G arborg’s novels are profound and gripping while his essays are clear and insightful. He was never inclined to steer clear of controversy. His work tackled the issues of the day, including the relevance of religion in modern times, the conflicts between national and European identity, and the ability of the common people to actually participate in political processes and decisions. Although he was to become known as an author, it was as a newspaperman that he got his start. In 1872 he established the newspaper Tvedestrandsposten, and in 1877 the Fedraheimen, where he served as managing editor until 1892. In the 1880s he was also a journalist for the Dagbladet in Oslo.”

I f you are about to perform a ‘miniature’—or any piece, really—it’s good to first take a moment and re-tell yourself a story that, to you, the piece embodies. “Write it down and clip it onto the sheet music,” my piano teacher told me when I was 8. “If the composer didn’t say what story the music is telling, then you need to make up a story. Or else how are you going to know what you’re going to say, or how you’re going to say it?” Five decades later, I continue to think that that’s a great idea. If a story wasn’t supplied by the composer, then you need to make one up. Make one up, write it down, remind yourself of it each time, right before you begin playing the piece.

[50-sec clip, Tor Espe Aspaas & Per Kristian Skalstad, Johan Halvorsen, ‘Suite Mosaique, No. 4: Chant de Veslemøy’, 1.6MB MP3]

[50-sec clip, Tor Espe Aspaas & Per Kristian Skalstad, Johan Halvorsen, ‘Suite Mosaique, No. 4: Chant de Veslemøy’, 1.6MB MP3]

T or Aspaas and Per Skalstad are very good at telling stories. They must’ve had music teachers like Ruth Mapson of my own childhood.

V eslemøy—in morose, poignant, fateful F-sharp minor. Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata is in F-sharp minor... Also, Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 1... Scriabin’s Piano Concerto and his Piano Sonata No. 3, too. Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto No. 1 and Vieuxtemps’s Violin Concerto No. 2... Second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23... Reger’s and Tippett’s second string quartets; Shostakovich’s string quartet No. 7... Two of Chopin’s mazurkas, plus a nocturne... Last but not least, two preludes and fugues in J. S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier are in F-sharp minor. F-sharp minor carries a lot of ‘attitude’.

F -sharp minor, although it leads to great distress, nevertheless is more languid and ‘love-sick’ than lethal. Moreover, it has something abandoned, singular, and misanthropic about it.”B ut what about Veslemøy? What do we know about ‘Veslemøy’?

— Johann Mattheson, 1713.

I n Norwegian, it nominally means “little girl” ... a compound of ‘vesle’ = “little” and ‘møy’ = “girl”. But it’s way more than that. This name was used by Norwegian author Arne Garborg for the main character in his epic poem ‘Haugtussa’ [The Mountain; literally ‘heap of rocks’] (1895). Almost certainly this popular Neo-Romantic Garborg poem was the inspiration for Halvorsen when he wrote this Suite in 1898. But the idiomatic compound ‘veslemøy’ was a commonplace way before Garborg even. It connotes ‘fairy’ or ‘sylph’—mysterious; charming and beautiful but creepy; other-worldly.

T he poem is propelled by Garborg’s rural culture and infused with its values and lore. A number of supernatural beings—like the Draug, the Hulderpeople, and other characters from Norse mythology inhabit the epic. A ‘haugtussa’ is originally a female subterrestrial (a woman troglodyte of the Hulder race). But here the main character, beautiful young above-ground Veslemøy, is revealed to be a Hulder and a haugtussa. The 219-page poem is dark and foreboding; it is not for no reason that its sequel, published in 1900, was ‘I Helheim’ (In Hell). More than a stereotypical, ever-cheerful Norsk outlook :Ѣ Garborg was rendering Dante-like divina commedia, a long oblique rant against the church and what he felt were deleterious social effects of church dogma and pious blind eyes turned away from real problems in the world—poverty, starvation, indignity, suffering.

V eslemøy (also called Gislaug) is the youngest of three sisters, and lives with her elderly mother near Jæren in rural Norway, south of Boknafjorden and northwest of Dalane in the county of Rogaland. The oldest sister has died, we are not sure how, maybe from tuberculosis, and her other sister has fled some time ago from the countryside to the big city—by implication, that sister has become a prostitute, wild and estranged from her family. So Veslemoy and her old mother are alone.

T hey are dirt-poor and live as tenants on a farm; like characters in a fantastical Haldor Laxness novel, they are harassed to their wits’ end by the local land-owner.

V eslemøy has a precocious natural insight into people and situations. She is savant-like in her surprising confabulations, each story containing enough kernels of truth to have a devastating verisimilitude. Other kids (and adults, too) gather around her to hear her tell stories, or to pose riddles—a famous winter fireside pastime for us fun-loving Norwegians.

V eslemøy habitually makes up stories, stories upon stories. One night, her dead sister visits Veslemoy and tells her that she is endowed with the capacity for ‘second sight’, to be psychic, and to foretell what will happen. Veslemøy’s stories are not entirely her ‘own’, and Veslemøy’s compulsion to tell them is not necessarily hers to control. The sister’s revelation is a great burden to Veslemøy, but she has no choice but to accept it.

G arborg’s point seems to be that it is better to be a ‘seer’—better to be spiritually ‘awake’ in a Zen sort of way or the state of Bodhi awake-ness attained by the Indian spiritual teacher Gautama Buddha and his disciples—than to be stultified/mortified by the oppression of routine day-to-day life and the paternalistic rule of priests. From this point forward, visions haunt Veslemøy, and the netherworld spirits pursue her. She is narrowly avoids being abducted underground by the Hulders. She has also the ability to see what symbolic animal spirit each person around her has behind him or her.

V eslemøy experiences the problems of tweens in any age: crazy first love, almost gets engaged to the kid on the farm down the road. Instead, the foolish boy finagles marrying a rich girl, and the experience of being dumped unhinges Veslemøy. Veslemøy has to fight even harder with her inner demons, who abduct her into the mountains. There, she meets trolls—some who are decent souls and others of ill repute. She commiserates with them about their crappy fate as outcasts, and how they have been deprived of a life worth living. The Haugkall (mountain king) proposes to marry her, despite the outrageous difference in their ages. She tells him No, Hell No [Well, actually she collapses because she sees that he has the mouth of a rat.] and is brought home sick and delirious. At the end of the poem, the dead sister consoles her again, and admonishes her to buck up and to get ready descend into Hell, accompanied by a volve/voluspa/goddess/wizard/witch/wolfwoman who will teach her “through horror, the work which will become your honor”.

H er ser du Visdoms Volve staa.

Ho vil deg gjeva djupt aa sjaa

og store Røynslur herde.

Ho bèr deg gjennom Helheims Gov;

der skal du skimte Livsens Lov

og gjennom Rædsle lære

det Verk, som vert di Ære.

[Here before you Wisdom—Volve—stands.

She gives you depth of seeing

and lets you hear what big Røynslur hears.

She compels you to go to Hell

where you can’t help but glimpse the Law of All Life

and from Horrors-more-than-Faith learn

that work which must be(come) your Fate-Honor.]

— Arne Garborg, ‘Haugtussa’, 1895.

S o Halvorsen didn’t need to write any story or provide program notes or annotations to his music; the notions above would’ve been familiar (from Garborg’s Haugtussa 1895 poem, or from Grieg’s Haugtussa lieder from the same year) to any Scandinavian who would’ve heard Halvorsen’s violin-piano duo in 1898 or the years shortly after.

B ut we need to write the story down and remember it, to make these few notes mean something. For us, Halvorsen’s chamber music—much of it, except, say, for the Passacaglia and Sarabande Duos for violin and viola—might seem sentimental or dated, hence, dismissible, if we don’t bother to find out about what motivated the composer to write it. We need to invest a little energy to find out why it mattered at the time—what the social context was, who the performers and early audiences for the works were, and what they cared about—in order to accurately value the works. In the case of Halvorsen, Aspaas and Skalstad do a wonderful job of reanimating these pieces, entering into them, and reminding us of the characters’ stories—and how being ‘awake’ and engaged matters in present-day society. Fear and absurd suffering as the ‘juice’ for creating meaning and redeeming humankind; theodicy; the eternal return; Neo/TheOne; an 1895 feminist ‘Matrix’, sort of.

S o Halvorsen’s violin-piano duos are nothing like Stravinsky, Elgar, Elliot Carter—any of the works that fill the 110 pages of ‘violin-piano’ repertoire in Hinson’s book. We have wonderful violin double-stopped consonance flavored by piano dissonance. We have haunting, brooding, poignant, elegant, serious recital behavior, not encore bon bons. We have exalting, transcendent phrasing if you are careful and listen for it. The pieces are short. If you blink, you’ll miss it.

B rahms tries to make the violin and piano co-equals; Schumann instead often pitches the violin as a virtuosic protagonist against the piano. But those are ‘big’ works. The small scope and small timescale of miniatures like Halvorsen’s don’t allow for that kind of dramatic development. Instead, we have these mystical, Neo-Romantic microfictions.

T he uneven weight between the bowed and hammered strings does not have time to sink-in or become problematical. The piano roams free in the middle and treble registers, just as a microfiction character would. Listeners’/readers’ minds are obliged to interpolate, to read between the lines. Microfiction will not support any expectation of explicit storytelling. It is all between the lines. It must be so. There are too few lines for it to be otherwise. So, with microfiction (i.e., miniatures like Halvorsen’s), we understand its ground-rules before we begin, and we relish the extra interpretive responsibility that the author/composer places on us.

Y ou might think that miniatures would be ideal for our time—an era of short attention-spans and a taste for sound-bites and web-surfing. But no. The small size actually requires patience and effort.

T he replication 8-8 | 8-8 in this 32-bar piece provides a natural suggestion of reconsideration. Not ‘repetition’ but something more like... like... like Faulkner’s ‘As I Lay Dying’ where different chapters are told from the point of view of different characters, whose personalities change as the story proceeds. Veslemøy above ground starts with a downbow, with the mute on (piano-violin duo, with the mute on!), and the Veslemøy underground, bowing inverted now begins with upbow. The violin before, and the violin after. Piano, trans-substantiated; shape-shifting piano. The repetition/reconsideration/return (with the upbow/downbow inversion effects and with properly calibrated subterranean piano pedaling) provides us a chance to get inside each character’s mind and discover each character’s uncertainties—about what is real and what is illusion; about who one is and who one was/will be. Fiction? Hardly!

W e find that each character is receptive to all types of detail. Poetics are found in merely taking a drink of water; magic is found in merely talking to the wolf. Don’t ignore the wolf or pretend like it’s not there. You’d better talk to it.

I f this stuff interests you, please have a look at Kristin Rygg’s nice chapter in Ulla-Britta Lagerroth and Erik Hedling’s book (link below). Clairvoyance, mystical duties, the obligation to give voice to songs not yet born, the symbolic meanings of upbow and downbow.

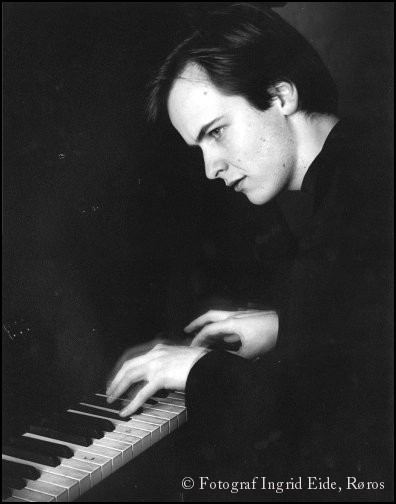

T or Aspaas was born in 1971 in Røros. Aspaas received his Diploma in Piano Performance in 1996, studying with Liv Glaser and Jens Harald Bratlie. Since 2007 he has served as professor of piano on the faculty of the Academy in Oslo. He is particularly active and sought after as a chamber musician; ensemble performance and accompaniment are also his specialties at the Academy. Besides his concertizing and teaching activities, Aspaas has served as artistic director for the chamber music festival Vinterfestspill in Bergstaden on Røros since 1999.

P er Skalstad was born in 1972. At age 12, he entered the Norwegian State Academy of Music (NSAM) in Oslo, pursuing both piano and violin. Skalstad got his Diploma of Violin Performance in 1995, studying with Stig Nilsson, Lars Anders Tomter and Camilla Wicks. In 2002, he completed his Diploma of Conducting, also at NSAM. In 1988 Skalstad joined the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra. With the NCO, Skalstad plays the viola when needed. Per founded the Oslo String Quartet in 1991, with Geir Inge Lotsberg (viola), Åre Sandbakken and Øystein Sonstad (cello). Skalstad was assistant concertmaster in the Norwegian Opera Orchestra from 1993 to 2005, and he has performed as a soloist with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra, the Bergen Philharmonic, the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra and the Risør Festival Strings. In the 2004 Halvorsen recording with Aspaas, Skalstad played on the Halvorsen`s 1705 Rogeri.

- Johan Halvorsen Chamber Music

- 6 Stimmungsbilder for Violin and Piano (1890)

- Suite in G Minor for Violin and Piano (1890)

- Danses norvégiennes for Violin and Piano (1897)

- Elegie for Violin and Piano (1897)

- Passacaglia in G Minor on the Theme by Georg Friedrich Händel (from Harpsichord Suite in G minor, HWV 432) for Violin and Viola (1897)

- Sarabande con Variazioni in G Minor on the Theme by Georg Friedrich Händel for Violin and Viola (1897)

- Crépuscule for Violin and Piano (1898)

- Suite Mosaïque for Violin and Piano (1898)

- String Quartet in E, Op.10 (1901)

- Little Dance Suite for Violin and Piano, Op.22 (1902)

- Slåtter for Violin Solo (1903)

- Miniatures, 5 Easy Pieces for 2 Violins and Piano, Op.29 (1910)

- To serenader for Violin and Piano

- Norske viser og danse for Violin and Piano

- Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies for 2 Violins

J ust knowing the dream, just knowing the song,

the tune will hold fast in your mem’ry—

seductively beckoning the whole day long.”

— Arne Garborg, ‘Haugtussa’, 1895.

- Tor Espen Aspaas website

- Per Kristian Skalstad website

- Oslo String Quartet website

- Johan Halvorsen page at Wikipedia

- Johan Halvorsen, Suite Mosaique score at IMSLP

- Aspaas T, Skalstad P. Johan Halvorsen Violin-Piano Duos. (2L, 2004.)

- Daverio J. Crossing Paths. Oxford Univ, 2008.

- Faulkner W. As I Lay Dying. Modern Library, 2000.

- Hinson M, Roberts W, eds. The Piano in Chamber Ensemble: An Annotated Guide. 2e. Indiana Univ, 2006. (section on Duos for Violin & Piano, pp. 3-119, omits Halvorsen)

- Hinson M. Essential Keyboard Repertoire, Vol. 8 (Miniatures). Alfred, 2006.

- Loft A. Violin and Keyboard: The Duo Repertoire: Volume II: From Beethoven to Today (1970). 3e. Hal Leonard, 2003.

- Neuhaus R. As I Lay Dying: Meditations Upon Returning. Basic, 2003.

- Rygg K. Mystification through musicalization & Demystification through music: The case of Haugtussa. in Cultural Functions of Intermedial Exploration. E. Hedling & U-B Lagerroth, eds. Rodopi, 2002. pp. 87-102.

- Veslemøy Vråskar, photographer in Olso

No comments:

Post a Comment