ArtSeen

Dan Graham: Beyond

Whitney Museum of American Art, June 25, 2009 – October 11, 2009

Last summer, thousands of hipsters turned out to hear Sonic Youth close down McCarren Park Pool, playing the Williamsburg venue's final show. This summer, guitarist Thurston Moore is lending his indie rock cult-status to longtime collaborator Dan Graham, appearing in interviews and promotions for the 67-year-old artist's career retrospective. Opening June 25th at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the exhibition—showcasing Graham's pioneering work with Sonic Youth, experiments in performance and involvement in the early punk-rock music scene—is already being hyped to the twenty-something set as the hottest ticket of the season.

Personally, I’m thrilled with any hype that might lure a young crowd to Dan Graham: Beyond. Whatever they expect to see—flags, drum-sets, tinsel and skulls—the popular signs of art “influenced” by punk—will be superseded by Graham's nuanced and deeply intellectual output, none of which features the tropes of rebellion trendy in art today. Graham is a purveyor of high and low culture—virtually self-taught, with only a high-school education, he poured through the writings of Wilhelm Reich, Margaret Mead, Jean-Paul Sartre and the modern vanguards of philosophy. In mid-1960s New York, he befriended artists Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin and other titans of Minimalism, who further informed the aesthetic and ideological base of his artistic inquiry.

Dan Graham: Beyond surveys the artist’s exceptional, 40-year dedication to enlightenment and erudition—and to examining social codes, group behavior and established modes of perception. His extensive experiments in text, video, performance and installation make for a fascinating but challenging show, even for the seasoned museum-goer; the work is stark, theoretical and purposefully slow. Graham’s practice does not aim for ennui, but it does pursue a suspended relationship to time, requiring a patient mind-set. An early text-piece on view sets the tone—a simple paragraph on paper describes the physical sensation just post-orgasm—a lucid state of relaxation.

Graham began his career as a writer and critic. His preoccupation with language gave way to his early, text-based artworks. He devised instructional paragraphs and visual schemas, such as his 1966 work “Side Effects/Common Drugs”—a grid plotting prescription drugs like tranquilizers against side effects like blurred vision. Attracted to both the glossy immediacy of a magazine format and a subversive means of distributing art outside the gallery context, Graham designed the page with the idea of running it as an ad in Ladies Home Journal. Although Graham did publish other schemas, “Side Effects/Common Drugs” was never published. Still, it combined a conceptual art approach with the defiant spirit of rock ‘n’ roll. A nod to the Rolling Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper,” the message was that everyone in the 1960s—even the suburban housewife—was taking drugs.

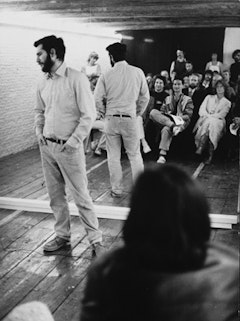

The appeal of a drug-state, or an altered state of consciousnesses, is a theme that runs through many of Graham’s time-based performances. In his 1969 performance, “Lax/Relax,” Graham sat before an audience with a tape recorder and a microphone. A pre-recorded female voice slowly repeated the word “lax,” to which Graham answered “relax,” creating an auditory experience that referenced both the echo-like time delay in a marijuana high, and the steady iteration used in hypnosis. Graham was attuned to both—the social space, leisure (“lax”) time and, it seems, the immediate pleasure of pot-smoking, the popularity of West Coast, new-age healing and group therapy—as vehicles of self-awareness. Graham’s focus on temporality and self-reflection soon introduced standard elements into his performances—wall-sized mirrors and video cameras, as mechanisms of surveillance and self-consciousness.

Graham’s architectural interventions with mirrors, and his experiments in perception led to the “Pavilions”—steel-frame and glass sculptures that are his best-known works. Close in scale to urban bus shelters, the pavilions’ glass surfaces are tempered and operate as two-way mirrors. Viewers are encouraged to walk inside through multiple planes of transparency and observe reflections of themselves, others, and their environment. The pavilions are site-specific—“Octagon for Münster” (1987) was built for the wooded path of a botanical garden, an eight-sided, mirrored exterior that almost disappears while fully reflecting the sylvan setting.

The pavilions on view in Beyond reflect the Museum's white walls, effectively emphasizing their formal construction. Graham designed them to be public art, to reflect the activity of urban landscapes and public parks. Context is an issue throughout the exhibition, and given the number of works Graham originally conceived to be site-dependent, the limitations inherent in the museum retrospective are inevitable. A valuable context-providing addition to the show is the exhibition catalog, which reproduces some of Graham's exemplary, previously published writing. His 1989 essay “Garden as Theater as Museum” astutely traverses the social and critical histories referenced by his pavilions—the history of glass window displays, the proliferation of shopping malls, consumerism and the power-structure born of corporate surveillance. Also featured are many excellent interviews, one with Sonic Youth front-woman Kim Gordon discussing Graham’s passion for astrology, The Kinks and feminism. Graham reveals that one of the reasons he focused his video “Rock My Religion” on the punk icon Patti Smith was that he wanted the hero of his video to be a woman.

“Rock My Religion,” a video that captures the late-70s/early-80s New York music scene, is here to watch in its rare, 55-minute entirety, and visitors should not miss a minute of it. Completed in 1986, the quasi-documentary chronicles a subjective music history, interpreting the fateful end of the hippie-era, and the dawn of garage-rock. Amateur concert footage offers a glimpse into the youth rebellion and hard-core sound—heightened by a Sonic Youth soundtrack—that characterized the punk scene. Performance and audience, drugs and dissent, the self and the collective unconscious—themes that Graham explored throughout his career—are presented here with an exhilarating energy. “Rock My Religion” is ultimately about music and art as a contemporary belief-system. Believers young and old should come out to witness the paragon of an extremely relevant artist and the sum of his convictions.