Chapter IX

After leaving the town, Louise continued walking for a moment longer, then attracted by certain combinations of colour, she stopped on the very spot where, the previous evening, we had watched the firework display.

The dawn, shining from behind the magnificent trees of the Behuliphruen, produced curious, unexpecred lighting effects.

Talu himself chose a favourable spot for the fascinating test which had been promised, and Louise, opening the bag her brother carried, unpacked a folded object which, once it was opened into its normal position, formed a strictly vertical easel.

A new canvas, stretched tightly over its inner frame, was placed half-way up the easel and held firmly in place by a screw clamp, which Louise lowered to the required level. Next, the young woman, with gret care, took from a box, made to protect it from any contact, a palette, prepared in advance, which fitted exactly into a special metal holder fixed to the right side of the easel. The colours, placed well apart in little heaps, were arranged in a semi-circle with geometrical precision, on the upper part of the thin wooden board, which like the empty canvas, was set up facing the Behuliphruen.

In addition, the bag contained a hinged stand, similar to a camera tripod. Louise picked it up, then lengthened the three extending legs, which she set down on the ground not far from the easel, anxiously adjusting the height and stability of the apparatus.

At that moment, Norbert, obeying the instructions of his sister, took the case, to place it behind the easel, a heavy chest whose glass lid revealled several batteries arranged next to each other.

In the meantime, Louise was slowly unpacking with, with infinite caution, a utensil, doubless very fragile, which looked to us like some thick, solid plate, protected by a metal lid which corresponded exactly with its rectangular shape.

Distinctly recalling the skeleton of a weighing-machine, the top part of the three –legged support consisted of a sort of fork, with two widely diverging prongs, which ended up abruptly in two vertical arms, on which Louise was able to fix one of the long sides of the plate, cautiously assembling it by using two small, deep holes, correctly placed at the point where two grooves at the back, carved out to facilitate the sliding movement of the sides encompassing the lid, projected.

In order to appraise the disposition of the various articles the young woman, screwing up her eyes, stepped back towards the Behuliphruen, in order to judge their relative distances more accurately. From this position she could see on her right the stand, on her left the easel with the chest behind it, and, in the centre, the palette with the paints.

The lid of the rectangular plate, with a ring in the centre by which it could be grasped, was directly exposed to the light of the dawn; from its back, completely unconcealed, sprang a myriad of fine metal wires, giving it the appearance of a head of hair growing too evenly, which seemed to connect every imperceptible area of the surface with a kind of machine charged with a supply of electric energy. The wires were twisted together to form a thick coil, wrapped in insulating material, which ended in a long bar, and this, Louise, returning to her post, bent down to plug into a socket in the side of the box of batteries.

The bag also furnished a strong vertical tube, somewhat in the form of a photographic head-rest, standing firmly on a circular base and fitted at the top with a screw, which turned easily, and could fix an iron rod inside at a convenient height.

Placing the device in front of the easel, Louise pulled the movable rod up out of the tube and tightened the screw, carefully verifying the level reached by its highest point, which was exactly opposite the still untouched canvas.

On this single, steady point, as if it were a game of cup and ball, the young woman planted a large metal sphere, fitted horizontally with a short hinged arm on a pivot extending in the direction of the palette, in whose tip were inserted some ten paint brushes, radiating like the spokes of a wheel lying on its side.

Soon the operator had contrived to establish communication between the sphere and the electric box by means of a double wire.

Before beginning the experiment, Louise, uncorking a little oil can, poured a drop of oil on the hairs of each paint brush. Norbert moved away the bulky suitcase, almost empty now that he had extracted the metal sphere.

Throughout these preparations, the day had been slowly breaking, and dazzling rays of light flashed among the trees in the Behuliphruen, turning it into a many-coloured fairyland.

Louise could not stifle a cry of admiration as she turned to look at the splendid magic garden which seemed to have been illuminated by magic. Judging the moment incomparable and miraculously propitious for the realisation of her plans, the young woman went up to the stand with its threefold ramification and seized by the ring the lid which fitted over the metal plate.

All the onlookers crowded round the easel so as not to offer any impediment to the luminous rays.

Louise was clearly moved when the moment came to undergo the great test. Her musical respiration quickened, increasing the frequency and the power of the monotonous chords continually emitted by the tags of her shoulder-knot. With a quick movement she snatched off the lid, then retreating behind the tripod and the easel, joined us to watch the movements of the mechanism.

Deprived of its shutter, which the young woman still held between her fingers, the plate now stood exposed, revealing a smooth brown, shiny surface. All eyes were fixed eagerly on this mysterious substance, endowed by Louise with strange, photo-mechanical properties. Suddenly, opposite the easel, a slight shudder ran through the automatic arm, which consisted of an ordinary, bright, horizontal blade, bent in the middle; the adjustable angle of the elbow tended to open as wide as possible, owing to powerful spring, whose effect was counteracted by a flexible metal wire, which, emerging from the sphere, was fastened round the furthest tip of the arm and thus regulated the gap; at present the wire was being stretched to allow the angle to become progressively greater.

This first sign of activity caused a slight stir among the restless, uneasy, audience.

The arm slowly extended towards the palette, while the horizontal, rimless wheel, created on the end of it by the star of brushes, was gradually raised to the top of a vertical axle, wound upwards by a cogged ring which was directly connected to the sphere by a highly elastic driving belt.

The two actions combined brought the tip of one of the brushes on to a thick supply of blue paint, in a pile near the top of the palette. The hairs quickly became stained, then, after a short descent, spread the particles they had picked up over a clean section of the surface. A few specks of white, gathered in the same way, were deposited on the place which had been stained blue, and the two shades mixed perfectly by a prolonged stirring, gave a very subdued pale blue.

Slightly shortened by the tautening of the metal wire, the arm swivelled a little and stopped higher up, in front of the left corner of the canvas fixed on the easel. Immediately the brush, impregnated with the delicate shade, automatically drew a narrow, vertical strip of sky down the side of future picture.

A murmur of admiration greeted this first broad brush stroke and Louise, thereafter assured of her success, let out a long sigh of satisfaction, accompanied by a noisy fanfare from her aglets.

The wheel of brushes, coming back to face the palette, suddenly began to turn, driven by a second belt made of the same expandable material, which disappeared inside the the sphere. There was a sharp snap as a stop-catch fixed another brush with new, unblemished hairs firmly in the place of honour. Soon, several primary colours, mixed on another part of the palette, made up a golden yellow pigment full of fire, which was carried to the picture and contained the vertical band already begun.

Turning to look at the Behuliphruen again, it was possible to verify the absolute exactness of this sharp juxtaposition of the two shades which composed a line clearly marked in the sky.

The work proceeded with precision and speed. Now each time the palette was visited, several brushes in turn concocted their various mixtures of colour; returning to the picture, they followed each other in the same order, all laying on the canvas, sometimes in minute quantities, their particular new tint. This process made it possible to achieve the most subtle gradations of tone, and, it by bit, one corner of a landscape, vividly true to life, spread itself before our very eyes.

Without taking her eyes off the mechanism, Louise gave us some useful explanations.

The brown plate alone set the whole process in motion, by means of a system based on the principle of electro-magnetisation. In spite of the absence of any lens, the polished surface, owing to its extreme sensitivity, received enormously powerful light-impressions, which it transmitted by means of the countless wires inserted in the back to activate a whole mechanism contained within the sphere, whose circumference must have measured more than a yard.

As we were able to ascertain with our own eyes, the two vertical arms which terminated the fork at the top of the tripod were made of the same brown substance as that of which the metal plate itself was composed; because they were so perfectly adapted to each other, they formed together a homogeneous block and were now contributing in their special field, to the continued progress of photo-mechanical communications.

According to the disclosures of Louise, the sphere contained a second rectangular plate, fitted with another network of wires, conveying the polychromatic sensations of the first, and, through this a thin metal wheel moved from section to section, while the current it set up drove a complete series of crank arms, pistons and rollers by electricity.

The work advanced progressively from left to right, still in vertical strokes, sketched in rapid succession, from top to bottom. Each time the rimless wheel revolved in front of the palette or in front of the canvas, a sharp click could be heard as the catch fell shut to hold one brush after another steady throughout the duration of its task. This monotonous noise was like a very slow imitation of the whirlygigs at a fair.

The whole surface of the palette was now touched-in or broadly smeared; the most incongruous mixtures of colours were placed side by side, constantly being altered by the fresh addition of one of the primary colours. There was no confusion, in spite of the disconcerting bright medley, and each brush was assigned to a particular category of shades, so that it was confined to a certain, more or less limited speciality.

Soon the whole of the left side of the painting was finished.

Louise followed with delight the movements of the apparatus which had functioned so far without any mishap or error.

This success was never once threatened during the completion of of the landscape, the second half of which was painted with amazing assurance.

A few seconds before the end of the experiment, Louise had once again passed behind the easel and then behind the tripod in order to take her place near the sensitive plate. By this time there only remained in the top right-hand corner of the canvas a narrow white line which was quickly filled in.

After the last stroke of the brush, Louise promptly replaced the obturating cover on the brown plate, stopping the hinged arm by this simple action. Then, free from any anxiety concerning the mechanical process, the young woman was able to examine at leisure the picture which had been executed in such a curious fashion.

The tall trees of the Behuliphruen were faithfully reproduced with their magnificent branches, whose leaves, of a strange colour and shape, were covered with bright reflections. On the ground, large flowers, blue, yellow or scarlet, sparkled among the moss. In the distance, through the trunks and the branches, shone the sky; at the bottom, a first horizontal belt of blood-red faded into a strip of orange just above it, which in turn became lighter, giving birth to a bright golden-yellow; next came a pale blue, almost white, in the heart of which, on the right, shone one last, late star. The finished work, seen as a whole, gave an impression of uncommonly intense colouring and remained strictly true to the original as each person was able to confirm by a quick glance at the actual garden.

With the help of her brother, Louise, unwinding the clamp of the easel, replaced the painting with a block of the same size, consisting of a thick pile of sheets of white paper, placed one on top of the other and joined at the edges; then removing the last paint brush to have been used, she inserted a carefully sharpened pencil into the empty space.

In a few words we were informed of the aim of this ambitious young woman, who now wished to submit for our examination a simple drawing, whose lines would naturally be more precise and more detailed than those of the painting and which required her only to press a certain spring in the top of the sphere to make a slight adjustment to the internal mechanism.

In order to provide a complex and animated subject, fiteen or twenty of the spectators went, at the request of Louise, to arrnage themselves in a group a short distance away. Seeking to produce an effect of life and movement, they posed as passers-by in a busy street; several of them, suggesting by their position that they were walking with rapid strides, bent their heads with a look of deep concentration; others, more relaxed, gossiped together like couples taking a stroll, while two friends exchanged familiar greetings as they passed each other at a distance.

Instructing them, like a photographer, to maintain the utmost immobility, Louise standing near the plate, sharply removed the cover and then made her usual detour, to come and watch the action of the pencil from near at hand.

The mechanism, reset at the same time as it had been adjusted by the action of pressing the spring on the sphere, slowly swung the jointed arm to the left. The pencil began to run up and down the white paper, following the same vertical sections, previously marked out by the paint brushes.

This time, there were no journeys to the palette, no changes of instrument, or mixing of paint to delay the work, which made swift progress. The same landscape appeared in the background, of secondary importance this time, and was blotted out by the figures in the foreground. The gestures, taken from life – the mannerisms, very marked – the silhouettes, strangely amusing – and the faces, blatant likenesses – all had the desired expression, sometimes gloomy, sometimes gay. One person’s body, leaning slightly towards the ground, seemed to be bent by the impetus of walking briskly forward; another’s beaming face denoted pleasant surprise at an unexpected meeting.

The pencil glided lightly over the page, leaving it often and in a few minutes it was covered. Louise, returning to her post at the appropriate moment, replace the shutter over the plate, then beckoned to the models, who came running to admire the new picture, delighted to move around after their prolonged immobility.

In spite of the contrast of the setting, the drawing gave the exact impression of a street of busy traffic. Each one recognised himself without difficulty among the compact group, and the warmest congratulations were lavished on Louise, who was excited and happy.

Norbert set about dismantling all the accessories, to pack them back in the suitcase.

In the meantime, Sirdah conveyed to Louise the complete satisfaction of the Emperor, who had been amazed at the perfect manner in which the young woman had fulfilled all the conditions he had strictly imposed.

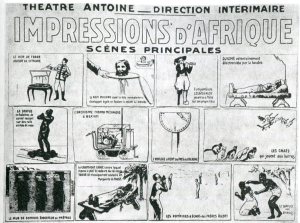

Raymond Roussel, 1877-1933 Impressions d’Afrique, 1910 Impressions of Africa: A Novel

Translated by Rayner Heppenstall. Published by Calder & Boyars Ltd, London, 1983

Louise Montalescot’s fantastic painting machine in Impressions d’Afrique introduced the concept of a machine that can paint, and consequently the generation of images through chance, which influenced Duchamp, Picabia, Dali and other Surrealist artists as well as avant-garde writers. Montalescot was ‘Particularly fanatical in her devotion to chemistry, she keenly pursued, during the long night watches, an important discovery long germinating in her mind. The problem was to generate by purely photographic means, a motor force sufficiently precise to guide a pencil or brush with certainty.’ Impressions d’Afrique was published as a novel in 1910. Roussel adapted it for the stage and presented it at the Théâtre Fatima in September 1911. Duchamp, Picabia and Apollinaire attended the play when it reopened in May 1912.