Dance

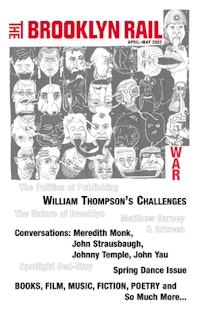

Sound Itself Is No Sound: A journey into process and performance with Meredith Monk

I never imagined waking up in total silence at Zen Mountain Monastery in the Catskill Mountains and rolling out from the top bunk of a freezing cold bed in absolute darkness at 4 a.m., all so I could understand the secrets of Meredith Monk’s work.

I never thought of using my soft city hands to rake a wide expanse of freshly mowed lawn in the blazing sun until huge blisters appear on my tender palms, all to penetrate the source of Meredith’s celestial songs.

But I did.

I would have endured even more to understand Monk’s unique pieces. She uses the original human instrument, the voice, or a “language of the heart that expresses the energy for which we don’t have words.” Meredith’s extraordinary presentations are referred to as “extended vocal technique and interdisciplinary performances.” A recipient of the MacArthur “genius” Fellowship, two Guggenheim Fellowships, three OBIE Awards, and a Bessie for sustained achievement, she has created over 200 works. In 1968 Meredith founded her company, the House, and in October 1999 performed a vocal offering for His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, as a part of the World Festival for Sacred Music in Los Angeles.

But How Does What We Think Create What We Do?

Meredith’s studio in TriBeCa is the creative factory where her basic technique is built. Pablo Vela, a colleague for many years, is teaching a movement workshop on a steamy hot day in July. The windows are flung wide open in a long airy room equipped with a well-used piano and a bank of rehearsal mirrors.

Eerily, everyone is absolutely still when I arrive, twisted in arcane, bizarre postures, like figures in a wax museum. Some stretch plaintive hands as if pleading for their lives, others bend over halfway, and still others lie splayed in heaps atop each other on the floor. One student clasps a fist over another’s mouth as if attempting to either silence or suffocate her. Another walks into the middle of the rumpus and completely freezes mid-step with her leg in the air. A participant rises up from the twisted heap of bodies and calmly walks away. I feel like I am watching a film in first slow, then fast motion, randomly edited in a disjointed rhythm.

“The movement should be unpredictable, but you should be completely present, like you are walking down a New York City street,” Pablo says after it’s over. The trick is to “find a balance of structure and spontaneity, freedom and form.” One dancer comments, “I had no sense of time. It just felt like it was this huge journey, like it was all just energy, and the energy changed throughout time. I was thinking about patterns.”

Another reason for the exercise, Pablo explains, is to “build the ‘feel’ of an ensemble,” both in rehearsal and in performance. The dancers’ job is to focus on the invisible place between each other’s motion, and to touch the tendrils of “energy” that mold raw sense perception into muscular shapes and motion.

At The Zendo

Meredith herself gives a voice and performance workshop at Zen Mountain Monastery, a serene, densely wooded enclave in Mt. Tremper, close to Woodstock, New York. The head Roshi, John Daido Loori, is a huge supporter of the arts and also an avid author, photographer, and poet. In fact, we are told that “art practice” is considered one of the Eight Gates of Zen, the seven being Zazen sitting, study, lineage, body practice, Buddhist studies, work, and right action.

The monastery, a Tudor-style building, is the former home of a Christian brotherhood. The first night, we sit inside the Zendo shrine room alongside the monks and nuns wearing their gray, black, and white robes. I see calligraphy of a joyous, naked dancing monk in the throes of enlightenment on the wall behind us. Everyone chants in clipped, crisp Japanese and I wonder if Meredith is contemplating the raw harmonics of these new sounds.

We wake up at 4 a.m. the following morning while the moon shines coolly from behind the mountaintops. We line up in a straight row to walk single file into the somber meditation hall. Sitting on stuffed black zabutons and zafus, we become aware of any little movement because, as we saw the previous night, we can’t move. It’s not torture, but a voluntary system of rigidity, rote routine, and compression, so there is only one way to go— inward. The whole world becomes included in such a miniaturized view.

Suddenly I hear a loud "thwack." One of the students asked to be struck on the side of his neck with a flat wooden paddle, a very traditional practice designed to keep the meditator awake. After 45 minutes we do walking meditation, called kinhin. I place one foot in front of the other and follow the little white arrows taped onto the floor to guide me.

Work period follows a brief breakfast. My job is to rake an enormous expanse of cut lawn. Within 15 minutes, huge, watery blisters rise up on my palms. By the time I finish wrapping Band-Aids around them, it’s time for Meredith’s workshop.

The Sound of No Sound

We start with exercises “meant to produce movements of body and sensory awareness.” Participants team up and sing with their backs pressed against each another, which makes each person’s chest act as a harmonic cavity. The chorus of “ahhhhs” is a waterfall of sound. Meredith instructs us to close our eyes and locate our partner’s voices from amongst the whole group of “ahhhhs.” People move about like blinded animals, trying to recognize the one specific “ahhh” from all others. This seemingly nonsensical technique winds up in a scene from her three-hour opera, Atlas, about the life of the French exploress, Alexandra David Neel.

A tremendous sense of humanity pervades Meredith’s work, and she views every voice as a gift. “I got the courage after 9/11," she says, “to do this as an offering, using just the onomatopoeic word ‘shingway.’” This word evolved from locating melodies that transport her to the place of the sacred using just a few tones. “Shingway.” It’s a word without meaning. But if you say it while reading this article, hold it for an extra second at the “ing” or the “wAy”; say it a few more times. Drop the sound. Bring it up again. “ShinGway.” “ShingWay.”

Sunday with Daido Loori

It is a Sunday morning tradition at Zen Mountain Monastery to present discourses. Even though Zen relies at its core on unmediated experience, Roshi John Daido Loori stresses deep reflection upon those experiences. Participants and monastic residents file into the cold shrine room to hear him discussing Master Benrin’s "Sound Itself Is No Sound," part of Master Dogen’s 300th koan, “Shobogenzo.”

“I have been putting off certain koans and did not know why,” he tells us. “This one on sound by Benrin was a particularly knotty one, for it discusses aspects of the dharma that cannot be discussed, making real that which is invisible. Artistic communication initiates something already in the individual, and brings it out. There is not some special spiritual force that exists separate from the phrases we utter or the forms we perceive. If you understand this, you have entered the place Benrin speaks of.” His eloquent, booming voice enunciates each syllable as if he were exchanging koans during a Dokusan interview. Continuing, he says, “Last night during Meredith Monk’s performance, as I closed my eyes and leaned my head back and let those sounds in, I was transported to someplace else that was familiar, that was primordial. I recognized it, but I had never gotten in touch with it before.”

While Roshi speaks, Meredith sits at the front of the Zendo and bows her head. This extraordinary admission from a fully enlightened Zen master attests to the grandeur of her work. Zen is always a transmission outside of scriptures, with a direct pointing to the human mind; Roshi confirms that art can do the same thing. He does it at first by arguing that words and paintings do not actually describe reality, they just point to it. But in a complete reversal typical of Zen logic, he tells us that Master Dogen said words and painting do describe reality, and that symbol and the symbolized are the same thing. Otherwise, how can anything be communicated? Spirit and matter are the same reality. When too much is added to it, only then does it become intellectualization.

“There is not a force that exists outside of the phrases we utter, the ordinary language we utter, or the ordinary forms that we perceive… And art can be a process of making visible that invisible aspect,” Roshi says.

Making the Invisible Visible: “Mercy”

Meredith and Ann Hamilton, a visual artist, created the hour and half piece “Mercy,” juxtaposing fragile, original, and evocative moments that sift between the layers of dreamscape and real life.

Lanny Harrison, sitting in the audience, rolls a string that is onstage over a piece of vellum, which causes it to unfold like a tablecloth set for a dinner party. Meredith enters and sits down across the table from Ann. With a tiny light attached to her wrist, Ann shines a beam on Meredith, who intones the Tibetan mantra, “Om Ah Hum.” An image appears overhead on a large screen consisting of Meredith’s mouth opening and closing. Ann draws a line on the vellum as the miniature camera focuses on the spot where the pencil meets the paper, concept meeting execution.

Sepulchral voices sing Gregorian chants as the performers gesture at each other in a subdued motion. A man’s out-of-focus face is projected overhead. Angry. Who is he looking at? Another man’s mouth is contorted. Who is he calling to, pointing at?

Lanny tapes a piece of opaque paper across her face to resemble a torture victim, or disappeared person, her hands tied behind her back. Meredith walks onstage wearing a bathrobe, pushing a chair on wheels. A doctor checks her ailments by shining a light on her. She retaliates by using a tiny camera to blow up an image of his face on the overhead screen, then sings:

Help

Ail

Help

Hail

He mouths back at her:

Help

Hail

They synchronize together, using the words:

Woe

Woe

Woe

Hep a helpa help

Doctor and patient then both collapse.

The wings of the theater burst open in a blast of light, and groups of Eastern Europeans walk up to the stage carrying boom boxes. Their wraithlike figures project overhead, resembling holocaust survivors or slaves. A woman wearing a Muslim headscarf, several small children, and a group of Asian internment-camp detainees join them. A man sits on his haunches like a prisoner in the Vietnamese jungle—a severe-looking woman walks around him, shining a light all over his body. Meredith crawls on her stomach and pushes a piece of paper and pen over to him. He speaks an unintelligible language but writes in English, the simple act of communicating making him human. She stands up and rips his paper in two. But he retains the pen.

Two clear nylon strings slowly descend from the ceiling, weighted at the end with a fish-line sinker. Soapy water dribbles down the strings. Two women pull the strings apart to form an enormous, tensile bubble. They sing into it, and their rippling breath causes it to quiver, then burst apart. A gentle spray of soap mist bathes the singers. Pieces of paper flutter down like confetti and land with an audible pap or a plop. The audience gasps with the shock of recognition—it’s just like the World Trade Tower debris.

People assemble amongst the debris. The tiny camera ranges over printed words on the papers of a book: "ogre," "unacceptable," "perverse," and "belly of the dragon"; "bogeyman," "fear," and "inhuman."

The piece ends. I can’t leave. I remain, mesmerized.