ArtSeen

William Blake

On View

Tate BritainWilliam Blake

September 11, 2019 – February 2, 2020

London

Since his death in relative obscurity in 1827, William Blake has experienced a continuous revival that has turned him into a sort of artists’ patron saint, or as DJ and producer Martha Pazienti Caidan calls him, perhaps half-cheekily, “a pioneer of slasher culture.” Certainly there are a few figures who incarnated the Romantic ideal of the artist willing to sacrifice it all to his vision as well as Blake. The son of a London hosier and haberdasher, trained to become a professional engraver, in his poetry and art, Blake posited himself as a lone visionary, a sort of prophet maverick engaged in upholding human freedom and imagination against all forms of tyranny and constraints, chief among them, “the mind forg’d manacles” of Enlightenment reason.

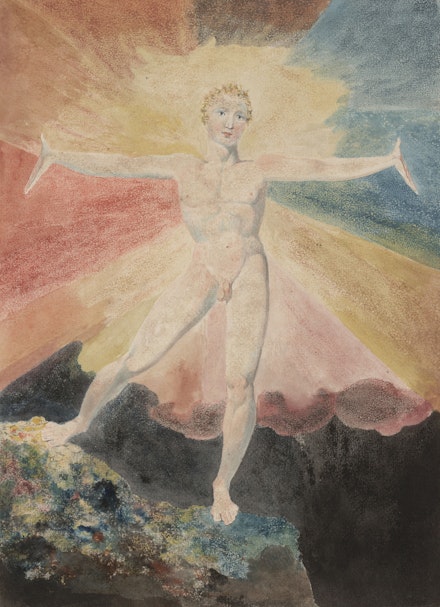

William Blake, on view at Tate Britain until February 2020, sets out to complicate this image of the artist perfectly exemplified in the famous illustration Albion Rose (1795) which welcomes the visitor at the entrance of the show. The intent is less to debunk or demystify than to contextualize and illustrate that despite his almost proverbial sui generis reputation, Blake was, after all, a man of his times. It is a fine balance to strike—by providing too much explanation, by complementing its piece with the names of its patrons and the history of its vicissitudes, the risk is that the magic of the work gets lost. And yet, Blake’s mythical halo emerges reinforced as a result of the effort at historicization that curators Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon have put on in this massive survey.

The first two rooms give an account of Blake’s beginnings as a professional printmaker and student at the Royal Academy of Arts, as well as of the time he spent perfecting relief-etching—“a method of Printing which combines the Painter and the Poet,” he called it—which later enabled Blake to produce his famous “illuminated books.” The two following rooms explore Blake’s thwarted attempts to establish himself as an artist, his frequent quarrels with friends and sponsors, and the bitterness resulting from the flop of his only solo show in 1809. The last section, meanwhile, recounts his encounter with “The Ancients,” a coterie of younger creators which helped to lay the first stone for his posthumous recognition as a “quintessential Romantic visionary.”

Outstanding art abounds, and the show is a unique opportunity to see it up close. Because they were meant to be featured in books as illustrations, most of Blake’s prints are quite minute and the visitor is granted the chance to experience them in their original form, in all their exquisite richness and subtlety. Time and time again in William Blake, I found myself losing track of the subject matter and focusing instead on its precious details or the overall feeling of the illustration. (If you get the chance, take a moment to dwell on the place where Newton sits in single-minded concentration in Blake’s homonymous watercolor: the anemone-like fronds which cover the rock are one of a kind.)

In Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1795), Blake writes, “The Reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” The same fascination holds true for Blake himself and in general, the art pieces that really stand out among the hundreds of prints, watercolors, and drawings are decidedly infernal. Of course, there is the hideous, humanoid beast of The Ghost of a Flea (1819–1820) with “his eager tongue whisking out of his mouth, a cup in his hand to hold blood, and covered with a scaly skin of gold and green”; other highlights are provided by The Number of the Beast is 666 (1805) and The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (1795), which, in its imagery, shows a striking resemblance to Francisco Goya’s Caprichos (1797–1798).

Of a different nature but just as compelling are Blake’s watercolors of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1824–1827) and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1824–1827). Narrating two journeys from dejection to salvation, these series were produced when the artist was already declining in health but not in imagination: “In that I am stronger & stronger as this Foolish Body decays,” he wrote in a letter dated 1826. Though they are unfinished pieces, these drawings often look more imaginative and playful than any illustration Blake ever produced (though some of the frontispieces he made in the 1790s are definitely on par). They are so rich in color that sometimes they can only be described as harlequinesque.

This late burst of inspiration might be because, by this point, Blake was backed financially by his younger admirers. Indeed, for much of his life, he struggled with a commercially driven art market in which the artist, if he wanted to survive, had to cater to the taste of private buyers. Much of what we praise as timelessly modern in Blake—be it his poetry or his art—was produced out of necessity, to pay bills and please wealthy patrons while Blake was waiting for his shot at becoming a painter of large-scale historical frescoes in the manner of Raphael and Michelangelo, something which never came. By proceeding chronologically and attending to the details of the artist’s biography as well as providing further contextual information, William Blake fleshes out Blake’s genius, grounding it in the tensions and ironies that made it possible.