Uploaded 30 June 2000

Robert Aldrich was born in 1917 to a Rhode Island banking family, related on his mother’s side to the Rockefellers. His privileged youth led to a blue-ribbon university at which he devoted his energies to football, and to booking and promoting dance bands. During this period, he became interested in the movies. He directed thirty of them from 1953 to 1981. He died in 1983.

Studio apprenticeship, television break

In 1941, family influence got him a job as production assistant at RKO. He worked his way up to first assistant director and production manager, establishing a legendary reputation – before directing his first film – for bringing pictures in on or under schedule and budget. Joseph Losey recalls being an insecure young film director whose apprenticeship had been in live theatre. As he tells it, his producer, Sam Spiegel, told him:

“You’re right for this, but you’re not very experienced. I’ll give you the the best cameraman in Hollywood, the best technicians, the best first assistant. I don’t care what I pay, and you do it any way you want to.” This was extraordinary…As cameraman he gave me Arthur Miller…[who] had three Academy Awards; he gave me one of the best operators in the world, and he gave me Aldrich, God bless him…[1]

Although this is the first time Aldrich’s name had arisen in the interview, Losey identifies him only as “Aldrich” as if this were a commonly known synonym for “top assistant director”.

From 1945 to 1952, Aldrich free-lanced as a first assistant director, working frequently on United Artists productions, but also at Columbia, Paramount, MGM, Republic, Twentieth Century-Fox, Warner Brothers, Universal, and RKO. He also worked on Enterprise and Eagle-Lion productions during this period, which gave him experience in the new independent production sector. Aldrich worked for: Charles Chaplin; Jules Dassin; Richard Fleischer; Albert Lewin; Joseph Losey; Lewis Milestone; Abraham Polonsky; Jean Renoir; Robert Rossen; Frank Tashlin; William Wellman; and Fred Zinnemann. Not only is this a list of very distinguished filmmaking mentors, it also includes the leading edge of Hollywood’s political left at a particularly political time in the American film industry. (Aldrich’s vigorous leftist stance was never in doubt, though it was less idealistic and more defined by what it opposed and rejected. He served two terms as a very activist president of the Directors Guild of America, winning new rights for directors over their films; he claimed producers and studios never forgave him for this victory).

In 1952, after several failed attempts at setting up his own film directing projects, Aldrich shifted his attention to opportunities in the new and growing television industry. With network television only four years old (roughly), television production in Hollywood was surfing the first wave of syndicated film product as it replaced network live-to-air shows. During 1952-1953, Aldrich wrote and directed numerous episodes for The Doctor, The Affairs of China Smith, The Schlitz Playhouse, and Four Star Playhouse, serving as production manager and assistant director on some of these. Having established himself as a director in the tightly efficient time and budget constraints of television production, he got his first feature film assignment the next year: The Big Leaguer (USA 1953), an undistinguished MGM B-picture.

Robert Aldrich and I

The first live-action feature film I can remember is Aldrich’s Apache (USA 1954). I was ten. I knew nothing of directors or revisionist westerns, and the only parts of the film I can remember contain – barely – Burt Lancaster’s body in extreme motion, or his face set in steely defiance. For years I wanted to be Robert Aldrich’s Lancaster, until I discovered Errol Flynn, Fred Astaire, and finally, Daffy Duck. In any case, my first impression of Aldrich’s cinema was of his kinesis and intensity.

Aldrich’s work had gained an earlier foothold in our family culture, although (like Theodor Adorno – see Bill Krohn’s article elsewhere in this issue) none of us knew who Aldrich was. My mother and father prized the Willie Dante episodes of Four Star Playhouse (USA 1952-1956) Aldrich had directed in 1953. Played by Dick Powell as a continuation of the noir persona he began crafting in Murder My Sweet (USA 1944), gambler-saloonkeeper Willie Dante combined the worlds of the gentrified hardboiled and the boulevardier. In my memory (that great enhancer and deceiver), these inconsequential episodes were presented with an effortless control of pace, wit, and ambience which, in our household, was taken for an uncommonly cosmopolitan sort of television indeed. In hindsight, they were early demonstrations of Aldrich’s mastery of style – and his reliance on it.

In the late 1960s, I saw what I remember as a 70mm print of The Dirty Dozen (USA 1967) in a big Chicago first-run house, but what was most important was hearing it. For the first time, I could hear different levels and layers of the soundtrack or what we now call sound design. Of course, I knew about sound mixing and music/dialogue/effects as separate tracks, but this was my discovery experience of the manipulation of levels, volumes, registers, and apparent spatial relationships. None of this seems to survive in current videotapes, 16mm prints, or television screenings. And of course, being Aldrich, and worse, being Aldrich making a naughty boys film, the first thing that called attention to the sophisitication of Claude Hitchcock and Franklin Milton’s sound work was an ensemble dialogue scene in which, behind the principle dialogue, one could just hear, if one tried hard, John Cassavetes’ Franko character muttering obscenities.

In the early 1970s, I was teaching Vera Cruz V(USA 1954) because I liked it and thought we could learn from it things about Aldrich and the western. This was a moment in film culture in which structuralism and narratology were prominent, to say the least. As we talked about the film, I had another moment of epiphany: the surface of the film lifted and I could see, like a blueprint, the narrative structure in all its symmetries, reverses, balances, repetitions, and inversions. My gestalt moment was contained in watching, or perhaps talking about, Vera Cruz.

Not long after that, I went to see Aldrich’s Great Depression proletarian epic, Emperor of the North Pole (USA 1973) at a big, unclassy theatre on Hollywood boulvard with an audience of mainly young, mainly black and chicano, people. The theatre was packed, several hundred people. At the end of the film’s triumphant final sequence, the entire audience spontaneously stood and cheered: a standing ovation, something I had never seen in a movie theatre before, and only once since, when I went to a similar theatre to see Aldrich’s The Longest Yard (USA 1974).

Situation of the new director

The industry in which Aldrich began his career had enjoyed decades of relative institutional stability. Suddenly it was undergoing profound changes, all of which would effect and mould his career options as a filmmaker. These changes include: the phenomenon of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (USA 1941) and the ensuing re-definition of the role of directors in the industrial culture; the 1948 divestiture decree; the simultaneous rise of network television; the re-designing of United Artists, a model subsequently taken up by all the major studios; the growth of a viable independent production sector; the proliferation of personal and independent production companies; and globalisation of capital in the form of international co-productions [2] . While Aldrich has usually been written about in terms of style, theme, or genre, it may also be useful to approach his career in this industrial context. Aldrich, of course, was not alone in this situation. He was one of a generation of new directors during the period. A look at the career profiles, options, and choices of other representative members of that genereation will provide a context in which Aldrich’s situation and his responses to it can be better understood.

After Welles

Herodotus is often “quoted” as saying that in history, only some things happen when they should and the rest do not happen at all, but the conscientious historian will rectify these shortcomings. Felicitously, Aldrich went to work in the film industry at RKO in 1941, the very year and studio in which Orson Welles completed his first and most influential film, Citizen Kane. I have found no record of contact between Aldrich, the young production gofer, and Welles, RKO’s child prodigy one moment and bête noire the next. But the co-incidence establishes Aldrich’s credentials as a member of the generation of directors who came up through the Hollywood system and who made their feature debuts post-Kane, and very much aware of it.

Aldrich’s generation included these major post-war filmmakers: Budd Boetticher (b. 1916), Samuel Fuller (b. 1911), Joseph Losey (b. 1909), Ida Lupino (b. 1918), Anthony Mann (b. 1906), Nicholas Ray (b. 1911), and Don Siegel (b. 1912). All would make their feature directing debut between 1942 (Mann) and 1953 (Aldrich). As directors, they came of age after the older model of “director” as corporate stylist within the studio system had been flamboyantly superceded by Welles the auteur and complete filmmaker, outstripping and surmounting the studio, mythically bigger than the system. Certainly, young people had aspired to become film directors before Welles (obviously: Welles himself so aspired), but usually in studio-contained terms; novelist and screenwriter Horace McCoy uses this device in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?(1935) in much the same way Preston Sturges presents it in his own Citizen Kane, Sullivan’s Travels (USA 1941). The director figure (often producer-director figure) had been established with the ascendancy of D.W.Griffith. Subsequent cases include von Stroheim, DeMille, Lubitsch, and Hitchcock. All of these have to do with authority, power, an executive command of film craft, and general claims of “genius”: von Stroheim with excess (negative: profligate, becoming a prototype of the Orson Welles career myth); DeMille too with excess (positive: spectacular); Lubitsch with something moving toward style (a “touch”, denoting sophisticated European wit); and Hitchcock navigating between style and technique (the mastery of suspense). Welles, a consummate connoisseur and synthesist, repackaged the best of what had gone before him and sold it as something new, which it was, too; and he sold himself as a new type of director/filmmaker, which in his way he was, too – certainly to the aspirants of the next generation (Aldrich et al) for whom he reinvented the role and meaning of “director”. Each in their way embraced and exploited the Welles model of a cinema of personal style and vision growing from and supplanting the classical studio cinema; and also like Welles, they would not only direct but also write, produce, and/or act.

Vertical disintegration

The post-Kane class of directors also encountered a rapidly changing environment in the fall-out of the 1948 US supreme court Paramount et al divestiture decree which broke the vertical integration of the studio system. The major studios were forced to divest themselves of their theatre chains, upon which the stability of their long-term production planning rested, and to make changes in their distribution practices. Over the next decade, these major structural changes broke the old studio production system and opened opportunities for new production, distribution, and exhibition configurations. And, just as Welles and Kane redefined the film director, the divestiture decree reinvented the film studio – or more precisely, allowed United Artists to do so.

Outsourcing the studio

Eagle-Lion Films, Inc. is the acorn from which the new United Artists grew. The key concept is simple: it is not necessary, and not particularly desirable, to own a film studio – real estate, sound stages, equipment, payroll week in and week out, union hassles, taxes, maintenance, the lot – in order to be a major motion picture company. The necessities are: a suite of offices; a line of bank credit; skilled executives; and a distribution network. Having trialed and refined this system at Eagle-Lion from 1946 on, Arthur Krim shifted to the moribund United Artists in 1950 in perhaps the most successful management takeover in Hollywood history. (in 1951, Eagle-Lion ceased production; its product was taken over by United Artists). With no expensive filmmaking facilities, United Artists had virtually no overhead costs. They formed partnerships with producers in which United Artists would fund films fully or partially, and distribute the them (the guarantee of a distribution deal increasingly became a mechanism for attracting further funding if United Artists had only partially funded). The physical production and post-production of their films was done in rented facilities with rented equipment and personnel hired for the one-off production. The restructuring of United Artists around this business plan coincided perfectly with the divestiture decree. In competition with the old, physical plant studios, the company’s interests lay in encouraging independent production companies; its assets and strengths were its access to capital, its distribution expertise and the judgment of its executives. United Artists quickly became large enough to serve simply as a distributor for other, smaller independent producers – Allied Artists, Associates and Aldrich, and many others [3] Through the 1950s, United Artists produced around fifty films each year. [4]

The new ballgame.

At the end of the 1940s , national network television established itself in the U.S. and began a shifting, symbiotic, and often uneasy relation with the theatrical film industry and the re-structured studio system – television become another potential market for independent production companies. At first, the major studios response to the new medium was to recycle their archives through it as syndicated packages; then, as the double-bill dwindled as an exhibition format, the studios began to redirect their B-picture units toward providing new film product for the networks, often in close partnership [5] . At the same time, talent once under longterm contract to studios – stars, writers, directors, producers – decided not to continue their contracts and began to negotiate as free agents. To facilitate this, many set up their own production companies. This institutionalized their independent negotiating power and gave them more control over their projects and careers; it also gave them a cut of the producers’ share of box office earnings [6] . Some of these personal companies functioned as full-fledged production companies, initiating projects; [7] at the other end of the spectrum, some were concessions by the studios to powerful above-the-line talent who wanted a larger share in decision-making and profit-taking.

Opportunities, strategies, limits: indicative cases

These post-Welles filmmakers clearly wanted to make films on their own terms; sooner or later, all of them were elevated by critics to prominent places in the postwar directorial pantheon. It is useful to trace the various strategies of Aldrich and his colleagues as they negotiated the new production environment. This gives a concrete survey of options and career paths available to Aldrich. Ida Lupino, who had been in the Hollywood system since 1933 as an actress, then as a star, reversed Aldrich’s move from television to feature films. She first directed (uncredited) Not Wanted (USA 1949), an Emerald Production released through Film Classics. The same year, she and husband-producer Collier Young formed The Filmakers production company, for which she directed Never Fear (USA 1949), released by Eagle-Lion; Outrage (USA, 1950), released by RKO, as were her following films: Hard, Fast and Beautiful(USA 1951); Beware My Lovely (uncredited; USA 1952); Hitch-Hiker(USA 1953); and The Bigamist(USA 1953); all clearly marked by Lupino’s stylistic and thematic concerns. In 1952, she became one of the four stars in Dick Powell’s Four Star Playhouse (for which Aldrich directed while establishing his credentials). In 1954, The Filmakers hired Don Siegel to direct Lupino in Private Hell 36; in 1955, she starred in Aldrich’s The Big Knife(USA). In 1956, she abandoned her feature film acting and directing career to specialize in television directing, continuing to experiment with the possibilities of the medium [8] .

Anthony Mann worked in live theatre through the 1930s; in 1939 he joined Paramount as an assistant director (for Preston Sturges, among others) where he directed his first film in 1942. A journeyman director in the war years, he worked at Universal, RKO, and the minor studio, Republic. In 1947, he began a remarkable association with Eagle-Lion, directing or co-directing a series of cutting-edge black-and-white B noirs(often in company with the cinematographer John Alton): Railroaded (USA 1947); T-Men (USA 1947); Raw Deal(USA 1947); He Walked by Night (USA 1948); and Reign of Terror(USA 1949). He then did five studio films for MGM. With Winchester ’73, he became nouveau freelancer James Stewart’s [9] preferred director at Universal for a decade. During that period, he made two independent productions for Security Pictures, released through United Artists: Men in War (USA 1957) and God’s Little Acre (1958), both starring Robert Ryan. He ended his career directing blockbuster international co-productions assembled by Samuel Bronston. Apparently, with the exception of his two Security Pictures films, he wasn’t involved in independent production companies or television.

Don Siegel joined Warner Brothers’s editing department in 1934 as a film librarian. He spent his early years making montage sequences for features. He graduated to second-unit work, then made award-winning shorts during the war years. In 1946 and 1949, he made his first two features, for Warner Brothers. From 1949-1953, he worked mainly at RKO. From 1954-1956, he made four films for Allied Artists (released through United Artists) and one for Ida Lupino’s The Filmakers before settling for a long period with Universal and Eastwood’s Malpaso company. Along the way, Siegel made several forays into television, first with The Doctor(The Visitor in syndication, USA 1952-53), on which he alternated with house director (and production manager, and assistant director) Robert Aldrich. For television, Siegel not only directed series episodes; he also directed pilots and created series. His The Killers (USA 1964) was scheduled to be an early if not the first feature produced for television but instead was released theatrically in the aftermath of the assassination of president Kennedy.

Budd Boetticher’s Mexican bullfighting training brought him to Hollywood as a technical advisor on Blood and Sand (USA 1942). He stayed on as a messenger boy at Hal Roach Studios, then became an assistant director at Columbia in 1943. From 1944-1945, he directed five features at Columbia. He entered the independent field in 1948 (Assigned to Danger, USA 1948, Eagle-Lion) and followed up with two films at Monogram, one at Republic, and one at Hal Roach. From 1951-1955, he was a contract director at Universal. In 1955, he did A Killer is Loose (USA) for United Artists. He spent the rest of his career as house director for the Randolph Scott-Harry Joe Brown-Burt Kennedy cycle of art westerns, first for Batjac, released through Warners (Seven Men from Now, USA 1956); then for Scott-Brown productions, released through Columbia (The tall T, USA 1957; Decision at Sundown, USA 1957; Buchanan Rides Alone, USA 1958), and finally for Ranown (a new face for Scott-Brown) released through Columbia again (Ride Lonesome, USA 1959; Comanche Station, USA 1960). Clearly, what ended as Ranown was closely associated with the studio; if not as an in-house unit, then engaged in a close symbiotic relationship. During this period, Boetticher himself had no personal production company. He did television work, including for Dick Powell’s The Dick Powell Show (USA 1961-1963).

Producer-writer-director Samuel Fuller remained the most marginal of this group. Freelance story sales and occasional screenwriting in the 1930s were interrupted by WWII combat service (which would greatly influence his subsequent work). From 1949-1950, he released his first three features through Deputy Corporation/Lippert Productions (Lippert was an exhibitor turned exploitation producer). Fixed Bayonets(USA 1951) began an association with Twentieth Century-Fox which continued through 1957 (Forty Guns, USA). Interspersed was a Samuel Fuller Productions film, Park Row, released through United Artists (a personal film in which he invested US$200,000 [10] ) and the first of his Globe Enterprises Productions, Run of the Arrow (USA 1956). His Globe Enterprises productions would continue until 1960, when he landed a (relatively) well-budgetted Warner Brothers film, Merrill’s Marauders (USA 1961). In 1963, he did two poverty row independents of great style and structure for Fromkiss-Firks, released through Allied Artists. Much later, Fuller directed The Big Red One, USA 1980, for Lorimar and its German investors. (Lorimar had established itself as a television production company in the US with series such as The Waltons,1972-1981, before tapping international capital to branch into feature production. Lorimar produced Aldrich’s Twilight’s Last Gleaming, USA 1977, and The Choirboys, USA 1977). Following this, Fuller shifted to independent productions in Europe.

Unlike Lupino, Mann, Boetticher, Siegel, and Fuller, Joseph Losey and Nicholas Ray did not serve studio apprenticeships. Both had begun their careers in the 1930s in the world of left-wing and experimental theatre (Losey had a long friendship with Brecht). Both began directing at RKO. Losey was sponsored by the head of production, Dore Schary for his debut, The Boy with Green Hair (USA 1949). He then made The Lawless(USA 1950) for Pine-Thomas Productions, an in-house B-picture unit at Paramount. In 1951, he made three films for three different companies: The Prowler (USA 1951) for Horizon Pictures, released through United Artists; M (USA 1951) in-house at Columbia; and The Big Night(USA 1951) for Philip Waxman Productions, again through United Artists. A victim of the blacklist, he then shifted his activities to the independent sector of the British film industry.

Nicholas Ray had known producer John Houseman during his time in the New York theatrical world; when Houseman became a powerful producer at RKO, he sponsored Ray’s first films , beginning with They Live by Night (USA 1948). Of Ray’s first ten films (1948-1952), eight were made at RKO; the other two were Santana productions released through Columbia (Santana, Humphrey Bogart’s personal production company, had a multi-picture deal with Columbia). This productive stability vanished when he left RKO; with the exception of two back-to-back films for Twentieth Century-Fox in 1956-1957, he wandered through one-shot deals until, like

Mann, he became part of Samuel Bronston’s blockbuster industry in 1961.

The patterns emerging from these histories feature an unstable production and career environment in the wake of industrial restructuring. Recurring elements in these careers are working at or releasing through RKO; United Artists; Allied Artists; directing for independent production companies; and working in television. The older, established studios responded to United Artists’s challenge by adopting its game plan: reducing in-house production; establishing various sorts of partnerships with the proliferating independent production companies; they also set up television production wings. Of the majors, Universal was the first to reposition itself as a rental facility, a move soon followed by the other studios. By the end of the 1960s, it had become common industry practice for studios to bid against each other to provide production services to independent producers, usually for a fee of about 25% of a film’s production budget.

Associates and Aldrich: one man’s family

Aldrich’s response to this unstable environment was to establish an enduring repertory company of on- and off-camera colleagues, easily surpassing such earlier companies as those enjoyed by John Ford and Preston Sturges. His first film, 1953, and his last, 1981, feature the actor Richard Jaeckel, as do many of the films in between. His second film, the Monogram release World for Ransom (USA 1954), is a feature version of his television series, The Affairs of China Smith (USA 1952-53); the series star, Dan Duryea, transferred to the film, and would work with Aldrich again throughout his career. For this eleven-day shoot, Aldrich established the core of his continuing company: cinematographer Joseph Biroc, composer Frank DeVol, editor Michael Luciano, art director William Glasgow, and others. DeVol and Biroc shot and composed …All the Marbles(USA 1981), Aldrich’s last film. From Vera Cruz through the rest of his career, the director frequently cast Ernest Borgnine, the actor who most resembles Aldrich himself.

The advantages for Aldrich in the repertory arrangement were efficiency, familiarity, comfort, control, a tribal defence against corporate authority, and, one may suspect, a complex, mutually-advantageous paternalism. A representative list of company members, let alone a comprehensive one, is beyond this essay’s scope; interested readers should sit down with a good filmography and sort through it. [11] Aldrich’s third and fourth films (Apache and Vera Cruz) were produced by Hecht-Lancaster, Burt Lancaster’s production company, and released through United Artists. Apache cost US$1.24 million and grossed US$6 million; Vera Cruz cost US$1.7 million and returned US$11 million; [12] the gross returns on investment are 500% and 650% respectively, all the more impressive for independent productions with no continuing studio overhead costs. These returns put the films in Variety‘s annual list of top grossers; so Aldrich resumed the relationship he had begun with United Artists as an assistant director – but on more equal terms. Aldrich brought in his next film United Artists film, Kiss Me Deadly (USA 1955) on budget, and used its modest profitability as further leverage to formally establish his own company, Associates and Aldrich, to produce The Big Knife (USA 1955) for release through United Artists. The majority of his subsequent twenty-five films would be made through Associates and Aldrich.

Key images

For the next twenty-six years, Associates and Aldrich would survive and sometimes prosper in the new independent production environment. But frustratingly for Aldrich, never independent enough: the new hybrid production system was deeply symbiotic. The newly configured studios relied on the independents for product; the independents relied on the studios for funding, production facilities, and distribution; and everyone was reliant on a few specialized merchant banks. In 1967, Aldrich’s pre-Jaws (USA 1975) mega-hit, The dirty dozen (USA) broke all previous records and grossed $US eight million in its first week. The windfall profits allowed him to buy his own film studio (as Francis Ford Coppola would five years later). And also as Coppola, Aldrich used his studio to sponsor projects for himself and others which couldn’t find funding elsewhere, and the studio went broke. Aldrich moved to the flat coastal truckfarming community of Oxnard, one hundred kilometres north of Los Angeles, where he claimed to see all the films he watched with the locals in the smalltown moviehouse.

Necktie

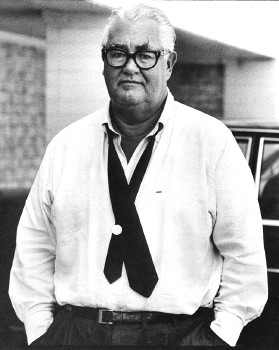

The image at the beginning of this article is a typical one. About half the pictures of Aldrich show him in no necktie. A few show him with a properly knotted tie. All the rest are like this, the necktie under his unfastened collar, not knotted at all, crossed over the apex of his paunch, and secured, usually with a paperclip, sometimes a tie clip. It is an in-between image, one which makes the wearing of the necktie its own critique, its own protest. It is a sign for Aldrich’s own in-betweenness: locked in a continuing struggle with the studios and the bosses, frequently presenting them as his antagonists (and vice versa), yet desperate to have his own studio and be a studio boss.

The kick and the punch

Aldrich understood, as did his fellow independent Otto Preminger [13] , the value of publicity, image, and profile. Preminger and Aldrich were prodigious interview-givers; they cannily manipulated the new auteurist climate to present themselves as the filmmaker-hero. Both men constructed larger-than-life public personae for themselves into which they fitted their film projects: both politically liberal and anti-censorship, Preminger took the high end of the market with large, serious subjects and a cerebral mien (Exodus, USA 1960, for example). Aldrich took the other end, often the lower end, never underestimating the market value of sex and violence (Preminger was never a comfortable action director). The second type of images of Aldrich is located here, among the many publicity photos of him on set or on location, very physically showing his actors exactly how he wants them to kick and punch each other.

Ten thousand pin-ups

A third Aldrich image shows him perched on a stepladder before a huge, high wall. The wall is papered with eight-by-ten glossie photographs of actresses. The accompanying caption tells us Aldrich is searching among the photos to cast the female star of his next film, Attack! (USA 1956). This image of remakable duplication and excess stands for Aldrich’s relation to women (contradictory, conflicted, often misogynist) because Attack! is a type of film Aldrich returns to often throughout his career: the all-male cast–or so nearly so as not to matter (see Brad Stevens’s parallel story regarding Flight of the Phoenix, USA 1966, elsewhere in this issue).

No comma

This image is not of Aldrich. It relates to the frequent claim that in making Kiss me deadly, Aldrich and Bezzerides “…took the title and threw the book away.” [14] It is an image–or a pair of images: the cover of Mickey Spillane’s novel Kiss Me, Deadly and the title of Robert Aldrich’s film version, Kiss Me Deadly on the credits, on posters, in print. Somewhere between Victor Saville’s purchase of the rights and the Aldrich-Bezzerides screenplay, the title lost its comma. The book title seems to be a request directed to someone deadly and so has delicate ambiguities (if we can use the word “delicate” in relation to Spillane): why would the speaker want someone deadly to kiss him? Aldrich’s comma-less version fits the film much better because it comes from his propensity for ferocity and brutality: the speaker asks the kisser to make the kiss a deadly one.

Lean

This image of Aldrich is a literary one and is here for its humor. Claude Chabrol wrote of Aldrich “His films resembled him: lean, extrovert, punchy, framed in concrete and edited with a trowel.” [15] It is just possible that Chabrol thinks Aldrich is actually (as opposed to metaphorically) lean, but one would have to have Chabrol’s build to begin thinking it.

A storm of bullets

When preparing his anti-war film Attack!, Aldrich approached the US Army for its cooperation, as was the practice of the time (Aldrich needed, among other things, a Sherman tank). Unusually, the Army refused because of an image in the film. The image showed American troops quite deliberately shooting their officer. And worse: shooting him for very good reasons. The last line of The dirty dozen is: “Shooting officers could get to be a habit with me.” Aldrich’s instinctive relation to authority is always with the sergeants, not the officers.

The moment

Whether a single image or a combination of images, there is a moment – usually fairly early in an Aldrich film – which drastically changes the paradigm and ups the ante. In Ulzana’s Raid (USA 1972, a recasting of his earlier Apache; both films star Burt Lancaster, blindingly young in the first, shrewdly old in the second), white settlers are being gathered into the fort for protection from Apache raiders. A woman drives a wagon with her little boy; a single mounted trooper accompanies them. Hostile Indians appear. A flurry of tense close-ups of all concerned, finishing with the frightened woman, then the young trooper. He draws his pistol and fires. Aldrich cuts to show he has shot the farmwoman between the eyes. The situation deteriorates. The trooper puts the pistol in his mouth and blows the back of his head off. The next sequence begins with a familiar image, the leader reconnoitering behind a ridge, surveying the terrain with his Army-issue field glasses. It is the leader of the Apaches. It is Aldrich’s signal that we are in a different kind of western now; but then, each of his six westerns has been unusual, non-standard (as have his six war films).

Nuke ’em

My key for understanding this aspect of Aldrich came while watching his surprisingly underdiscussed Twilight’s Last Gleaming (USA 1977), a title ironically snatched from an American patriotic anthem. A disillusioned Air Force general (Burt Lancaster again) has taken over a nuclear missile underground silo and is using it to force the government and the President to make public secret documents detailing the government’s covert crimes in the Vietnam war. The rebel general is in negotiation with the President and is threatening to send up the missiles. A guarantee has been given that no troops will be deployed against the general, but that promise is broken. When Lancaster sees troops approaching, he says (more or less) that’s it: they screwed me, now it’s their turn. In all the synergy Aldrich can muster with two-and four-panel split-screen work, Lancaster does it: he presses the button. We watch the missiles slowly rise from the siloes. At this point, I am simultaneously and equally registering, feeling, two contradictory things: No, no, you can’t do that, that’s what we’ve been afraid of since we had bomb drills in primary school, you can’t send up the atom bombs and kill people. And the other half of me, equally strongly, at the same time saying: Yes, give it to the treacherous bastards, they deserve it.

The ability to evoke such responses is what Robert Aldrich, independent, has finally been marketing all these years. For me, it is the center of Robert Aldrich. And he knows it’s the center of me.

Footnotes:

[1] Joseph Losey quoted in Tom Milne, Losey on Losey (Garden City: Doubleday, 1968):79.

[2] The resulting changes to production infrastructure and practices have parallels a decade later with the French nouvelle vague – and resulted in a similar rapid expansion of opportunities for beginning directors.

[3] See Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company that Changed the Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987). For Eagle-Lion, see his chapter “Prelude at Eagle-Lion”, 9-39.

[4] Anthony Slide, The American Film Industry, A Historical Dictionary (New York: Limelight, 1990):359.

[5] For an extended discussion of this area, see Christopher Anderson, Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994).

[6] Above the line (creative) and below the line (technical and support) talent receive salaries or fees paid out of the production budget. All others participate in the proceeds of the film’s exhibition. Some may be entitled to a share (percentage, points) of the net profit, after all costs and disbursements have been made; but studio accountants are at least as creative as other members of the community, and those waiting for their share of the net may wait a very long time indeed. Producers and production companies, and those with a share of the gross (rather than net) returns get their money just after the exhibitors and distributors, a much more desirable arrangement.

[7] Examples here include John Wayne’s Batjac, Fritz Lang and Joan Bennett’s Diana Productions; Burt Lancaster’s HalBurt, then Hecht-Lancaster, then Hecht-Hill-Lancaster; Collier Young and Ida Lupino’s The Filmakers; and later, Clint Eastwood’s Malpaso.

[8] See William Donati, Ida Lupino, A Biography (Lexington: the University of Kentucky Press, 1996) and Annette Kuhn, ed. Queen of the Bs: Ida Lupino Behind the Camera(Trowbridge: Flicks Books, 1995)

[9] Stewart was one of the first postwar stars to turn his back on the longterm studio contract system and instead negotiate as a free agent, significantly just after the divestiture decrees weakened the power of the studios. Stewart’s rapidly copied strategy was to defer all or part of his normal salary against a percentage (“points”) of Winchester ’73’s profits, making him essentially a producer of the film rather than an employee.

[10] In discussing this film with me 1n 1976, Fuller said: “Young man, don’t ever make the mistake I made: never put your own money in a picture.” I have followed his advice.

[11] Alain Silver and James Ursini, What Ever Happened to Robert Aldrich? His Life and his Films, New York: Limelight, 1995, is good; Silver’s Robert Aldrich: A Guide to References and Resources, Boston: G.K.Hall, 1979, provides even more detailed filmographies.

[12] Silver and Ursini, 11, 12, 14.

[13] Preminger’s brother, the literary agent Ingo Preminger, was a founding partner in Associates and Aldrich.

[14] Silver and Ursini, 12.

[15] Claude Chabrol, “B.A., or a dialectic of survival” in John Boorman and Walter Donohue, eds. Projections 4 1/2 (London: Faber and Faber, 1995):38.