is a way to ask questions so somebody can ask another question.

Rail: Like Socratic Philosophy?

Boltanski: Yes, a question must lead to another question and another question. And perhaps that can help change the world. When people know there is no answer, the world will be a little better. To be human is to ask questions. My cat doesn’t ask questions.

Rail: What kind of cat?

Boltanski: A very normal cat. A stupid cat!

Rail: What do you think about the resurgence of identity politics in contemporary art?

Boltanski: 20 years ago the good artists were all gay or women because they had to fight and I think a good artist is always someone who has to fight. Now, I feel it’s coming back a little. For a long time, especially in the US, art was only something lovely or funny. But now there is a new generation who is trying to ask questions.

Rail: How about the evolution of the art market?

Boltanski: I became an artist in 1969. The relation with money was totally different as it is today. You know I have worked as a teacher all my life. When I was young, when an artist would sell his pieces, everybody would say, “Not good! Dirty!” which was stupid because we had nothing against them or money. But I think art is much more important than the money it costs. What bothers me is how art is becoming like a normal business. I think the worst thing you can say to a young artist is, “you are a professional.” That’s an awful thing to say.

Rail: Then what is the best thing you can say to a young artist?

Boltanski: You are crazy! [Laughing]. Which is a good thing. I was crazy but I'm not crazy anymore unfortunately. Now I'm a professional! Or professionally crazy!

Rail: Is that how you qualify this new period of creation for you?

Boltanski: My time now is “overtime,” just like in football. I like this idea. I’m more free.

Rail: What’s next in your overtime?

Boltanski: I have to go to Russia and start working for an exhibition at the Pushkin museum. I have a new project and you are the first one I'm speaking to about this project. I want to use Getty Images’ stock videos. I will pick very charming stuff like videos of baby deer in the morning, videos of sunsets, stuff with “feel good” images. And then I would insert subliminal images that nobody can see: Images of horror and wars. Dream and reality together as one.

Rail: You don't want to control the reaction of the viewer.

Boltanski: I believe that for my work, everybody can understand what they want to understand. If somebody says, “your work is so funny,” I'd be very happy. And for this reason, when you give an interview, you already say too much. The beauty of art is that everybody can see something different. If you go watch a movie at the cinema, everybody sees a different movie because of what happened to them the day before. You never look at a work of art the same way others do. My two favorite filmmakers are Federico Fellini and Stanley Kubrick. They are not very similar. I don't believe there’s only one way to make art.

Rail: What would you be if you were not an artist?

Boltanski: I'm an artist because I was born in France in the 20th century. But if I was born in Amazonia, I would have been a shaman. I don't speak with words, I speak with feelings, and that's why I love being an artist.